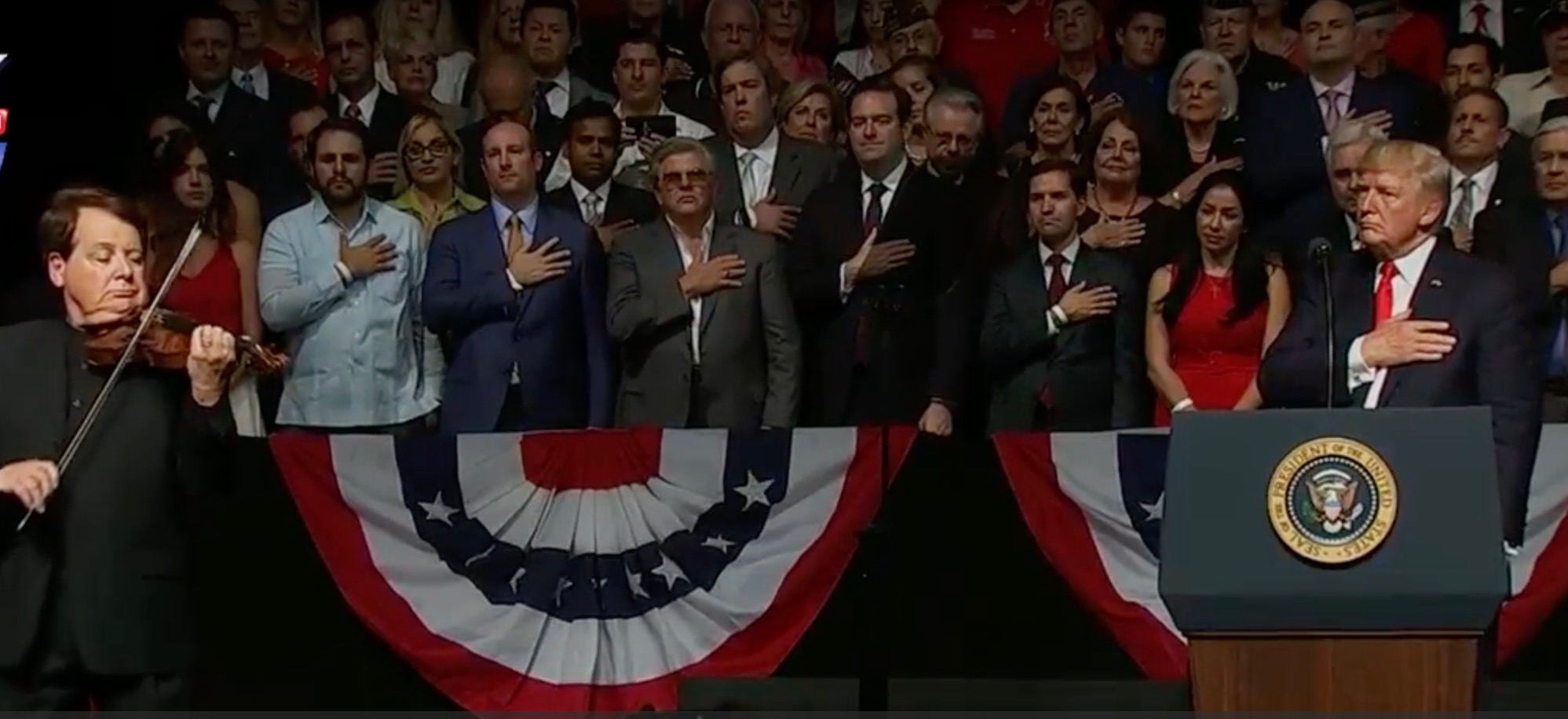

Donald Trump in Miami

HAVANA — Once again, a U.S. president shows up in Miami to promise the fall of the Cuban regime.

For half a century, this has happened for different causes and purposes: to appear tough on communism during the Cold War, to secure the vote of the Cuban-American community or, like now, to buy the collaboration of a couple of Congressmen against the threats arising everywhere against the Donald Trump administration.

The difference this time is that rhetoric will no longer ensure the Cuban-American vote, the Cold War ended long ago, and the support of those Congressmen could be extremely toxic.

Trump’s speech was old, as old as the “historic exile” that worshipped his sick megalomania. More than one commentator described it as a grotesque act and others called it cynical. The organizers were so clumsy that they forgot to place a Cuban flag on the stage and the national anthem that was heard was that of the United States.

According to The New York Times, the best thing about the announced policy was that it’s not as bad as it could have been. I believe that it was as bad as circumstances permitted and, if it’s not worse, it’s because they were not capable of making it worse. That’s the essence of the scenario that we are living in, and what we must take into account to analyze the trend toward the future.

Although the adopted measures supposedly respond to the claims of the Cuban-American community, none of them affect the relations of that community with Cuba. The reason is that the Miami politicians know the cost of acting against this population’s majority will and have grown fearful, which indicates the decrepitude of a force that used to impose itself offhandedly.

Facing U.S. society and the rest of the world, it was unsustainable to break the re-established diplomatic relations or cancel the mutual-interest accords signed by the two countries. Not even Trump decided to affect the deals already established, and the limitations he imposed are limited to prohibiting any future accords with Cuban military enterprises.

The only substantive damage was to limit, once more, the right of Americans to travel to Cuba. The blockade forbids that they do so as tourists, but 12 categories have been established related to cultural and informational interests, and there are general licenses to travel under those conditions.

These categories hold, but the general license for the so-called “people-to-people” contacts was eliminated. Only group travel will be authorized, with a pre-established agenda, a responsible guide who will enforce the regulations, and auditing mechanisms that will force travelers to justify every expense in Cuba. Documentation must be kept for five years.

The objective is to limit the flow of American travelers to Cuba, a number that has doubled since Obama eliminated those very same restrictions at the end of his term.

It’s worthwhile analyzing the re-establishment of this measure to understand the philosophy that guides U.S. policy toward Cuba and the enormous contradictions it entails for the U.S. political discourse itself.

Cuba is the only country in the world to which Americans cannot travel with total freedom; this was prohibited in the days of Kennedy. Carter eliminated that prohibition but Reagan reimposed it and finally the Cuban-American Congressmen managed to introduce it as an appendix to the Helms-Burton Act, which granted legal standing to the blockade against Cuba.

This restriction runs counter to the theory that people-to-people contact is a channel for influence over Cuba, inasmuch as an encounter with Americans would lead Cubans to surrender to the fascination that U.S. society engenders. That’s what the Torricelli Law says, a bill passed to topple the Cuban regime. But evidently the Cuban-American rightwingers don’t believe that and have always tried to limit contact between the two countries.

Travel by Americans is one of the basic sources of growth for the Cuban private sector. Studies made in the U.S. indicate that most of those travelers stay at private homes, eat at private restaurants and use private means of transportation during their stays in Cuba.

There are several reasons to explain this preference. First, it’s more “chic.” Second, it’s cheaper. And finally, because — since tourism is not allowed — Americans cannot take advantage of the “all-inclusive” plans that are so prevalent in the Cuban hotel chains, especially those on the oceanfront.

To limit the travel of these people affects the very sector that the U.S. government and the Cuban-American rightists say they want to benefit, inasmuch as they consider it an ideal “agent” to change the Cuban regime.

The reality is that this is a lie. The Cuban-American right doesn’t want to benefit anyone in Cuba and does not advocate “gradual and peaceful transit.” It is betting on promoting chaos, so it can establish itself as a dominating force on the island, under the tutelage of the United States.

What happened in Miami is a step backward in the process toward the normalization of relations between the two countries, but it has been unable to alter its strategic sense and will not be a panacea for Donald Trump to defend this policy inside U.S. society and in the international arena.

Rather, it may help strengthen the struggle in Congress against the blockade and may backfire against the Cuban-American right in the 2018 Congressional elections.

It harms Cuba, because the island needs to maintain a civilized and mutually convenient relationship with the U.S., but the Miami “show” does not dramatically transform Cuba’s national scene or its relations with the rest of the world. Cuba’s priorities lie elsewhere.

If Trump’s speech served to do anything, it was to unite Cubans even more. I don’t know anyone who finds the fellow “simpático,” the majority felt that Miami politics cannot be the future of Cuba, and nobody any longer debates how to deal with U.S. policy, as happened with Obama.