Trump arraignment contrasts typical impunity for US leaders

By Jessica Corbett / Common Dreams

The historic arraignment of former U.S. President Donald Trump on Tuesday highlighted how infrequently American political leaders are held accountable for any crimes.

“The last time anything remotely similar happened was” in 1872, when a police officer arrested then-President Ulysses S. Grant for speeding in a two-horse carriage—an incident that only came to light in a 1908 interview,The New York Timesreported.

Trump, now a 2024 Republican presidential candidate, faces 34 felony counts for allegedly “falsifying New York business records in order to conceal damaging information and unlawful activity from American voters before and after the 2016 election.”

As Free Speech for People noted, the twice-impeached former president still has not faced legal consequences for alleged “crimes related to the January 6, 2021 insurrection and the events leading up to it; crimes related to Trump’s January 2, 2021 phone call demanding that the Georgia Secretary of State ‘find 11,780 votes’… the obstruction of justice crimes identified by Special Counsel Robert Mueller in the second part of his report; crimes identified by the inspector general of the Office of the Director of National Intelligence related to Trump’s attempts to extort Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelenskyy; and others.”

“Trump may be the first former president to face criminal prosecution, but that fact in and of itself is a damning condemnation of the U.S. system of impunity.”

Trump’s prosecution in New York “is a good first step,” according toThe Intercept‘s Jeremy Scahill, but it “is not evidence that our much-vaunted justice system can actually be applied fairly and evenly to all, even a former president.”

“Trump may be the first former president to face criminal prosecution, but that fact in and of itself is a damning condemnation of the U.S. system of impunity that has long permeated our system of American exceptionalism,” the journalist argued Tuesday.

“This case against Trump would be a mere footnote of history, albeit a wild one, if the U.S. actually believed in holding presidents and other top officials accountable for their crimes, including those committed in office.”

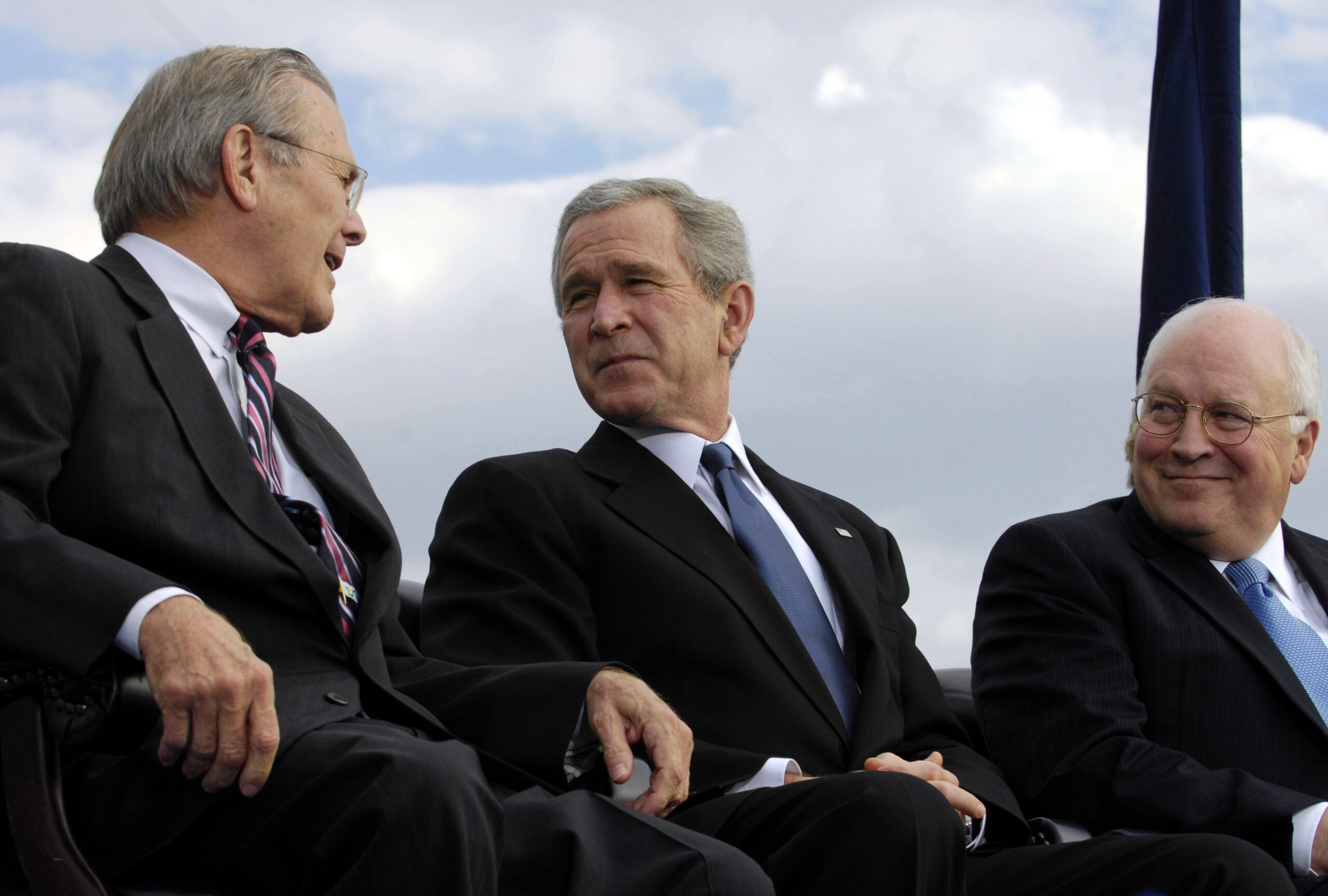

Pointing to former U.S. President George W. Bush; his vice president, Dick Cheney; and Henry Kissinger, who served as secretary of state and national security adviser in the Nixon and Ford administrations, he asserted, “The truth is that all of them should be serving substantial prison sentences for directing and orchestrating the gravest of criminal activity: war crimes.”

However, former U.S. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-Calif.) “steadfastly refused to even consider impeachment proceedings against Bush,” and former President Barack Obama made clear that “no one would be prosecuted for running a secret global kidnap and torture regime under Bush and Cheney,” Scahill wrote. “The system depends on such bipartisan impunity.”

The prosecution of Trump comes on the heels of the 20th anniversary of Bush’s illegal invasion of Iraq. Just ahead of that milestone last month, the U.S-based Center for Constitutional Rights (CCR) renewed its call for reparations and accountability.

“Reparations are rooted in precedent and international law, as well as a strong tradition of justice-based organizing by civil rights movements, and we should not let the difficulty of securing justice deter us from seeking it—for Iraqis and for all others harmed by U.S. imperialism, exploitation, and genocide,” CCR said. “Justice also entails accountability for the perpetrators of these horrific crimes, including those responsible for the torture at Abu Ghraib and other detention centers in Iraq.”

CCR further demanded justice for those tortured and detained in the broader war against terrorism that Bush declared in response to the September 11, 2001 attacks—while also acknowledging that “legal efforts against high-level political and military leaders for the invasion itself and the many crimes committed in the ‘war on terror’ pose a different set of challenges, as demonstrated by our efforts to hold high-level Bush administration officials accountable at the International Criminal Courtfor crimes in or arising out of the war in Afghanistan or under universal jurisdiction.”

The United States is notably not a party to the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (ICC), the treaty which established the Hague-based tribunal to investigate and prosecute people from around the world for genocide, war crimes, crimes against humanity, and the crime of aggression.

Nearly a year after 9/11, Bush signed into law the American Servicemembers’ Protection Act. Dubbed the “Hague Invasion Act” by critics, it empowers the president to use “all means necessary and appropriate to bring about the release” of any U.S. or allied person “who is being detained or imprisoned by, on behalf of, or at the request of the International Criminal Court.”

Last month, roughly a year into Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the ICC issued international arrest warrants for Russian President Vladimir Putin and Commissioner for Children’s Rights Maria Lvova-Belova for allegedly abducting Ukrainian children.

While Putin has “exhibited zero concern about his indictment,” his “invasion of Ukraine has created an interesting predicament for the U.S. empire on these matters,” Scahill highlighted, explaining that though President Joe Biden has called the Russian leader a war criminal, the United States has long “encouraged ad hoc tribunals” rather than supporting ICC prosecutions.

“The whole purpose of this from the U.S. perspective is to ensure that these laws will never be applied to Americans or their friends,” he wrote. “The prosecution of Trump should thus serve as a reminder that the U.S. does not actually believe in holding its most powerful citizens accountable for even the most serious of acts. And that position has real consequences, including in how it can be weaponized by criminals like Putin.”

“Make no mistake, Trump should be prosecuted for a variety of crimes, committed both as a private citizen and public official,” Scahill concluded. “But if we want to claim that our system is exceptional, then the same fate should be brought to bear on the Bushes, Cheneys, and Kissingers of the world as well.”