The historical controversy surrounding February 24 in western Cuba (Part 1+Español)

The Revolutionary Junta of Havana met on February 17, 1895, at Juan Gualberto Gómez’s home in Havana. The order for an uprise was read, and each attendee stated the number of men they had. The date was set for February 24.

***

The uprising for Cuban independence on February 24, 1895, on the western side of the Island was intended to occur in Ibarra, Matanzas, but it failed. What were the reasons for its failure, and what mysteries and questions remain unanswered about this key event in Cuban history?

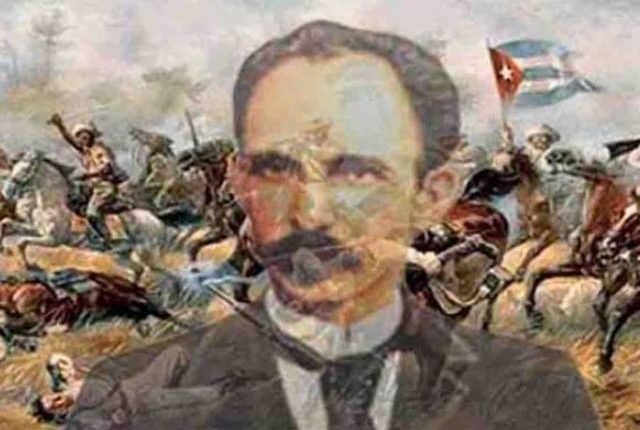

José Martí stated that Matanzas was “totally in agreement with the spirit and action of the other regions of the Island” and noted that its conspiratorial groups were “almost all led by doctors.” One such doctor was Dr. Pedro E. Betancourt Dávalos, a member of the generation that Martí referred to as “the new pines.”

The strategy and organization of the uprising![]()

Martí founded the Cuban Revolutionary Party (PRC) in Key West in June 1892. In August, his commissioner, Gerardo Castellanos, arrived in Matanzas. He met with more than 150 patriots and informed Martí “that everything had been done in Matanzas.” They formed the first Revolutionary Committee, with Emilio Domínguez as president and Pedro Betancourt as treasurer.

By 1894, the revolutionary leadership understood that the conditions existed for the start of the “necessary war” due to the coincidence of a favorable international situation, especially popular support in the United States, and favorable internal conditions on the island. The crisis of autonomism had weakened the internal barriers to the development of the revolution, and the island’s economic situation favored the independence movement due to the effects of the tariff war between Spain and the United States.

One decisive factor in the organizing process was coordinating all the conspiratorial nuclei within the island to create a coherent and effective force. By sending special commissioners, Martí proposed “laying the safe net of the Revolution across the island.”

Martí’s personal representative in Cuba was Juan Gualberto Gómez, a renowned conspirator and journalist. Like Pedro Betancourt, he was born in Sabanilla and four years older than him. In 1984, Martí appointed him PRC Delegate in the Western Department and named General Julio Sanguily, who had distinguished himself in the Great War, as military chief. Juan Gualberto became the intermediary between the leadership of the PRC and the conspiratorial groups and the most important disseminator of Martí’s ideology in the country.

Years later, Juan Gualberto recalled: “In 1894, there were such strong groups in all the provinces that it was believed possible to carry out the movement that year. The conspiracy followed an eminently decentralizing plan. In each province, half a dozen men took charge of the work, communicating directly with Martí and General Máximo Gómez, or through Juan Gualberto himself.”

The order for an uprising

The first problem with the military organization was that most leaders and officers from the War of 1868, even when eager to resume fighting, subordinated all action to the presence of an experienced and reputable military command. Among them were General Francisco Carrillo in Las Villas and Salvador Cisneros Betancourt in Camagüey. Only the authority of Máximo Gómez could unite these men under a single national strategy. In 1893 and 1894, Martí and Gómez devised a plan to initiate the “necessary war,” based on simultaneous armed uprisings across the island, supported by expeditions landing to bring together the principal military leaders from Oriente, Camagüey, and Las Villas.

According to Juan Gualberto Gómez: “Martí’s idea was that the Revolution should not be exported to Cuba by a group of Cuban emigrants; instead, it should arise from within the country, initiated by Cubans internally. The role of the emigrants would be limited to providing moral and material support and facilitating the arrival of esteemed leaders from the Great War.” Therefore, the opportune moment for the uprising would be determined by the conspirators in Cuba.

Towards the end of 1894, the conspirators in Havana and Matanzas were urging Martí. They believed that the conspiracy was at risk and that they could all be arrested, as it was known that the movement had been infiltrated by the Spanish authorities.

Betancourt, Emilio Domínguez, Marrero, and other Matanzas residents urged Juan Gualberto to set a date for the uprising. In January 1895, Julio Sanguily demanded that Martí give the immediate order for the uprising because he could not wait any longer. He warned that if Mart did not comply with his instructions, he would rise up alone.

The long-awaited authorization for the uprising, dated January 29 and signed by Martí, José María “Mayía” Rodríguez, representative of General Máximo Gómez, and Enrique Collazo, commissioner of the Revolutionary Board in Havana, reached Juan Gualberto Gómez at the beginning of February, concealed within a cigar brought from the United States. It authorized the uprising to take place in the second half of February and stipulated that at least three provinces must be willing to participate, with one being essential: Oriente.

La controversia histórica en torno al 24 de febrero en Occidente (primera parte + English)

This put Martí’s delegate in a difficult position: if the conditions were not fulfilled, he would have to suspend or postpone the uprising and give counter-orders to the provinces and groups already committed. What a responsibility!

The Revolutionary Board of Havana convened on February 17 at Juan Gualberto’s house. The order to rise up was read, and each attendee reported the number of men they had. Juan Gualberto continued, “And we looked at February 24… the 24th was a Sunday… and it was the first day of carnival; thus, it should not be surprising… that groups of people on horseback could form, that they could roam around, and even that someone would dress up.”

It was also agreed that the leaders would hide from the 20th to avoid arrest. “We had agreed that on the 20th, all of us who were at the head of the movement should disappear from our homes…” Unfortunately, this agreement could not be fulfilled.

In a letter he sent shortly after the failed uprising, Betancourt assured Juan Gualberto: “…in the penultimate interview we had… I was definitively charged with transmitting the order of said pronouncement to each of the group leaders in the province of Matanzas, in a timely manner, so that each one would go with his contingent to the designated place at the predetermined time and day. To ensure that each one received his notice in a timely fashion, I previously consulted each leader individually, so that on an agreed date for the uprising, he would have time to prepare and take his group to the meeting place… I was able to fulfill what was agreed upon with the strictest adherence to what was stipulated. Each group leader under my command knew, when he was supposed to know, the day, hour, and place designated for the uprising.”

Between February 18 and 23, Betancourt transmitted the order to all the group leaders. A decade later, veteran fighter Juan Gualberto Gómez remarked, “Not all of those committed to starting the patriotic work kept their word, nor did they all behave honestly; and among those who did, not everyone enjoyed the favor of fortune, and many perished in the conflict.”

The adhesion of General Carrillo: contradictory versions

At the meeting of the Revolutionary Board on February 17, Pedro Betancourt was tasked with meeting General Francisco Carrillo in Remedios, Las Villas, and delivering the order to rise up. He completed this mission on Friday, the 22nd. However, Carrillo responded that he had received instructions from Máximo Gómez not to rise up until he was in Cuba. As a result, the central province remained quiet on February 24, making it more difficult to sustain the revolution in Matanzas. Consequently, one of Martí’s conditions for the uprising was not met.

For this feat, Pérez Guzmán states, “Martí did not obtain the total support of significant groups of conspirators, such as those from Holguín, nor from key leaders of past conflicts like Francisco Carrillo.” Regarding the incorporation of Camagüey, he notes: “There were reports that the province was reluctant to be among the initiators of the conflict.”

Martí wrote to Juan Gualberto: “My personal opinion is that the West should never, ever, begin without prior coexistence with the East and a solid connection in Las Villas, whose advice you will necessarily have to request…” Carrillo’s refusal made Martí’s condition that at least three provinces join the uprising impossible to fulfill and forced Juan Gualberto to issue a counter-order to Matanzas and the East. Martí’s representative was unwilling to apply the brakes to the revolution.

To be continued…