Cuba nowhere to be found in Biden’s first 100 days

Last week before a joint session of the United States Congress, President Joe Biden gave an account of the first 100 days of his newly formed government. Since Franklin Delano Roosevelt managed to impose the fundamental measures of the New Deal in a similar time frame, the U.S. political norm is to calculate during a same period of time the course of each new administration and its possible success.

Biden has not fared badly when evaluating his results. According to a recent Gallup poll, 54 percent of Americans support his performance, a high number when compared to the 40 percent obtained by Donald Trump during his first 100 days. This result has been influenced by the perception that the pandemic is being better managed when viewed by the reduction of infections and deaths due to it, and thanks to the mass vaccination of the population. At the same time, there are signs of a certain economic recovery associated, especially, with the increase in job opportunities.

In contrast, as he concentrates on the enormous domestic problems that the United States traverses, Biden’s foreign policy appears to be lacking new initiatives. Although doctrinally speaking, great differences contrast the foreign policy of the current administration with that of Donald Trump’s — reflected in matters such as the official discourse, the attitude towards multilateralism, and the treatment of allies — in practice, there have been no changes of relevance.

Biden’s speech was a manifesto of high social content in keeping with the most orthodox traditions of democratic liberalism. This particularly pleased the so-called progressive sectors of the party, which indicates the importance reached by this sector in the Democratic Party ranks, facing the also monolithic Republican bloc that has already announced its opposition to the president’s plan. The issue, then, is not how ambitious the president’s proposals are, as the press has highlighted, but rather his ability to put them into practice in the complex North American political scenario.

His proposals include multi-million dollar relief plans to cure the pandemic’s economic effects, and large government investments in civil infrastructure, a typically Keynesian formula, which also has the political objective of fracturing the base of support that helped Trump win the presidency. These include billions of dollars guaranteeing free access to community universities, child care and improvements in the health care system. The plan is called the American Family Plan. It includes a call to tackle social problems such as social equity, systemic racism, women’s rights, the protection of the universal vote, gun control, care for the environment, and better treatment of immigrants.

The big question is where will the money come from. One answer lies in the magical reproduction of the dollar without base in the real economy, which implies that all citizens of the world, in one way or another, will pay to save the American economy. The other is by increasing taxes, for which reforms are proposed that would benefit the poor sectors and the middle class at the cost of increasing taxes on the very rich and corporations, which, although modest if approved, would have an economic and political value. In other words, the project we see unfolding is one to strengthen government’s influence on the national economy in stark contradiction with the conservative tendencies prevailing in the country.

And except for the immigration issue, more in concert with domestic politics where the Biden government is trying to reach agreements with Mexico and the northern triangle of Central America to stop the flow of immigrants at the border, the U.S. government’s foreign projection is limited to exhortations about the “return” of the United States to the international arena — as if it had ever left — and grandiloquent statements returning to the project of the “New American Century” which, incidentally, was an invention of the neoconservatives.

The discredited commitment to the promotion of democracy and the defense of human rights is being used as the pillar of a diplomacy in charge of restoring the ‘leadership’ role of the U.S. in the world. Subordinating foreign policy to “the interests of the North American middle class,” reminds us of Donald Trump’s chauvinist “America First,” albeit in more elegant words.

Yet, the international scenario remains the same. China is at the center of the hegemonic dispute and there remain sources of conflict with all countries that are not subordinate to U.S. policy. The military budget remains intact, which constitutes a huge burden for the proposed internal reforms, and sanctions continue to be the main source of US influence on an international scale. The Biden administration has not removed a single one of the sanctions imposed by Trump or his predecessors on dozens of countries on almost every continent, nor has it expressed an intention to modify this policy.

Cuba is one of the most illustrative examples of the subordination of foreign policy to the domestic interests of one party or another. This has been the case throughout history and the most recent example was the dismantling of Obama’s policy by Donald Trump in order to win the support of the Cuban-American extreme right in Miami. Biden promised to make amends if he won the presidency, but after one hundred days of his rule, we have not seen action on the matter.

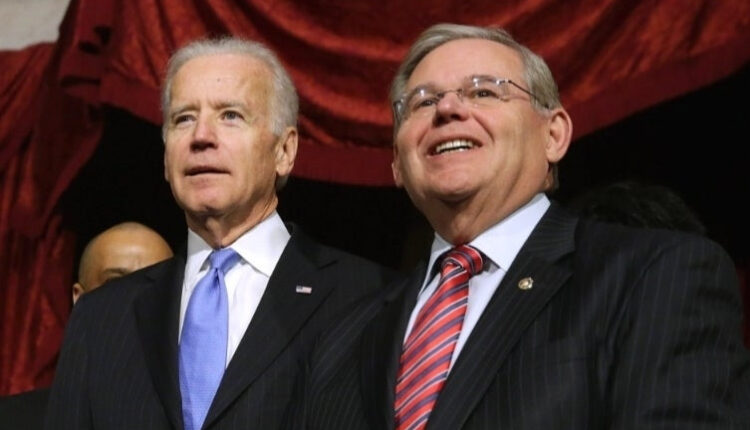

It is said that the silence regarding Cuba is part tactical to avoid conflicts in Congress, but in reality this is reduced to appeasing the anti-Cuban fanaticism of Senator Bob Menéndez. Cuban-American Republican members of Congress will never vote in favor of the Biden initiatives, no matter what they do with regard to Cuba, and a policy aimed at improving relations with the Island would be welcomed by the majority of Democratic Party members, and even by many Republicans who support this process.

For better or worse, Cuba cannot be spurned by the United States claiming it is not a priority. The Cuban market is an important one, even when supplementary, for many U.S. economic sectors. It is important for them that this space not be occupied by competitors, which explains the tremendous investment that persecuting and sanctioning the Island means; the sanctions themselves constitute a constant friction point with its allies; geographic proximity makes the Cuba issue one of national security for the United States; Cuba policy is an obligatory reference point for relations with the Third World and, indeed, impacts in many ways the internal dynamics of the U.S.

The real obstacle to advancing the improvement of relations with Cuba lies in the fears and ambivalences of some government officials. This is also a defining characteristic of American liberalism.