Speaking of dialogues

Coinciding with the debate regarding the need to promote dialogue among Cubans, the Ocean Sur publishing house just issued the book Cuba and its Emigration, 1978, Memories of the First Dialogue, a compilation by researcher Elier Ramírez Cañedo that contains documents, testimonies and analyses related to the so-called Dialogue with representative figures of the Cuban community abroad held at the end of 1978 in Havana.

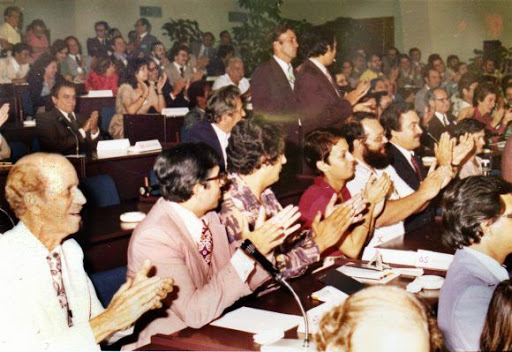

Attended by about 140 Cuban émigrés, mostly from the United States, it resulted in the establishment of a radical change in Cuban policy towards its emigration, as well as the promotion of a different treatment of this phenomenon within Cuban society with repercussions that continue to this day. It is worth analyzing the ideas and norms proposed by Fidel Castro, who led the Dialogue and was responsible for its conceptualization and implementation.

The call to meet surprised everyone. It seemed an impossible mission given the level of contradictions between the potential participants. Cuba’s emigration had served as the operative and social base of the U.S. plans against Cuba. For that reason emigrants were identified as traitors to the fatherland, and an absolute lack of communication existed between the sides. It was enough for a person to have relations with a relative who had left for his condition as a revolutionary to be discredited.

As expected, the first reaction of the majority of the Cuban people was to reject the meeting and its results, which included among its main agreements the authorization of visits to Cuba, suspended by Cuba and the United States for more than 20 years, as well as the liberation of 3,600 prisoners for counterrevolutionary crimes.

However, for Fidel Castro, “capturing the adversaries” constituted a doctrinal principle of the revolutionary strategy and he defended its application in this case as well. It was necessary to call for a meeting at the Karl Marx Theater on February 8, 1979, to explain the results of this congress to leaders and militants from all over the country. Fidel told them, referring to the policy change adopted: “(The) Yankees are the ones who are most worried, followed by the extremists there. I’m not going to mention the extremists here, so as not to confuse the confused with the extremists.”

The meeting was attended by “representative figures” of the emigration from all political tendencies — from a left that declared itself socialist, to conservatives of different stripes, and even former Bay of Pigs invaders and former members of the Batista dictatorship. The only persons not accepted were leaders of active counterrevolutionary organizations, who launched a brutal terrorist campaign against the so-called “dialogueros”. Carlos Muñiz Varela, Eulalio Negrín and Luciano Nieves, people from various political tendencies, became martyrs of this crusade.

More than 100,000 emigrants visited the country in 1979, and this had a profound impact on both Cuba and its emigration. On the basis of a rather simplistic criteria, unrelated to a better reading of the national reality, some attributed the events of Mariel, which occurred a year later, to the opening of relations with the island’s emigrants. However, Fidel had warned about the complexity of the policy undertaken and established guidelines for the strategic treatment of the phenomenon. In the aforementioned meeting he said:

“(A) policy of war always arouses more emotions (…) many times a policy of peace is more difficult to elaborate, to understand (…) If what we want with all our soul is for capitalism and imperialism to disappear, and we have however to carry out a policy of peaceful coexistence because it is the only one that can be done (…) socialism has to do it and must defend it.”

Fidel continued in his speech that day: “I cannot conceive the revolutionary in a state of pure asepsis, I cannot conceive him! (…) As if a true revolutionary could fear ideological contact, confrontation and contact (…) and we believe that we are all going to get bogged down by that. Perhaps we shine brighter, perhaps we can more legitimately say that we are pure.”

Another premise of the dialogue established by Fidel was to define it as a “national problem,” which could not be the subject of negotiations with the United States government: “that is the basic position,” he said at a press conference prior to the dialogue, held on September 6 of that year in Havana.

He also placed national culture as the unifying center of the convocation: “It does not matter what they are, if they are a millionaire in emigration or are a Cuban worker in emigration (…) this is not a class problem, it is a national problem (…) And that logically awakens our solidarity (…) It does not matter that they do not sympathize with the Revolution, but we are satisfied to know – and we see it, we verify it – that the Cuban community tries to maintain its language, their customs, their Cuban national identity.”

The “dialogue” was carried out against the dogmatists of the time, who, wrapped in a deceptive revolutionary intransigence, never stopped trying to trip it up. Its success, capable of overcoming all the vicissitudes that this policy has had to face, was based on the legitimate breadth of the call, as well as on the construction of an agenda that respected the various criteria and interests represented there.

The experience of this meeting sets guidelines for possible dialogue, even among very diverse political contenders, whether they are emigrants or live in the country. The line of demarcation is the defense of national sovereignty. Even those who are not socialists, but are patriots, surely recognize the validity that “that is the basic position,” as happened in 1978.