Why Elizabeth Warren makes bankers so uneasy, and so quiet

Let’s assume that when he woke up on the morning of Dec. 12, Michael Corbat, CEO of Citigroup, was feeling pretty good. The day before, the House of Representatives had passed a bill that would save his bank and others lots of money and headaches.

The trouble was, Elizabeth Warren, the senior senator from Massachusetts, was getting ready to speak on the Senate floor. She had his bank on her mind.

This story appears in the June 2015 issue of Bloomberg Markets.

What Warren wanted to talk about was an item tucked into page 615 of a 1,603-page spending package: the repeal of section 716 of the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act of 2010. Known as the swaps push-out rule, section 716 required banks to set up separate subsidiaries, not backed by the government, to trade certain derivatives. If the rule stood, it would generate huge administrative costs for the big banks.

Citi had fought hard on this. The bank’s lobbyists had worked on lawmakers and helped draft language for the repeal. Getting it into a big spending package Congress was sure to pass was a coup. In the ongoing wars between Wall Street and the forces of government regulation, this repeal was a big win for the banks.

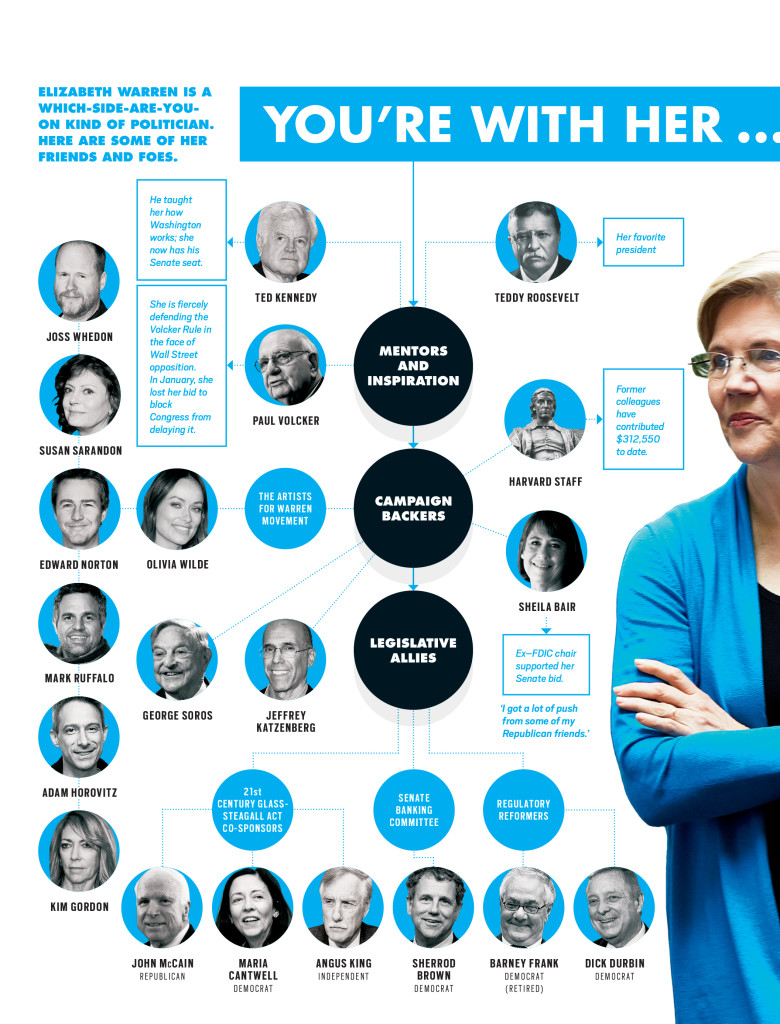

“Today I am coming to the floor not to talk about Democrats or Republicans,” Warren began her speech, “but to talk about a third group that also wields tremendous power in Washington—Citigroup.” With that, Warren turned Citi into exactly the kind of villain so many people suspect lurks in the backrooms of the Capitol. In one particularly striking moment, she connected nine top government officials—including Treasury Secretary Jacob J. Lew—directly to the megabank. She invoked Teddy Roosevelt, her favorite trust-busting president, who took on the big corporations of his day.

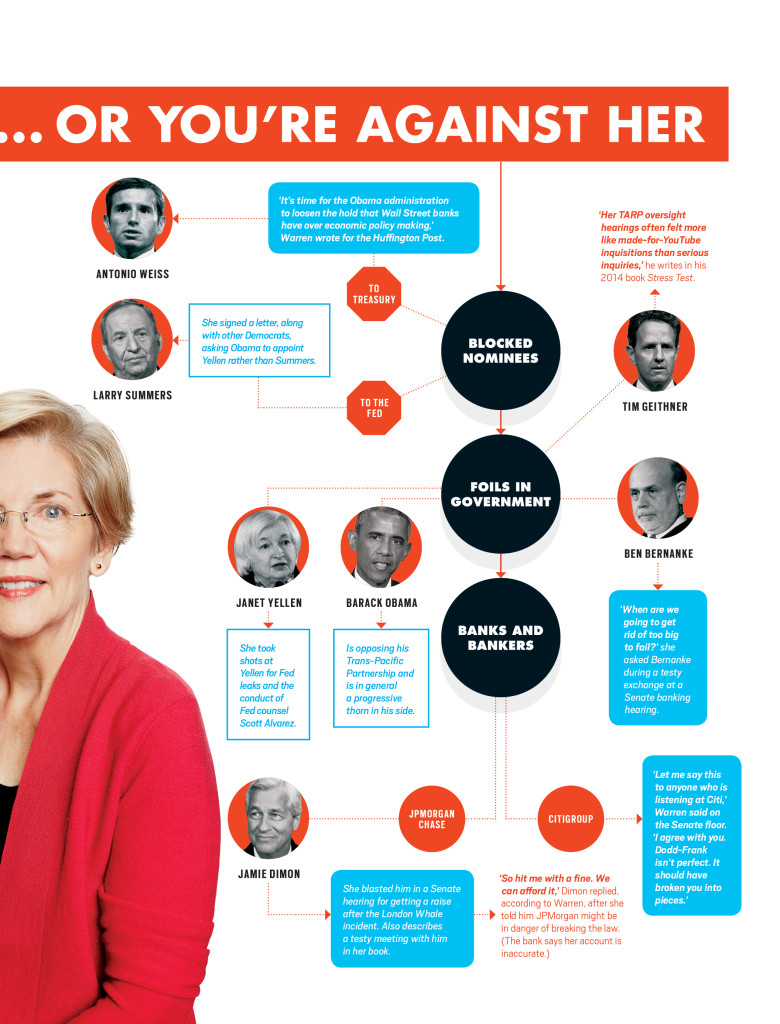

“There is a lot of talk coming from Citigroup about how Dodd-Frank isn’t perfect,” Warren continued. “So let me say this to anyone who is listening at Citi. I agree with you, Dodd-Frank isn’t perfect.” She paused, then spoke very slowly and emphatically: “It should have broken you into pieces.”

Warren didn’t succeed in blocking the bill. It passed the Senate the next day, and on Dec. 16, President Barack Obama signed it into law. But her clash with Citi generated the kind of headlines no bank wants to see these days. “Why Citi May Soon Regret Its Big Victory on Capitol Hill,” one from American Banker read. Warren’s speech got half a million YouTube hits. A few days later, protesters showed up outside Citi’s New York headquarters, holding placards that said things like “Break Up the Big Banks.”

Starting with December’s showdown with Citi, Warren, 65, has been on a tear, Bloomberg Markets reports in its June 2015 issue. Only two years into her term as senator, she has the kind of clout and attention it takes most lawmakers decades—or a presidential run—to build. Her stance as watchdog over the financial industry helped her win a Senate seat. Now, she’s harnessing that into something bigger and more powerful.

In January, Warren’s protests effectively blocked Obama from appointing Antonio Weiss, a banker at Lazard, to the No. 3 position at the Treasury Department. In February, she took on Federal Reserve Chair Janet Yellen, calling out the central banker for the conduct of Scott Alvarez, the Fed’s top lawyer, who criticized the swaps push-out rule in a speech. For months, she’s been attacking the Trans-Pacific Partnership, a treaty intended to regulate trade between North America and Asian countries outside of China. The White House wants the agreement badly; Warren casts it as a giveaway to multinational corporations.

Now, as the 2016 run for the White House begins, this could be a very hot campaign season for Wall Street. Warren, who declined to be interviewed for this story, is not running for president—although an army of supporters, including a corps of Hollywood celebrities, is clamoring for her to do so. But her impact on the race is already evident. There are frequent references to a Warren wing of the Democratic party and to the need to appeal to it. Hillary Clinton, the Democratic front-runner, is openly courting her. “Elizabeth Warren never lets us forget that the work of taming Wall Street’s irresponsible risk taking and reforming our financial system is far from finished,” Clinton wrote for Time magazine’s 100 Most Influential People issue in April.

Warren is a problem the financial industry didn’t expect to have right now. With the Republicans in control of Congress, this should be the time for Wall Street to soften regulators and their rules. The financial crisis is over, the housing market is recovering, and the economy is stable. A year ago, the sense of urgency about keeping a close watch over the financial industry seemed to be subsiding. Not anymore. Warren has re-sounded the alarm.

…

“More than any of the senators, she is making Wall Street nervous,” says Dick Durbin, a Democratic senator from Illinois and a fellow financial reformer. This spring, news broke that bank executives had told Democrats they were unhappy about the anti–Wall Street rhetoric coming from Warren and others. In some conversations, executives reportedly suggested they might withhold donations. Warren used the news as an opportunity to remind the public once again how banks wield power in Washington. “The big banks have issued a threat, and it’s up to us to fight back,” she promptly e-mailed supporters, asking for donations.

Barney Frank, the former congressman from Massachusetts and co-author of the Dodd-Frank legislation, says Warren has protected the act. “She can raise hell and make clear to people they will pay a political price if they try to attack it,” says Frank. In particular, he says, Warren has helped make modifying Dodd-Frank politically untenable for Democrats, without some of whom Republicans can’t hope to roll back the law. “I think it is safe until 2016,” Frank says.

“A Republican Senate would not take up Wall Street deregulation now,” says Dennis Kelleher, president and CEO of Better Markets, a watchdog organization that monitors Wall Street’s influence in Washington. “Nobody wants to be seen as siding with the big Wall Street banks.”

Not even the big banks. Executives at Citigroup, JPMorgan, Goldman Sachs, Bank of America, and other financial institutions declined to be interviewed for this story. Even the head of the Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association, or SIFMA, a lobbying group for the securities industry, wouldn’t discuss Warren publicly. “It would be foolish for financial institutions to get into a head-to-head with Senator Warren,” says Tony Fratto, a former Treasury official who is now a partner at the public-affairs consulting firm Hamilton Place Strategies. “It’s exactly what she wants, and it’s a debate you can’t win.”

Dodd-Frank has transformed Wall Street. The law created hundreds of new rules, which are enforced by more than a dozen regulatory agencies. One of them is the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, first envisioned by Warren while she was still a law professor at Harvard University. It’s tougher to get up to no good these days. It’s also tougher to make a buck.

Dodd-Frank has transformed Wall Street. The law created hundreds of new rules, which are enforced by more than a dozen regulatory agencies. One of them is the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, first envisioned by Warren while she was still a law professor at Harvard University. It’s tougher to get up to no good these days. It’s also tougher to make a buck.

Higher capital requirements and compliance costs are reshaping the industry. Banks are shedding operations that under the new rules are no longer worth the trouble. They’ve laid off thousands of traders, analysts, investment bankers, and support staff.

At the same time, they’re hiring armies of compliance officers. “It affects almost everything we do,” Lloyd Blankfein, CEO of Goldman Sachs, told Bloomberg in January. “I can’t think about our technology spend without thinking of the number of heads I have to hire to build the systems to comply with the new regulatory reporting functions.”

“The United States is at risk of losing its status as the world’s capital markets leader,” Daniel Gallagher, a commissioner at the Securities and Exchange Commission, said in a speech in January. “I see it everywhere: Rather than thinking creatively about ways to promote capital formation, legislators and regulators are layering on law after law, regulation after regulation—strangling entrepreneurs, their enterprises, and, of course, their employees and customers. We are not even resting on our laurels; we are actively throwing those laurels on a bonfire.”

Still, at this point, executives from the big banks tell Bloomberg they want the Dodd-Frank wars to be over; they’re digesting the new rules, and the costs, and trying to get back to making money.

For Warren, the fight is definitely not over. In April, in a speech titled “The Unfinished Business of Financial Reform,” she laid out how she hopes to move her agenda forward. Among other things, she called for the breakup of the big banks; they are still too big to fail, she said, and bailing them out of the next crisis would cost billions. And she wants jail time for managers who violate the law. “It’s time to stop recidivism in financial crimes and to end the ‘slap on the wrist’ culture that exists at the Justice Department and the SEC,” Warren said.

An important part of her legislative agenda is the 21st Century Glass-Steagall Act, which she and three co-sponsors introduced in 2013. The bill is a modern version of the 1933 law that split commercial and investment banks. (The original Glass-Steagall was effectively repealed in 1999.) So far, 21st Century Glass-Steagall hasn’t gained traction on Capitol Hill, but for Wall Street, this will be one to watch.

…

“There are only two things I’m looking for from the biggest financial institutions in this country,” Warren says one cool spring night in New York. She’s standing before a packed crowd on the fourth floor of a Barnes & Noble bookstore on 17th Street. She’s come here, while the Senate is in recess, to promote the paperback version of her autobiography, A Fighting Chance.

Dressed in black slacks and a purple blazer, her glasses perched on her nose, she looks like the law professor she once was. But she’s anything but bookish. She’s a great speaker. She recounts her girlhood in Oklahoma and her chaotic days as a young mother grinding through law school in a way that makes you feel as if you know her. She has a warm, easy smile. She tells jokes, laughs at herself. She has one very funny anecdote about nearly burning down her kitchen trying to make toast. At one point during her talk, reggae music inexplicably starts blasting through the bookstore—and she begins dancing to the beat.

Those two things she wants from the banks: “No. 1, I don’t think they ought to be able to cheat people,” Warren says. “Second thing, I don’t think they ought to be able to risk destroying this economy. Too big to fail has got to end.” The room erupts.

This is what Warren does better than anyone else: laying out the fight. There are good guys and bad guys—so pick a side. This helped win her an election. It draws crowds, produces YouTube hits, and sells books.

Warren’s arguments tap into very real worries. Wages are stagnating, and the gap between rich and poor is widening. Since the beginning of 2013, the world’s richest 100 people have gained $378 billion, according to the Bloomberg Billionaires Index. In an economic system that feels unfair and imbalanced, a lot of people are going to look for villains. Bankers make good ones. “We’ve given her a very easy target,” concedes one banking executive who asked not to be identified for fear of backlash against his institution.

A story Warren tells in her autobiography shows how expertly she can deliver a bad guy. In 2013, she writes, she had a meeting with Jamie Dimon, CEO of JPMorgan. They argued over the powers of the CFPB, she says, and at one point she told him that if JPMorgan wasn’t careful, it could end up in violation of the law. He replied, according to her: “So hit me with a fine. We can afford it.”

A JPMorgan spokesman says Warren’s account is inaccurate. Still, that’s almost beside the point. “She is perceived as the white hat,” says Tony Fratto.

Warren isn’t the only politician tapping into the public’s frustration and anger at the financial system. Other lawmakers have been vocal supporters of tighter regulation. David Vitter, a Republican senator from Louisiana, sided with Warren and other Democrats in December in their fight against Citi. “I know it surprised a lot of people,” he says, explaining that he also fears the risks posed by large institutions. “Too big to fail is alive and well.” In late April, Bloomberg reported that Vitter and Warren were working together on another piece of legislation, this one designed to curb the authority of the Fed to bail out banks in a crisis. John McCain, the senator from Arizona and former Republican presidential candidate, is a co-sponsor of the 21st Century Glass-Steagall Act, along with Democrat Maria Cantwell and independent Angus King.

Last fall, Clinton tried to mimic Warren’s populism, declaring in a speech, “Don’t let anybody tell you that it’s corporations and businesses that create jobs.” This was way off the mark Warren hit when she famously argued during her Senate campaign in 2011 that businesses owe some part of their success to citizens and to the government. (Obama echoed Warren’s rhetoric in his 2012 “you didn’t build that” speech.)

The Warren version is worth examining. It gives, in plain language, her view of American capitalism: “You built a factory out there? Good for you. But I want to be clear: You moved your goods to market on the roads the rest of us paid for; you hired workers the rest of us paid to educate; you were safe in your factory because of police forces and fire forces that the rest of us paid for. You didn’t have to worry that marauding bands would come and seize everything at your factory, and hire someone to protect against this, because of the work the rest of us did.”

…

On a cold winter day in Washington, a group of community bankers and credit union managers has traveled from across the country—Nevada, Georgia, South Carolina, New York—to testify before Warren and the other lawmakers who sit on the Senate Banking Committee. These guys are not Wall Street. They fund the local grocer or barber; they put people in their first homes.

They’ve come here for help. They say the Dodd-Frank rules meant to control the big banks are in fact crushing little ones. “Congress and regulators ask a lot of small, not-for-profit financial institutions when they tell them to comply with the same rules as JPMorgan, Bank of America, and Citibank,” Wally Murray, CEO of the Greater Nevada Credit Union, tells the senators. He points out that credit unions are now subject to more than 190 rule changes directed by some three dozen government agencies.

Coming at regulation through small banks is probably the banking industry’s best shot at rallying public support to repeal more of Dodd-Frank. Warren knows this, and so she listens with particular interest to the testimony of R. Daniel Blanton, a community banker from Augusta, Georgia. “My bank doesn’t represent a risk to anybody,” he says.

What draws Warren to him, though, isn’t his take on tough times in small-town Georgia. It’s his position as chairman-elect of the American Bankers Association, the trade group that is one of her oldest and toughest adversaries. Warren has accused the ABA of using the little banks it represents as fronts for the bigger ones it also represents.

“We’ve heard a lot today about how smaller banks are being smothered by unnecessary regulation, supposedly because of Dodd-Frank rules,” Warren says to Blanton after he finishes his testimony. “But a lot of the time, the legal changes they are asking for aren’t really about helping community banks.”

The tension level in the room ratchets up. What had been a humdrum hearing is about to become news. Those who spend time in banking hearings know the signs. Reporters and photographers are ready for exactly these moments. “All the cameras turn. You hear click-click. I tease her and say, ‘I’m just trying to get out of your shot,’” says Senator Heidi Heitkamp of North Dakota, a fellow Democrat who has the seat next to Warren’s in the committee room.

Warren begins by asking Blanton a series of increasingly uncomfortable questions. She asks for specifics on data and metrics that the banker, caught off guard, can’t provide. He looks flustered. At one point, Warren asks him to explain how a rules change he is recommending would affect not just his bank but also Wells Fargo, JPMorgan, and Citi. He throws up his hands and shakes his head, unable to answer her. “Maybe you can get back to me,” Warren tells Blanton coolly.

The exchange makes instant headlines. “Watch Elizabeth Warren Put a Banker in His Place,” a progressive website trumpets, with a video link to the testimony. Almost immediately after the hearing, Blanton’s e-mail begins filling up with people who’d watched it. “I had no idea so many people watched C-SPAN,” he says. Days later, back in Georgia, he can’t shake the encounter: “I keep thinking now of the things I should have said,” he says. “You know how that happens?”

Warren is moving on. In April, she lobbed a new attack at the White House over its refusal to provide details on negotiations over the Trans-Pacific Partnership. “The government doesn’t want you to read this massive new trade agreement. It’s top-secret,” she wrote on her website. “We’ve all seen the tricks and traps that corporations hide in the fine print of contracts. We’ve all seen the provisions they slip into legislation to rig the game in their favor. Now just imagine what they have done working behind closed doors with TPP. We can’t keep the American people in the dark.”

This story appears in the June 2015 issue of Bloomberg Markets.