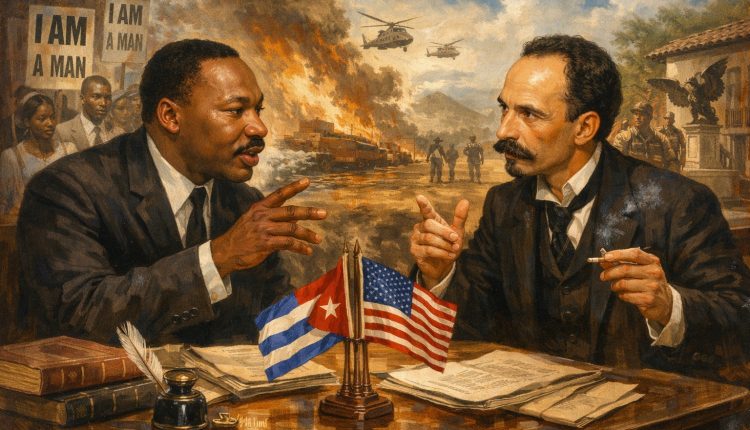

When Martí met King: A conversation across empires

At the end, the questions remain—hanging over a hemisphere still wrestling with color lines, labor lines, and gunboat lines.

(Editor’s Note: Today, Jan. 15, is the birthday of slain civil rights leader and philosopher-prophet Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Later this month, we celebrate José Martí’s birthday. Martí was a 19th-century Cuban nationalist, poet, philosopher, essayist, journalist, translator, professor, and publisher, and one of the island’s most important national heroes. So I asked ChatGPT, an artificial intelligence, to imagine a conversation between these two great and influential leaders who lived a century apart. What follows is the result.)

***

The room is spare but sunlit. Outside, there is no clear geography—no Havana, no Montgomery—only the sense of a hemisphere listening. Two men sit across from each other: one born enslaved by Jim Crow’s long shadow, the other by a dying Spanish empire and the rising ambitions of a new one.

José Martí speaks first.

Martí: I once said that the task of humanity is to prevent injustice. Yet injustice has proven remarkably adaptable. It changes uniforms, flags, and languages. Doctor King, you confronted it in the streets of America. Did you believe the Republic could be redeemed?

King: I believed—and still believe—that “the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.” But I also learned that it does not bend on its own. It bends because people apply pressure. Sometimes the greatest illusion is that injustice survives only because it is misunderstood, when in fact it survives because it is profitable.

Martí: Ah—profit. The oldest theology. In my time, Spain ruled Cuba with bayonets, but I warned my people that another power was waiting offshore. I said, “I have lived in the monster, and I know its entrails.” I was not speaking metaphorically.

King: Nor was I when I warned my own country that it was becoming “the greatest purveyor of violence in the world today.” Many preferred the earlier version of me—the one who spoke of dreams without naming the systems that crush them.

Martí: Empire prefers poets when they sing softly, not when they point. Tell me, Doctor King: in your struggle, was race the central wound—or merely the most visible one?

King: Race was the blade, but economics was the handle. Segregation was not only humiliation—it was theft. Stolen wages, stolen opportunity, stolen dignity. That is why, near the end, I spoke less of integration and more of guaranteed work, of a right to live. A nation that can put a man on the moon can put a man to work.

Martí: You speak like a Latin American without realizing it. Our wars for independence were never only about flags. They were about land, labor, and the right to stand upright. I warned that “a people that does not know its own history is like a man without memory.” Yet the hemisphere keeps being told its poverty is a personal failure.

King: That story is familiar. We were told that if Black Americans worked harder, protested less, and waited patiently, freedom would arrive on schedule. But freedom delayed is freedom denied. Poverty, too, is a form of violence—slow, bureaucratic, and perfectly legal.

Martí: And when nations resist that violence?

King: They are called ungrateful. Or dangerous. Or communist. The labels change; the punishment does not.

Martí: In my lifetime, the United States spoke of liberty while preparing to inherit Spain’s colonies. I feared that Latin America would exchange one master for another—one who smiled more convincingly. You lived long enough to see that fear fulfilled.

King: I did. And I saw how racism at home made imperialism abroad possible. A nation that dehumanizes its own people will find it easy to dehumanize others. Vietnam taught me that. So did Latin America.

Martí: Then we agree on this: there can be no justice in one nation built on the subjugation of another.

King: Exactly. Or as I once said, “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.” Borders do not absolve morality.

Martí: Nor does time. Doctor King, what would you say to those today who admire your words but reject your conclusions?

King: I would tell them that quoting me without confronting militarism, racism, and economic exploitation is a form of dishonesty. Dreams are not decoration. They are demands.

Martí: Well said. I would add that independence without dignity is only a change of management.

The light shifts. The conversation ends, but the questions remain—hanging over a hemisphere still wrestling with color lines, labor lines, and gunboat lines.

Two men from different centuries rise from the table having agreed on one thing: Justice is not a slogan. It is work. And it is unfinished.