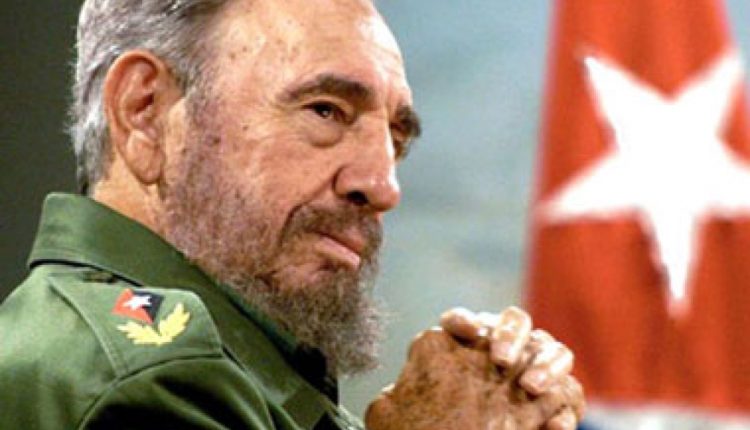

Fidel Castro and the dialogue with Cuba’s emigrants

HAVANA – Fidel Castro convened an unusual conference with the American press in 1978 to discuss issues related to the Cuban community abroad. The name itself pointed to a substantial change from what was common to that point. Emigrants were no longer called “sellouts” or “exiles” (as they were referred to in the U.S.), but Cuban humor described the phenomenon as the metamorphosis of the worms* into butterflies.

Journalists expected some kind of amnesty for the thousands of political prisoners being held in Cuba, as well as the authorization of visits by emigrants, which was facilitated by Jimmy Carter’s decision to lift the ban on travel of Americans to Cuba.

Although these and other requests were eventually met, since more than 2,500 political prisoners (almost all) were freed, and more than 100,000 emigrants visited the country in 1979, everything seems to indicate that Fidel Castro did not want to reduce the process to simply satisfying certain demands, however important they may have been. It dealt with starting a new relationship with the emigrants which resulted in the dialogue with representative figures of the Cuban community abroad, that was convened a few months later.

This new relationship began by recognizing the existence of the Cuban community abroad as a social entity, which may now seem obvious, but at the time signified an enormous step forward because of its political implications. “This implies a recognition of the community’s existence, let us call it a recognition that the community exists and a willingness to talk to that community,” Fidel said in an interview explaining what was to come.

To accomplish this it was necessary to break with the stereotyped vision that existed of the emigrants, and adapt Cuban policy to the reality of both societies. Fidel recalled that there were thousands of Cubans who emigrated to the United States before the triumph of the Revolution and that, even most of those who did so later, had never participated in counterrevolutionary activities. “Because unfair generic terms were used here —we have all used them— in reference to the emigration.”

None of the social changes generated by the arrival of new Cuban immigrants after 1980, or the demographic impact determined by the relative growth of descendants in the social group, much less the transformations of Cuban society regarding its vision of the migratory phenomenon and relations with emigrants, had yet to occur. But an evolution in perception was obvious. In that sense, Fidel said, “There has been a certain change in attitude, both in the mass of the Cuban community abroad and in the opinion of our people, of the Revolution in general.”

Calling for a dialogue was an act against dogmatism that often prevailed in certain sectors of Cuban society, and in some of its leaders. All you need is to review some of the reactions it provoked inside and outside of Cuba. In a meeting with hundreds of people arranged by Fidel precisely to explain the policy towards emigration, I heard him say that only conservatives from there and here opposed it.

“Don’t think this will be easy,” he told one of the reporters. “We need people to understand this, because we cannot do things behind the people’s backs … If they don’t understand, we cannot achieve this.”

The other ingredient of the new relationship was that the emigrants feel that they were being heard by the Cuban government. “We have become aware that there are a number of problems that interest the Cuban community,” said Fidel. “And we are willing to discuss these problems with Cubans abroad … we are open-minded and willing to discuss all issues that interest the Cuban community.”

In the so-called “Dialogue” a very broad spectrum of political and ideological tendencies was represented. From defenders of the Cuban Revolution, to former ministers of the Batista dictatorship, including participants in the Bay of Pigs invasion, were present at the meeting. The only people excluded were those still active in counterrevolutionary groups because, according to Fidel, “We are not willing to debate with the counterrevolution.”

Fidel Castro argued that one of the factors that indirectly facilitated the convening of these meetings had been the change of U.S. policy towards Cuba during the Carter administration, especially the suspension of support for terrorist activities. However, he emphasized that relations with Cuban emigrants constituted an internal matter, not the subject of negotiations with the United States.

Perhaps the most transcendent of Fidel’s ideas about Cuba’s immigration policy was one that came from the concept that “it is not a class issue here, it is a national problem (…) It does not matter that they do not sympathize with the Revolution, but we are pleased to know (…) that the Cuban community tries to maintain its language, its customs, its Cuban national identity. And that,” he insisted, “awakens our sympathy and solidarity, even if they don’t sympathize with the Revolution.”

The dialogue interrupted almost two decades of isolation and rejection and began a path to coexistence with its emigrants. Indeed, it has not been easy: U.S. policy has remained almost unchanged, there exists a Cuban-American right determined to hinder any contact, and stereotypes in Cuba that slow the dynamic to advance towards greater goals, still exist. And yet, it is also true that obstacles that seemed insurmountable have been overcome.

Now, as Fidel predicted in 1978, we are focused on the need for a qualitative leap in Cuba’s relations with its emigration. It is no longer enough to accept certain contacts with emigrants, but to integrate them organically to the destinies of the nation. More than ever, it is “a national problem,” which can only be solved among Cubans.

Note: All quotes are from “Fidel’s interview with a group of Cuban journalists who write for the Cuban community abroad and several American journalists,” Social Sciences Editorial, Havana, 1978.

* At the start of the Cuban Revolution Cubans leaving the Island were often referred to as worms.