U.S. sanctions cruelly choke ordinary Cubans

Washington claims they are leverage against an authoritarian government, but in reality, they function as a broad economic chokehold that tightens around the lives of ordinary people.

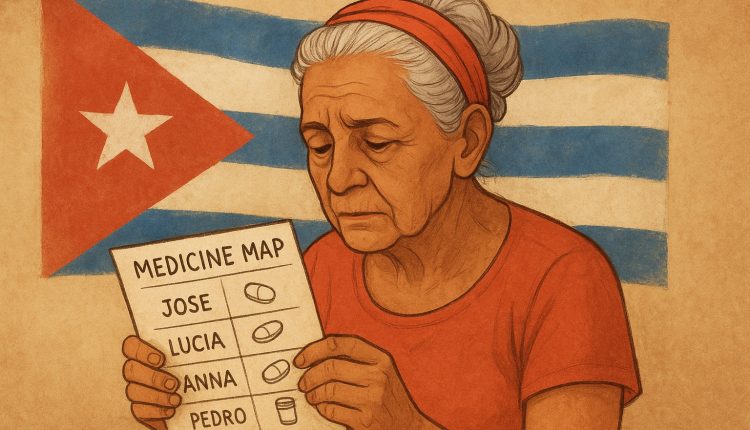

María Elena keeps a handwritten list taped inside her kitchen cabinet in Centro Habana. It’s her family’s “medicine map” — the cousins in Tampa who might send blood-pressure pills, the friend in Madrid who sometimes finds antibiotics, the neighbor who trades insulin she received from a church group. At 72, she spends more time on this scavenger hunt than on managing her own heart condition. “There’s nothing in the pharmacies,” she said. “Nothing.”

This is the real daily impact of U.S. sanctions on Cuba. Washington claims they are leverage against an authoritarian government, but in reality, they function as a broad economic chokehold that tightens around the lives of ordinary people like María Elena — not the officials in Havana.

A United Nations human rights expert recently concluded that U.S. measures are “causing significant effects across all aspects of life” in Cuba and called for their removal. The review found that sanctions — in place for over six decades — have increased substantially since 2018, with a particularly damaging escalation in 2021 when Cuba was again added to the U.S. list of “state sponsors of terrorism.” That designation not only increased pressure but also effectively cut Cuba off from routine global banking.

The consequences ripple through every household. Remittances, for many Cuban families the most reliable source of money for food and medicine, have become a political football in Washington. When the U.S. restricted formal remittance channels and companies like Western Union halted operations on the island, those lifelines became uncertain or vanished altogether. Families had little choice but to turn to informal couriers who charged high fees and offered no guarantees.

Banking isolation worsens every hardship. Global banks, afraid of breaking U.S. rules, have long practiced “de-risking” — refusing to process even legitimate transfers involving Cuba. That means that a small private restaurant might have no way to accept a payment from a foreign supplier. A humanitarian organization could see a hospital supply purchase blocked by an overly cautious bank algorithm.

Supporters of the embargo often point to the Cuban government’s own shortcomings — including centralized controls, political repression, and slow reforms. Those criticisms may be justified. However, the embargo, as it is implemented, does not specifically target repression; it impacts the economy as a whole. And the people with the least influence on national policy are the ones bearing the highest costs.

Human-rights groups and international observers have repeatedly documented shortages of basic medicines, food staples, electricity, and clean water. Hospitals operate without essential equipment. Schools lack supplies. Inflation and scarcity push families into exhausting survival routines: standing in long lines for cooking oil, bartering for antibiotics, and improvising electricity backups during blackouts. These conditions long predate the pandemic or global inflation.

Sanctions also distort Cuban politics in ways policymakers in Washington rarely recognize. Broad economic pressure provides Havana with a convenient scapegoat. When the U.S. blocks payments or restrictions hinder commerce, Cuban officials blame shortages on “el bloqueo,” and many citizens — experiencing the immediate effects — believe them. Sanctions allow the government to shift public frustration outward, reducing the impact of its own policy failures.

So, what would a more humane and effective policy look like?

First, differentiate between targeted and broad sanctions. Actions focused on specific officials responsible for human rights abuses can stay in place without disrupting remittances, humanitarian trade, or financial channels for the private sector.

Second, restore protected corridors for family remittances, civil-society exchanges, and small business activities. These are the true engines of openness in Cuba — and the most direct links between Cuban families and the outside world.

Third, collaborate with European and Latin American partners to decrease bank over-compliance. Most banks avoid Cuba not because they have to, but because the risks and paperwork outweigh the benefits. Multilateral clarity and humanitarian carveouts could alter that behavior.

Finally, judge sanctions by their results, not by symbolism. If the aim is democratic reform, then a policy that worsens scarcity and encourages migration but keeps the political system the same is a failed policy — one that needs reassessment, not complacency.

Lifting or softening sanctions is not an endorsement of the Cuban government; it is a recognition that punishing civilians is neither moral nor strategically effective. After 60 years, the embargo has not brought about change. It has caused shortages, despair, and an aging woman in Havana who maintains a “medicine map” instead of enjoying her retirement.

It’s time for a policy that benefits the Cuban people — not one that makes their lives more difficult in the name of helping them.