The Seventh Party Congress in its international context

HAVANA — The Seventh Congress of the Communist Party of Cuba will be held this weekend [April 16-18] and its importance has escaped no one.

It will be the last one presided by the historical generation of the Cuban Revolution and, although it will have to evaluate the results of the transformations approved in the previous Congress, its principal challenge will be to satisfy the nation’s expectations regarding its future projection.

In this context, an analysis of the international juncture in which the Congress will proceed and the gathering’s outlook acquires a special relevance.

The Sixth Congress (2011) was characterized by the institutionalization of the changes in the Cuban economic model and involved the articulation of a consensus that implied a broad popular discussion about its main documents.

In that manner, the Congress attempted to adjust the nation’s economy to its own domestic needs, to overcome economic and political deficiencies that had been harshly criticized, to improve Cuba’s insertion into the international market and to advance toward integration with the rest of the Latin American countries.

The moment indicated a juncture that was particularly favorable to these goals. Hugo Chávez’s victory in Venezuela 12 years earlier — especially its gradual consolidation after the quashing of the coup attempt in 2002 — became the origin of profound transformations in Latin America’s political environment.

Through the social movements, Evo Morales and Rafael Correa rose to the presidency of Bolivia and Ecuador, respectively. To this was added the presence of Ignacio Lula da Silva in Brazil; Néstor Kirchner and Cristina Fernández in Argentina; the Frente Amplio government in Uruguay and the Sandinist government in Nicaragua.

Also, a very generalized consensus on Latin American integration was established at a very favorable moment in the region’s economy, as a result of an increase in the prices of raw materials.

In the decade prior to the Sixth Congress, the idea of creating a North American Free Trade Area (NAFTA), promoted by the United States, was discarded. Other independent regional blocs emerged or became stronger, such as the Union of Southern Nations (UNASUR), the Bolivarian Alliance for the Peoples of Our America (ALBA), and the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (CELAC).

CELAC is the most encompassing of all, because all the countries in the hemisphere are represented in it, except for the United States and Canada.

This way, in a very short time, Cuba found itself fully inserted in a regional environment from which it had been excluded by U.S. policy. In particular, Cuba’s economic pacts with Venezuela filled in part the vacuum created by the disappearance of the Soviet Union and the socialist bloc in Eastern Europe.

The improvement in Cuba’s economic and political environment was aided by China’s forceful emergence in the region, Cuba’s relations with Russia and Canada, the strengthened relations with Third World countries that were significantly improving their situation (such as Vietnam and Angola), and the growth of investments from various European capitals.

All of this created a very broad framework of international relations, even though the U.S. blockade remained a huge obstacle to their development.

Just two years before the Sixth Congress was held, Barack Obama assumed the presidency of the United States. He came to power amid an economic crisis that threatened the system and an international discredit that resulted from the “war on terrorism” launched during the administration of George W. Bush.

Obama’s discourse, his personality and the fact that he was the first African-American president in the nation’s history stirred enormous expectations throughout the world, especially in Latin America after he announced “a new beginning” in U.S. relations with the region.

Although in the case of Cuba Obama only adopted measures that amended the Bush administration’s most unpopular rulings, their mere presence softened the more aggressive aspects of the previous policies and created the hope to advance toward an improvement in bilateral relations.

That aspect was highlighted by President Raúl Castro in a speech to the Sixth Congress, when he said:

“We reiterate our disposition toward a dialogue and will assume the challenge of maintaining a normal relationship with the United States, in which we can coexist in a civilized manner despite our differences, on the basis of mutual respect and noninterference in [each other’s] domestic affairs.”

That possibility took three years to become a fact. One and a half years were spent in secret negotiations until, on Dec. 17, 2014, both presidents announced the beginning of a process directed toward the normalization of relations between the two countries.

No doubt, one of the reasons that conditioned Obama’s decision was the unanimous stance taken by Latin America and the Caribbean when they demanded Cuba’s participation in the Seventh Summit of the Americas set for Panama in 2015.

At that time, Latin America presented a rather homogeneous international position, with a predominance of progressive popular governments. Obama himself declared that the U.S. found itself isolated in the region as a consequence of its policy toward Cuba.

That scenario has changed sharply in recent months. The economic crisis that resulted from a plummeting of the prices of oil and raw materials made it very difficult to keep up the social policies that were the base of progressive governments, affecting their very existence.

The death of Hugo Chávez [in March 2013] complicated the domestic situation in Venezuela leading to a loss of the government’s majority in Parliament in the latest elections. The right also won the presidential elections in Argentina, and Dilma Rousseff is facing the possibility of a parliamentary coup in Brazil. Though they still enjoy widespread popularity, Morales and Correa have had to face setbacks and defeats.

All this affects the consensus to integrate — required by the political will — given the fact that Latin American economies do not fully complement one another and that they depend on markets outside the region.

The United States has not kept distant from this process, sponsoring right-wing forces, promoting bilateral or multilateral free-trade accords (especially in the Pacific) and restructuring its political influence in the region thanks to the emergence of governments sympathetic to Washington.

Such is the adverse scenario in Latin America that looms before the Seventh Congress of the Communist Party of Cuba. In its favor we can mention the advances in relations with the United States, which, paradoxically, have not been affected by the progressive setbacks in the region. This demonstrates that the new policy toward Cuba responds to objective factors that will be hard to reverse.

More important still, the new environment of Cuba-U.S.relations opens spaces for Cuba’s international economic relations, as shown by Havana’s recent accords with the European Union and the growing interest shown by foreign investors — including U.S. investors — in the Cuban market.

None of this implies that we have come to a solution to the systemic contradictions present in Cuba-U.S. relations, or to the challenges to Cuban socialism posed by an international environment ruled by the globalization of capitalism under the preeminence of U.S. hegemony.

The success of the forthcoming Congress will depend greatly on establishing the guidelines that will rule Cuban policy in this context, as well as Havana’s ability to reinforce a domestic consensus under the conditions imposed by this complex international scenario. Therein lies its transcendence for the future of Cuba.

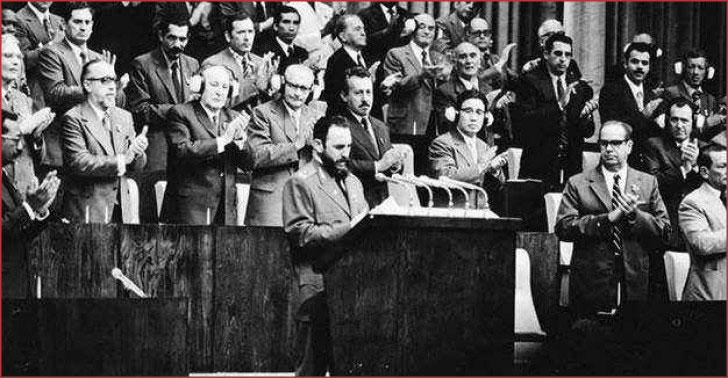

[Photo at top: Fidel Castro addressing the First Party Congress in December 1975.]