The Cry of Lares

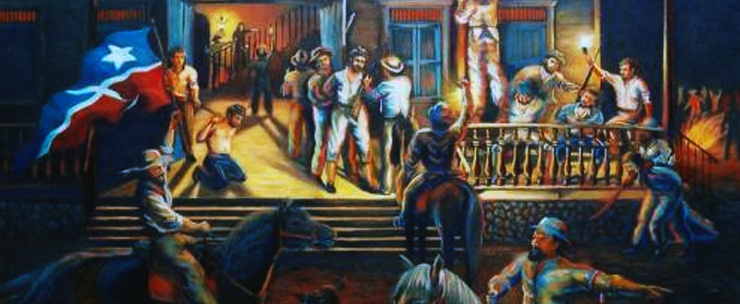

HAVANA – September 23 is the annual commemoration of the so-called Cry of Lares, an event that signaled the start of the Puerto Rican independence struggle against Spain in 1868.

As often happens, what is celebrated is a military defeat. That day, a group of patriots, pressured by circumstances, move up the date planned for the uprising, seizing the town of Lares, establishing a provisional government and declaring the Constitution of the Republic of Puerto Rico.

The haste of the event prevents effective coordination with other revolutionary groups in the country. Its main leader, Ramón Emeterio Betances, who was in exile, could not arrive in time to Puerto Rico and the weapons he had obtained abroad were seized on the island of St. Thomas, then owned by the Danes. All of this led to the rapid capitulation of the rebels and the arrest of its top leaders.

However, this foiled act of rebellion will have cultural and political consequences that will forever mark the history of Puerto Rico. The very conscience of Puerto Rican nationality, still in its infancy due to the heterogeneity of its components, took form in that attempt at liberation, shaping a national culture that has been able to withstand all the vicissitudes of foreign domination. What no one has been able to take away from Puerto Ricans is the pride of being Puerto Rican.

As much as Spaniards and North Americans have tried to erase the Cry of Lares from history and as much as annexationists and reformers have tried to turn it into a simple anecdotal event lacking in immediacy, it has inspired Puerto Rico’s struggles for independence up to the present. Not only for its patriotic meaning, but also because the Lares project was ahead of its time, proposing a model of Caribbean integration that remains absolutely valid.

In the late 19th Century, José Martí understood the international dimension of the independence of Cuba and Puerto Rico:

“The Free Antilles will rescue the independence of Our America, and the honor – questionable and damaged – of English America, and perhaps accelerate and set the balance of the world […] It is a world that we are balancing; it is not just two islands that we’re going to liberate.”

For that reason, the first of the bases of the Cuban Revolutionary Party, founded by Marti in 1892, establishes that the party “is created to achieve the absolute independence of Cuba and to encourage and aid that of Puerto Rico.”

While it is true that the logic of Marti’s thoughts led inevitably to this conclusion and had roots in the Bolivarian liberation plans, one of his closest influences must have been Ramón Emeterio Betances, whom Martí knew personally and collaborated with. Twenty years before José Martí, Betances had advanced a similar opinion:

“Let us grow closer together! Vainly will Spain try to crush the insurrection to sell Cuba to the United States, which would be the beginning of the absorption of all the Antilles by the Anglo-American race.

“Let us unite! Let us create one people, a nation of true masons, so we can build a temple with foundations so solid that all the forces of the Saxon and Spanish races together can never tear it down. We shall fight for independence and in the shade shall engrave this inscription, as enduring as the country, which is a dictate of our interest and our heart, the most generous way of acting and the most selfish instinct of self-preservation: ‘The Antilles for the Antilleans.’”

Betances was one of the men who, in 1865 in New York, inspired the Constitution of the Republican Society of Cuba and Puerto Rico, apparently, the first coalition aimed at fighting for the independence of both countries. In it, he tried to convince the conspirators that the aim should be to develop a joint revolution to “form tomorrow the Confederation of the Antilles,” as he said in a proclamation issued in July 1867.

Unfortunately, the Cuban patriots at the time were not ready to understand the scale of this project and even though the cries of Lares and Yara, which also started the war in Cuba, practically coincided, they were not properly coordinated. The same happened when José Martí died fighting in Cuba in 1895, and Puerto Rico’s liberation project, from an Antillean vision of the war, ends up being discarded by the new authorities of the Cuban Revolutionary Party.

The result was precisely what Betances and Marti feared. The United States intervened in the Cuban war adulterating Marti’s pro-independence objectives; it restored colonial rule in Puerto Rico and established a stranglehold on the Caribbean region that served as a springboard for its expansion to the rest of Latin America.

Those who today argue that the independence of Puerto Rico is not feasible for economic and political reasons, should turn to the Martí-Betances plan and understand that its conditioners lie in integration. The rest of the Caribbean countries, more diverse and less financially endowed than the former Spanish colonies, have understood this and have acted accordingly.

It has also been interpreted thus by the pro-integration processes in Latin American, which do not exclude Puerto Rico from their objectives. Perhaps, the dream of Lares is not so distant because Betances and Martí are still with us.

Progreso Semanal/ Weekly authorizes the total or partial reproduction of the articles by our journalists so long as source and author are identified.