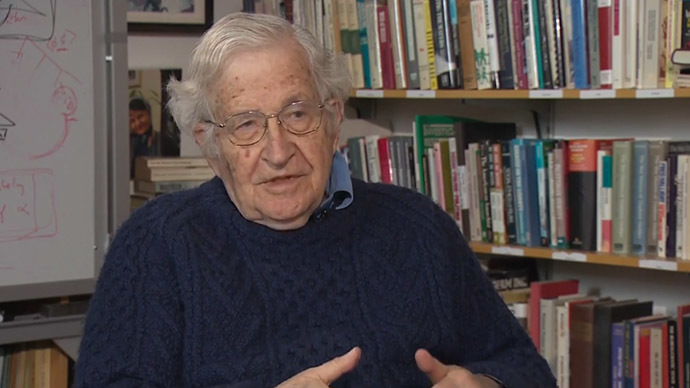

Chomsky: ‘International law cannot be enforced against great powers’

While the International Criminal Court investigates and sentences African dictators, any of the crimes the US commits like the invasion of Iraq, which has destabilized an entire region, go unpunished, philosopher Noam Chomsky tells RT.

RT: During a congressional hearing [on April 15, officially titled ‘Confronting Russia’s Weaponization of Information’], House Foreign Affairs Committee chair Ed Royce said, “The Russian media is now dividing societies abroad and, in fact, weaponizing information.” Where is that coming from? Is it a genuine fear or fear of alternative opinions?

Noam Chomsky: He’s talking about the Russian media but if there were any imaginable possibility of honesty, he could be talking about the American media, for which that is correct. Take the New York Times — the greatest newspaper in the world. Take one example, at the first article that appeared today, that the tentative [nuclear] agreement with Iran was reached. It’s a thinkpiece, by Peter Baker, one of their main analysts. He discusses in it the main reasons to distrust Iran, the crimes of Iran. It’s very interesting to look at. The most interesting one is the charge that Iran is destabilizing the Middle East because it’s supporting militias which have killed American soldiers in Iraq. That’s kind of as if, in 1943, the Nazi press had criticized England because it was destabilizing Europe for supporting partisans who were killing German soldiers. In other words, the assumption is, when the United States invades, it kills a couple hundred thousand people, destroys the country, elicits sectarian conflicts that are now tearing Iraq and the region apart, that’s stabilization. If someone resists that tact, that’s destabilization.

That’s characteristic. The Summit of the Americas is meeting now in Panama. Take a look at the commentary on it here [in the US]. The big question is how much credit Obama will get for his move towards helping Cuba escape from its isolation in the hemisphere. It’s exactly the opposite. The United States is isolated in the hemisphere. You look back at the last hemisphere meeting in Colombia, a US ally. The United States was totally isolated. There were two big issues. One was admitting Cuba into the hemisphere. Everyone wanted it. The US refused, along with Canada. The other was the drug war, which the US insists on, and the Latin American countries who are being seriously harmed by it, they want it significantly modified, decriminalized and so on. And, again, the US was totally isolated. Those were the two main issues.

As for the steps towards Cuba, they’re described as noble gestures. The picture is that we’ve — exactly as Obama said — we’ve tried for 50 years to bring freedom, justice, and democracy to Cuba, but our methods have failed, so we might try some other methods to achieve these noble goals. The facts are very clear. This is a free and open society, so we have access to internal documents at an extraordinary level. You can’t claim you don’t know. It’s not like a totalitarian state where there are no records. We know what happened. The Kennedy administration launched a very serious terrorist war against Cuba. It was one of the factors that led to the missile crisis. It was a war that was planned to lead to an invasion in October 1962, which Cuba and Russia presumably knew about. It’s now assumed by scholarship that that’s one of the reasons for the placement of the missiles. That war went on for years. No mention of it is permissible. The only thing you can mention is that there were some attempts to assassinate [Fidel] Castro. And those can be written off as ridiculous CIA shenanigans. But the terrorist war itself was very serious. That was a footnote to it.

The other, of course, was a crushing embargo. We also know the reasons, because they’re stated explicitly in the internal documents. Go back to the early ‘60s, as the State Department explained, the problem with Castro was his successful defiance of US policies that go back to the Monroe Doctrine — 1823. The Doctrine asserted that the United States has the right to control the hemisphere. They couldn’t implement it at the time, but that’s the Doctrine. And Cuba was successfully defying that Doctrine. Therefore, we have to carry out a terrorist war and crushing embargo that have nothing to do with bringing freedom and justice to the Cubans. And there is no noble gesture, just Obama’s recognition that the United States is practically being thrown out of the hemisphere because of its isolation on this topic.

But you can’t discuss that [in the US]. It’s all public information, nothing secret, all available in public documents, but undiscussable. Like the idea — and you can’t contemplate the idea — that when the US invades another country and the other resists, it’s not the resistors who are committing the crime, it’s the invaders. And we, of course, understand that very well when, say, Russia invaded Afghanistan. If somebody resisted it, we don’t say they’re criminals, they are destabilizing Afghanistan. Maybe Pravda said that, I doubt it. But here, it’s normal.

So if the House wants to study the weaponization of the media, they can look right at the front pages of the newspapers that they get every day.

RT: Our network has come repeatedly under attack, even from State secretary John Kerry. Recently, he said, “RT’s influence is growing,” while his very own deputy, Victoria Nuland, said that nobody watches RT in America, which is probably not true. Do you think this is about money? Because we know that the BBG — the Broadcasting Board of Governors — has a budget of $750 million as opposed to RT’s $250 million, which has never been a secret. Or is it something else?

NC: I think it’s something else. I don’t think they care about the money. The idea that there should be a network reaching people which does not repeat the US propaganda system is intolerable.

RT: To them.

NC: Yes. That’s normal.

RT: As for US-Russia relations, are we really in Cold War version 2.0?

NC: It’s dangerous. The Bulletin of Atomic Scientists has a famous doomsday clock. It goes back to the late 1940s. The clock is placed several minutes before “midnight.” Midnight means we’re done, finished. They just moved it two minutes closer to midnight — three minutes from midnight. That’s the closest it’s been since the early 1980s when there was a major war scare. We now know how serious that war scare was. It wasn’t quite understood at the time, but it was very serious. Now it’s moved that close. One of the reasons is the deterioration in Russia-US relations, which is quite threatening. The other is environmental catastrophe, which we weren’t thinking about then. But, yes, that’s serious.

RT: Is it all because of the Ukrainian crisis?

NC: Partly. It’s also because of other domains in which Russia and the United States don’t see eye to eye. Just as there is a US-Iranian crisis. Everyone in the United States — every leading commentator, every presidential candidate and so on, recently Jeb Bush — says Iran is the greatest threat to world peace. That’s repeated over and over.

There’s also another opinion on the matter. Namely, the world’s opinion, and we know what that is because there are polls taken by the leading US polling agencies. The Gallup organization has international polls. And they ask the question, “Which country is the greatest threat to world peace?” The United States is way ahead of anyone else. No other country is even close. But Americans are protected from that. The US media simply refused to print it. This major poll, I think it was December 2013, it was reported by BBC. But not a single word in the major American media. So if the world thinks that, so much for the world. We say Iran is the greatest threat to world peace, therefore that is true. We can repeat it over and over.

The major newspapers in the United States — the New York Times and the Washington Post — have recently published op-eds by prominent figures calling for bombing Iran right now. How would we react if Kayhan, say, or Pravda, or any newspaper, published articles by leading figures saying ‘let’s bomb the United States right now’? I mean, there would be a reaction. There would. But if this happens here, it’s perfectly fine. It’s normal.

If we look closely at the conflicts, we can find plenty of problems with both sides. But the way they’re interpreted here is that we’re necessarily right about everything, and if anyone’s in the way, they are wrong about everything. I wouldn’t say there’s no disagreement on that, there’s some. Take for example Ukraine. The standard position here is that it’s all the fault of the Russians, it’s Russian aggression and so on. However, you can read — not in the mainstream press, but in prominent journals — different opinions. So in Foreign Affairs, the leading establishment journal, you can read alead article on the front, the West is responsible for the Ukraine crisis.

RT: The West or particularly the United States?

NC: Well, the West means the United States and everyone else goes along. What’s called the international community in the United States is the United States and anyone who happens to be going along with it. Take, say, for example, the question of Iran’s right to carry out its current nuclear policies, whatever they are. The standard line is that the international community objects to this. Who is the international community? What the United States determines it to be. The latest meeting of non-aligned countries — the large majority of the world’s population — the last meeting happened to be in Tehran, where they once again — they’d done it before — vigorously endorsed Iran’s right to pursue its nuclear programs in accord with the provisions of the non-proliferation treaty, which allow that. But they’re not part of the international community [to the US]. They may be the majority of the world, but that’s not the international community. Any reader of [George] Orwell would be perfectly familiar with this. But it continues virtually without comment.

RT: If we are to assume that the US is the root of the problem in Ukraine, what is the endgame? What would Washington want out of this? Destroying Russia-Europe ties?

NC: I wouldn’t say it’s just the US. I don’t agree with that. I think it’s more complex. But a large part of the problem is what [John] Mearsheimer [author of the Foreign Affairs piece on Ukraine] described. It goes back to the breakup of the Soviet Union — roughly 1990. At the time, there were many questions. One question was, what happens to NATO? If you had accepted the propaganda of the past — since the late 1940s or 1950 — you would’ve said ‘NATO should disappear.’ NATO was supposed to protect Western Europe from the Russian hordes. Okay, no more Russian hordes, now what happens to NATO? The question of its disappearance didn’t even arise. [Mikhail] Gorbachev made a pretty remarkable proposal. He offered to let Germany be unified and to join NATO, a hostile military alliance. You look at the history of the century, that’s a pretty astonishing move.

There was a quid pro quo, that NATO not expand one inch to the east. That was the phrase that was used in diplomatic interchanges. That meant East Germany. There was no thought of it expanding beyond. Of course, NATO, at once, moved to East Germany. Gorbachev was infuriated, he objected, but he was informed by the United States that this was only a verbal agreement, there was nothing on paper. So, too bad. [President Bill] Clinton came along and expanded NATO to the borders of Russia to, as Mearsheimer points out.

To the current threat to incorporate Ukraine into NATO, it’s a various serious threat that no Russian leader, whoever it is, could easily tolerate. It’s as if Mexico in the 1980s had overthrown the government, and the new government called for joining the Warsaw Pact. It’s inconceivable. So it’s a real problem. Not the whole problem, but part of it.

The Ukrainian parliament, as you know, recently overwhelmingly passed a resolution to move towards joining NATO. That’s pretty serious. Now there is — I think, anyone who thinks about it, including the negotiators on all sides, knows what a resolution ought to be. Ukraine ought to be neutralized, with a recognition on all sides that it won’t join any hostile military alliance. That’s perfectly feasible, even good for Ukraine. And then steps have to be taken to some kind of devolution of power. You can discuss exactly how much should be done, but the basic outlines are clear. That could be a partial resolution to the crisis, but, unfortunately, there are other voices.

RT: We saw, at the end of last year, without any consent of the United Nations, the US started operations in Syria on ISIS positions. Pretty much the same thing is happening right now in Yemen. Professor, would this mean that international law, as we’ve always known it, is pretty much dead, is pretty much gone, is not used and considered anymore ?

NC: To say that it’s dead implies it was ever alive. Has it ever been alive? Go back to, say, the 1980s. There were two resolutions brought to the UN security council calling on all states to observe international law. They both were vetoed by the United States with the support of Britain and France, its allies. Why? Because the hidden understanding, not expressed, was the intent was to call on the United States to accept the judgment of the world court, which condemned what it called the unlawful use of force by the United States against Nicaragua. It called on the United States to terminate the attack and pay enormous reparations. The US refused. Then came these two UN security council resolutions, which the US vetoed. That tells you what international law is, but we can go much beyond.

International law cannot be enforced against great powers. There’s no enforcement mechanism. Take a look at the International Criminal Court, who has investigated and sentenced African leaders who the US doesn’t like. The major crime of this millennium, certainly, is the US invasion of Iraq. Could that be brought to the international court? I mean, it’s beyond inconceivable. In fact, as you may know, there’s a law in the United States, passed by Congress and accepted by the president, which, in Europe, it’s called the Netherlands Invasion Act. It’s a law that authorizes the president to use force to rescue any American that might be brought to The Hague for trial. Does international law have anything to say about this? Well, it does. Actually international law has something to say about a standard comment made over and over again by Western leaders, by Obama and others, with regard to Iran: ‘All options are open.’ That includes attack, the kind of attack which is called for in the major press. There happens to be a UN charter, which, in Article II, bans the threat or use of force on international affairs. Does anybody care? No. International law is kind of like the United Nations. It can work up to the point where the great powers permit it. Beyond that, unfortunately, it can’t.

RT: Finally, the documentary about you which is about to premiere — called Requiem for an American Dream. Do you think the American dream is gone?

NC: It’s certainly declined. So the US has close to the lowest social mobility in the OECD [Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development] — you know, rich countries. If you look at OECD measures of social justice — accessibility to health care, obvious measures — the United States ranks near the bottom, I think right next to Turkey. These are serious attacks on what’s called the American dream. It’s still the richest and most powerful country in world, there are extraordinary advantages. In many respects, it’s the most free country in the world, as I’ve already mentioned.

So there’s plenty of positive aspects, but it’s a very serious decline. In fact, even American democracy — which is presented as a model to the world — is very remote from democracy. In fact, that’s one of the major topics of academic social-political science, the study of relation between public opinion and public policy, which is pretty easy to study. You see the policy, there’s extensive polling, you know what people’s opinions are. And basically most of the population is disenfranchised. Their representatives pay no attention to their opinion. That’s roughly the lowest three-quarters on the bottom of the income scale. Move up the scale, you get a little more influence. At the top, essentially policy is made. That’s plutocracy, not democracy.

Democracy functions formally: you’re free, I’m free, anyone’s free to express their opinions. I can vote any way I like in the coming election. If I feel like voting Green [Party], I can vote Green. There’s not going to be very much fraud, it’s mostly honest. So the formal trappings of democracy do exist, which is not a small point. But the functioning of democracy has very severely declined.

(From: RT)