Let Cuba breathe

If the objective of the US truly were democracy, engagement would be the more logical path.

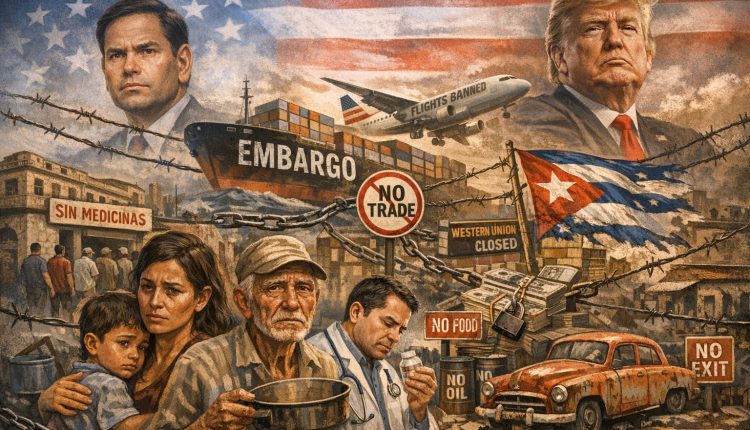

For more than six decades, Cuba has lived under the shadow of economic warfare imposed by the United States. What began as a Cold War strategy hardened into a permanent system of sanctions whose stated purpose, from the outset, was not merely to pressure a government but to break a society.

In April 1960, U.S. official Lester D. Mallory wrote in a secret memorandum that the goal of policy toward Cuba should be to deny the island money and supplies in order to reduce wages and “bring about hunger, desperation, and overthrow of government.” Rarely has the intent behind sanctions been expressed with such blunt clarity.

More than sixty years later, the architecture built from that premise has only grown. Trade embargoes, financial isolation, travel restrictions, bans on technology, limits on remittances, penalties on third countries, and pressure on international institutions together form one of the most comprehensive sanction regimes ever imposed on a small nation. It reaches into shipping lanes, banking systems, medicine supply chains, academic exchanges, and even family connections.

Whatever one’s view of the Cuban government, the reality is unavoidable: the principal victims of this policy are ordinary people. When a country cannot freely purchase fuel, spare parts, medical equipment, construction materials, or agricultural inputs, shortages are not theoretical — they are lived daily. Hospitals improvise. Infrastructure decays. Power outages multiply. Families wait in lines that stretch for hours.

Sanctions advocates often argue that hardship will produce political change. History suggests otherwise. External pressure tends to harden positions, empower security structures, and shift blame outward. Meanwhile, it deprives citizens of the very resources — information, mobility, economic independence — that foster pluralism and reform.

If the objective truly were democracy, engagement would be the more logical path. Trade exposes societies to new ideas. Travel builds human connections. Academic and cultural exchange nurtures civil institutions. Economic opportunity creates stakeholders in stability and openness. Isolation does the opposite.

Moreover, the policy places the United States in a contradictory moral position. Washington routinely champions free markets, sovereignty, and humanitarian values, yet maintains measures that restrict food, medicine, energy, and finance to a neighboring country of eleven million people. Such pressure on a small island is more a demonstration of insecurity than of strength.

Ending this posture would not be a concession to any government; it would be an affirmation of a principle: that nations should be allowed to solve their own problems without coercion that produces suffering. Cuba’s future — its political system, economy, and social contract — should be determined by Cubans, not engineered through external deprivation.

After sixty years, one conclusion is clear. The policy has not achieved its stated goals. It has, however, inflicted measurable human cost and entrenched mutual distrust.

A different approach is long overdue. Replace punishment with engagement. Replace intimidation with dialogue. Replace economic asphyxiation with normal relations.

Let Cuba breathe — and let its people decide their own destiny.