Oppenheimer paradox: Power of science and the weakness of scientists (+Español)

By Prabir Purkayastha

I remember my first encounter with American guilt over the two atom bombs dropped on Japan. I was attending a conference on distributed computer controls in Monterey, California, in 1985, and our hosts were the Lawrence Livermore Laboratories. This was the weapons laboratory that had developed the hydrogen bomb. During dinner, the wife of one of the nuclear scientists asked the Japanese professor at the table if the Japanese understood why the Americans had to drop the bomb on Japan. That it saved a million lives of American soldiers? And many more Japanese? Was she looking for absolution for the guilt that all Americans carried? Or was she seeking confirmation that what she had been told and believed was the truth? That this belief was shared even by the victims of the bomb?

This is not about the Oppenheimer film; I am only using it as a peg to talk about why the atomic bomb represented multiple ruptures in society. Not just at the level of war, where this new weapon changed the parameters of war completely. But also the recognition in society that science was no longer the concern of the scientists alone but of all of us. For scientists, it also became a question that what they did in the laboratories had real-world consequences, including the possible destruction of humanity itself. It also brought home that this was a new era, the era of big science that needed mega bucks!

Strangely enough, two of the foremost names of scientists at the core of the anti-nuclear bomb movement after the war also had a major role in initiating the Manhattan Project. Leo Szilard, a Hungarian scientist who had become a refugee in England first and then in the United States, sought Einstein’s help in petitioning President Roosevelt for the United States to build the bomb. He was afraid that if Nazi Germany built it first, it would conquer the world. Szilard joined the Manhattan Project, though he was located not in Los Alamos but in the University of Chicago’s Metallurgical Laboratories. Szilard also campaigned within the Manhattan Project for a demonstration of the bomb before its use on Japan. Einstein also tried to reach President Roosevelt with his appeal against the use of the bomb. But Roosevelt died, with Einstein’s letter unopened on his desk. He was replaced by Vice-President Truman, who thought that the bomb would give the United States a nuclear monopoly, therefore, help subjugate the Soviet Union in the post-War scenario.

Turning to the Manhattan Project. It is the scale of the project that was staggering, even by today’s standards. At its peak, it had employed 125,000 people directly, and if we include the many other industries who were either directly or indirectly produced parts or equipment for the bomb, the number would be close to half a million. The costs again were huge, $2 billion in 1945 (around $30-50 billion today). The scientists were an elite group that included Hans Bethe, Enrico Fermi, Nils Bohr, James Franck, Oppenheimer, Edward Teller (the villain of the story later), Richard Feynman, Harold Urey, Klaus Fuchs (who shared atomic secrets with the Soviets) and many more glittering names. More than two dozen Nobel prize winners were associated with the Manhattan Project in various capacities.

But science was only a small part of the project. The Manhattan Project wanted to build two kinds of bombs: one using uranium 235 isotope and the other plutonium. How do we separate fissile material, U 235, from U 238? How do we concentrate weapons grade plutonium? How to do both at an industrial scale? How do we set up the chain reaction to create fission, bringing sub-critical fissile material together to create a critical mass? All these required metallurgists, chemists, engineers, explosive experts, and the fabrication of completely new plants and equipment spread over hundreds of sites. All of it is to be done at record speeds. This was a science “experiment” being done, not at a laboratory scale, but on an industrial scale. That is why the huge budget and the size of the human power involved.

The U.S. government convinced their citizens that Hiroshima, and three days after that, the Nagasaki bombings led to the surrender of Japan. Based on archival and other evidence, it is clear that more than the nuclear bombs, the Soviet Union declaring war against Japan was what led to its surrender. They have also shown that the number of “one million American lives saved” due to Hiroshima and Nagasaki, as it avoided an invasion of Japan, had no basis. It was a number created entirely for propaganda purposes.

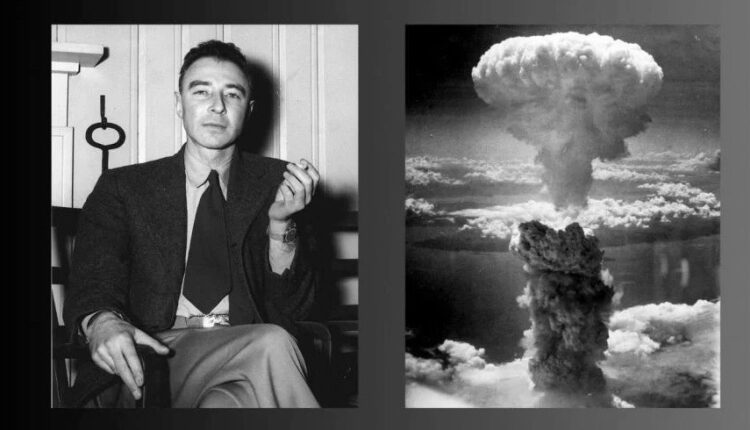

While the American people were given these figures as serious calculations, what was completely censored were the actual pictures of the victims of the two bombs. The only picture available of the Hiroshima bombing—the mushroom cloud—was the one taken by the gunner of Enola Gay. Even when a few photographs of Hiroshima and Nagasaki were released months after the nuclear bombings, they were only of shattered buildings, none of actual human beings.

The United States, basking in their victory over Japan, did not want it to be marred by the visuals of the horror of the nuclear bomb. The United States dismissed people dying of a mysterious disease, what the United States knew was radiation sickness, as propaganda by the Japanese. To quote General Leslie Groves who led the Manhattan Project, these were “Tokyo Tales”. It took seven years for the human toll to be visible, and only after the United States ceased its occupation of Japan. Even this was only a few pictures, as Japan was still cooperating with the United States in the hushing up of the horror of the nuclear bomb. The full visual account of what happened in Hiroshima had to wait till the sixties: the pictures of people vaporized leaving only an image on the stone on which they were sitting, survivors with skin hanging from their bodies, people dying of radiation sickness.

The other part of the nuclear bomb was the role of the scientists. They became the heroes who had shortened the war and saved one million American lives. In this myth making, the nuclear bomb was converted from a major industrial scale effort to a secret formula discovered by a few physicists which gave the United States enormous power in the Post War era. This was what made Oppenheimer a hero for the American people. He symbolized the scientific community and its godlike powers. And also the target for people like Teller, who later on combined with others to bring Oppenheimer down.

But if Oppenheimer was a hero just a few years back, how did they succeed in pulling him down?

It is difficult to imagine that the United States had a strong left movement before the 2nd World War. Apart from the presence of the communists in the workers movements, the world of the intelligentsia— literature, cinema and the physicists—also had a strong communist presence. As can be seen in the Oppenheimer film. The idea that science and technology can be planned as Bernal was arguing in the UK, and should be used for public good was what the scientists had embraced. That is why the physicists, at that time at the forefront of the cutting edge in sciences—relativity, quantum mechanics—were also at the forefront of the social and political debates in science and on science.

It is this world of science, a critical worldview collided with the new world where the United States should be the exceptional nation and the sole global hegemon. Any weakening of this hegemony could only happen because some people, traitors to this nation, gave away “our” national secrets. Any development anywhere else could be only a result of theft, and nothing else. This campaign was also helped due to the belief that the atom bomb was the result of a few equations that scientists had discovered and could therefore be easily leaked to enemies.

This was the genesis of the McCarthy era, a war on the U.S. artistic, academic and the scientific community. For a search for spies under the bed. The military industrial complex was being born in the United States and soon took over the scientific establishment. It was the military and the energy—nuclear energy—budget that would henceforth determine the fate of scientists and their grants. Oppenheimer needed to be punished as an example to others. The scientists should not set themselves up against the gods of the military industrial complex and their vision of world domination.

Oppenheimer’s fall from grace served another purpose. It was a lesson to the scientific community that if it crossed the security state, no one was big enough. Even though Rosenbergs—Julius and Ethel—were executed they were relatively minor figures. Julius had not leaked any atomic secrets, only kept the Soviet Union abreast of the developments. Ethel, though a communist, had nothing to do with any spying. The only person who did leak atomic “secrets” was Klaus Fuchs, a German communist party member, who escaped to the UK, worked in the bomb project first in the UK and then in the Manhattan project as a part of the British team there. He made important contributions to the nuclear bomb triggering mechanism and shared these with the Soviet Union. Fuchs’ contribution would have shortened the Soviet bomb by possibly a year. As a whole host of nations have shown, once we know a fissile bomb is possible, it is easy for scientists and technologists to duplicate it. As has been done by countries as small as North Korea.

The Oppenheimer tragedy was not that he was victimized in the McCarthy era and lost his security clearance. Einstein never had security clearance, so that need not have been a major calamity for him either. It was his public humiliation during the hearings when he challenged the withdrawal of his security clearance that broke him. The physicists, the golden boys of the atomic era, had finally been shown their true place in the emerging world of the military industrial complex.

Einstein, Szilard, Rotblatt and others had foreseen this world. They, unlike Oppenheimer, took to the path of building a movement against the nuclear bomb. The scientists, having built the bomb, had to now act as conscience keepers of the world, against a bomb that can destroy all humanity. The bomb that still hangs as a Damocles sword over our heads.

Prabir Purkayastha is the founding editor of Newsclick.in, a digital media platform. He is an activist for science and the free software movement. This article was produced in partnership by Newsclick and Globetrotter.

*****

Versión en Español:

Paradoja de Oppenheimer: el poder de la ciencia y la debilidad de los científicos

Recuerdo mi primer encuentro con la culpa estadounidense por las dos bombas atómicas lanzadas sobre Japón. Yo asistía a una conferencia sobre controles informáticos distribuidos en Monterey, California, en 1985, y nuestros anfitriones eran los Laboratorios Lawrence Livermore. Este era el laboratorio de armas que había desarrollado la bomba de hidrógeno. Durante la cena, la esposa de uno de los científicos nucleares preguntó al profesor japonés sentado a la mesa si los japoneses entendían por qué los estadounidenses tuvieron que lanzar la bomba sobre Japón. ¿Que salvó un millón de vidas de soldados americanos? ¿Y muchos más japoneses? ¿Buscaba la absolución de la culpa que cargaban todos los estadounidenses? ¿O buscaba confirmación de que lo que le habían dicho y creía era la verdad? ¿Que esta creencia era compartida incluso por las víctimas de la bomba?

No se trata de la película de Oppenheimer; Sólo lo uso como referencia para hablar de por qué la bomba atómica representó múltiples rupturas en la sociedad. No sólo a nivel de la guerra, donde esta nueva arma cambió completamente los parámetros de la guerra. Pero también el reconocimiento en la sociedad de que la ciencia ya no era asunto sólo de los científicos sino de todos nosotros. Para los científicos, también se convirtió en una cuestión de que lo que hacían en los laboratorios tuviera consecuencias en el mundo real, incluida la posible destrucción de la propia humanidad. También me hizo comprender que ésta era una nueva era, ¡la era de la gran ciencia que necesitaba mucho dinero!

Por extraño que parezca, dos de los nombres más destacados de los científicos que estuvieron en el centro del movimiento antibombas nucleares después de la guerra también tuvieron un papel importante en el inicio del Proyecto Manhattan. Leo Szilard, un científico húngaro que se había convertido en refugiado primero en Inglaterra y luego en Estados Unidos, buscó la ayuda de Einstein para solicitar al presidente Roosevelt que Estados Unidos construyera la bomba. Tenía miedo de que, si la Alemania nazi lo construía primero, conquistaría el mundo. Szilard se unió al Proyecto Manhattan, aunque no estaba ubicado en Los Álamos sino en los Laboratorios Metalúrgicos de la Universidad de Chicago. Szilard también hizo campaña dentro del Proyecto Manhattan para una demostración de la bomba antes de su uso en Japón. Einstein también intentó llegar al presidente Roosevelt con su llamamiento contra el uso de la bomba. Pero Roosevelt murió, con la carta de Einstein sin abrir sobre su escritorio. Fue reemplazado por el vicepresidente Truman, quien pensó que la bomba daría a Estados Unidos un monopolio nuclear y, por tanto, ayudaría a subyugar a la Unión Soviética en el escenario de la posguerra.

Pasando al Proyecto Manhattan. Es la escala del proyecto lo que fue asombroso, incluso para los estándares actuales. En su apogeo, había empleado directamente a 125.000 personas, y si incluimos las muchas otras industrias que directa o indirectamente producían piezas o equipos para la bomba, la cifra se acercaría al medio millón. Los costos nuevamente fueron enormes: 2 mil millones de dólares en 1945 (entre 30 y 50 mil millones de dólares en la actualidad). Los científicos eran un grupo de élite que incluía a Hans Bethe, Enrico Fermi, Nils Bohr, James Franck, Oppenheimer, Edward Teller (el villano de la historia posterior), Richard Feynman, Harold Urey, Klaus Fuchs (que compartió secretos atómicos con los soviéticos). y muchos más nombres brillantes. Más de dos docenas de premios Nobel estuvieron asociados con el Proyecto Manhattan en diversas capacidades.

Pero la ciencia era sólo una pequeña parte del proyecto. El Proyecto Manhattan quería construir dos tipos de bombas: una con isótopo de uranio 235 y otra con plutonio. ¿Cómo separamos el material fisible, U 235, del U 238? ¿Cómo concentramos el plutonio apto para armas? ¿Cómo hacer ambas cosas a escala industrial? ¿Cómo configuramos la reacción en cadena para crear fisión, reuniendo material fisionable subcrítico para crear una masa crítica? Todo esto requirió metalúrgicos, químicos, ingenieros, expertos en explosivos y la fabricación de plantas y equipos completamente nuevos repartidos en cientos de sitios. Todo esto debe hacerse a velocidades récord. Se trataba de un “experimento” científico que se estaba realizando, no a escala de laboratorio, sino a escala industrial. De ahí el enorme presupuesto y la magnitud del poder humano involucrado.

El gobierno de Estados Unidos convenció a sus ciudadanos de que Hiroshima y, tres días después, los bombardeos de Nagasaki condujeron a la rendición de Japón. Con base en evidencia de archivo y de otro tipo, está claro que más que las bombas nucleares, la declaración de guerra de la Unión Soviética contra Japón fue lo que llevó a su rendición. También han demostrado que la cifra de “un millón de vidas estadounidenses salvadas” gracias a Hiroshima y Nagasaki, que evitaron una invasión de Japón, no tenía fundamento. Era un número creado íntegramente con fines propagandísticos.

Mientras que al pueblo estadounidense se le presentaron estas cifras como cálculos serios, lo que fue completamente censurado fueron las fotografías reales de las víctimas de las dos bombas. La única fotografía disponible del bombardeo de Hiroshima (la nube en forma de hongo) fue la tomada por el artillero del Enola Gay. Incluso cuando se publicaron algunas fotografías de Hiroshima y Nagasaki meses después de los bombardeos nucleares, sólo se trataba de edificios destrozados, ninguna de seres humanos reales.

Estados Unidos, disfrutando de su victoria sobre Japón, no quería que se viera empañada por las imágenes del horror de la bomba nuclear. Estados Unidos desestimó a las personas que morían de una enfermedad misteriosa, lo que sabían que era enfermedad por radiación, como propaganda de los japoneses. Para citar al general Leslie Groves, que dirigió el Proyecto Manhattan, se trataba de “Cuentos de Tokio”. Fueron necesarios siete años para que el costo humano fuera visible, y sólo después de que Estados Unidos cesara su ocupación de Japón. Incluso estas son sólo algunas imágenes, ya que Japón todavía coopera con los Estados Unidos para silenciar el horror de la bomba nuclear. El relato visual completo de lo ocurrido en Hiroshima tuvo que esperar hasta los años sesenta: las imágenes de personas vaporizadas dejando sólo una imagen en la piedra sobre la que estaban sentados, supervivientes con la piel colgando del cuerpo, personas muriendo por enfermedades causadas por la radiación.

La otra parte de la bomba nuclear fue el papel de los científicos. Se convirtieron en los héroes que acortaron la guerra y salvaron un millón de vidas estadounidenses. En esta creación de mitos, la bomba nuclear pasó de ser un gran esfuerzo a escala industrial a una fórmula secreta descubierta por unos pocos físicos que dio a los Estados Unidos un enorme poder en la era de la posguerra. Esto fue lo que convirtió a Oppenheimer en un héroe para el pueblo estadounidense. Simbolizaba a la comunidad científica y sus poderes divinos. Y también el objetivo de gente como Teller, que más tarde se combinó con otros para derribar a Oppenheimer.

Pero si Oppenheimer era un héroe hace apenas unos años, ¿cómo lograron derribarlo?

Es difícil imaginar que Estados Unidos tuviera un fuerte movimiento de izquierda antes de la Segunda Guerra Mundial. Aparte de la presencia de los comunistas en los movimientos obreros, el mundo de la intelectualidad (la literatura, el cine y los físicos) también tuvo una fuerte presencia comunista. Como se puede ver en la película de Oppenheimer. Los científicos habían adoptado la idea de que la ciencia y la tecnología pueden planificarse, como argumentaba Bernal en el Reino Unido, y deberían utilizarse para el bien público. Por eso los físicos, que en aquel momento estaban a la vanguardia de las ciencias más avanzadas (la relatividad, la mecánica cuántica), también estaban a la vanguardia de los debates sociales y políticos sobre la ciencia y sobre la ciencia.

Es este mundo de la ciencia, una visión crítica del mundo que choca con el nuevo mundo donde Estados Unidos debería ser la nación excepcional y la única potencia hegemónica global. Cualquier debilitamiento de esta hegemonía sólo podría ocurrir porque algunas personas, traidores a esta nación, revelaron “nuestros” secretos nacionales. Cualquier acontecimiento en cualquier otro lugar podría ser sólo el resultado de un robo y nada más. Esta campaña también se vio favorecida por la creencia de que la bomba atómica era el resultado de algunas ecuaciones que los científicos habían descubierto y, por lo tanto, podía filtrarse fácilmente a los enemigos.

Esta fue la génesis de la era McCarthy, una guerra contra la comunidad artística, académica y científica de Estados Unidos. Para buscar espías debajo de la cama. El complejo industrial militar estaba naciendo en Estados Unidos y pronto se apoderó del establishment científico. Fueron el presupuesto militar y el de energía (energía nuclear) los que en adelante determinarían el destino de los científicos y sus subvenciones. Oppenheimer necesitaba ser castigado como ejemplo para los demás. Los científicos no deberían oponerse a los dioses del complejo industrial militar y su visión de dominación mundial.

La caída en desgracia de Oppenheimer sirvió para otro propósito. Fue una lección para la comunidad científica de que si cruzaban el estado de seguridad, nadie era lo suficientemente grande. Aunque los Rosenberg (Julius y Ethel) fueron ejecutados, eran figuras relativamente menores. Julius no había filtrado ningún secreto atómico, sólo mantuvo a la Unión Soviética al tanto de los acontecimientos. Ethel, aunque comunista, no tuvo nada que ver con ningún espionaje. La única persona que filtró “secretos” atómicos fue Klaus Fuchs, un miembro del partido comunista alemán, que escapó al Reino Unido, trabajó en el proyecto de la bomba primero en el Reino Unido y luego en el proyecto de Manhattan como parte del equipo británico allí. Hizo importantes contribuciones al mecanismo de activación de la bomba nuclear y las compartió con la Unión Soviética. La contribución de Fuchs habría acortado la duración de la bomba soviética posiblemente en un año. Como lo han demostrado una gran cantidad de naciones, una vez que sabemos que una bomba fisionable es posible, es fácil para los científicos y tecnólogos duplicarla. Como lo han hecho países tan pequeños como Corea del Norte.

La tragedia de Oppenheimer no fue que fuera víctima de la era McCarthy y perdiera su autorización de seguridad. Einstein nunca tuvo autorización de seguridad, por lo que tampoco tuvo por qué haber sido una gran calamidad para él. Fue su humillación pública durante las audiencias cuando impugnó la retirada de su autorización de seguridad lo que lo quebró. A los físicos, los chicos de oro de la era atómica, finalmente se les había mostrado su verdadero lugar en el mundo emergente del complejo industrial militar.

Einstein, Szilard, Rotblatt y otros habían previsto este mundo. Ellos, a diferencia de Oppenheimer, tomaron el camino de construir un movimiento contra la bomba nuclear. Los científicos que construyeron la bomba tenían que actuar ahora como guardianes de la conciencia del mundo contra una bomba que puede destruir a toda la humanidad. La bomba que aún pende como una espada de Damocles sobre nuestras cabezas.