Experts warn Florida tower disaster is climate emergency ‘wake up call’

From Common Dreams

In the search for answers following last week’s disintegration of a high-rise condominium tower near Miami, some experts are cautiously pointing to the climate emergency as a possible culprit—or at the very least a risk multiplier in the disaster—underscoring the need for urgent climate and infrastructure action.

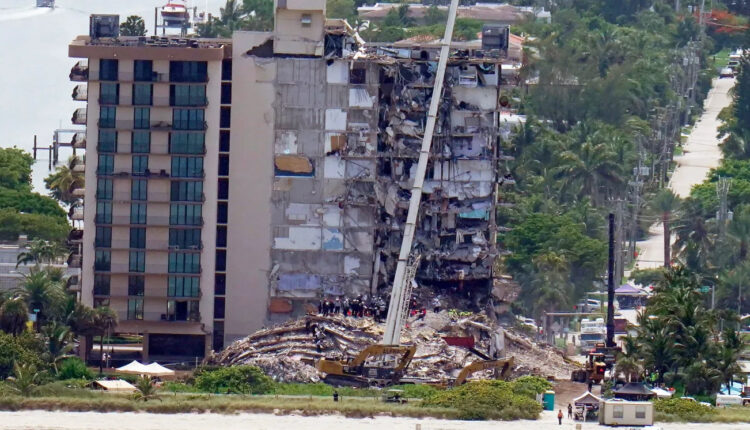

With 16 confirmed deaths and 150 people still missing following the partial collapse of Champlain Towers South in Surfside on June 24, rescuing survivors and retrieving victims’ bodies remains authorities’ top priority. However, officials and experts have also begun the long and daunting task of determining what caused the building to fail.

A 2018 engineering report on the 12-story tower noted design flaws and “major structural damage,” including a deteriorating roof, defective waterproofing, and crumbling concrete columns and rusting rebar in the building’s underground garage. The report warned that some of these problems could cause “exponential damage” in the future.

With so much well-documented existing damage, and with repairs to the building underway at the time it disintegrated, experts have been reluctant to attribute the collapse to any single cause.

However, numerous scientists and other experts say that rising sea levels and more intense tidal flooding related to the climate emergency could have played a significant role in the disaster.

There is little doubt among experts that a warming planet due to human activity is causing sea levels to rise, and it is certain that rising waters can infiltrate the porous limestone upon which southeastern Florida buildings stand, potentially degrading their foundations over time.

As a 5.9-inch rise in local sea levels and 320% surge in nuisance flooding in the area since the mid-1990s attests, metro Miami is particularly susceptible to the consequences of the climate emergency. Last year, a report (pdf) from Resources for the Future, a Washington, D.C.-based think tank, stated that Miami is “one of the most at-risk cities in the world from the damages caused by coastal flooding and storms.”

Atorod Azizinamini, who directs the Moss School of Construction, Infrastructure, and Sustainability at Florida International University (FIU), toldThe Palm Beach Post that “climate change can play a role” in disasters like the Champlain Towers South collapse. “It can cause settlement of the ground with sea level rise, and corrosion.” Zhong-Ren Peng, director of the International Center for Adaptation Planning and Design at the University of Florida, told The Palm Beach Post that “sea level rise does cause potential corrosion and if that was happening, it’s possible it could not handle the weight of the building.”

Zhong-Ren Peng, director of the International Center for Adaptation Planning and Design at the University of Florida, told The Palm Beach Post that “sea level rise does cause potential corrosion and if that was happening, it’s possible it could not handle the weight of the building.”

“I think this could be a wake-up call for coastal developments,” warned Peng.

Albert Slap, chief executive of the Boca Raton, Florida-based construction risk assessment company RiskFootprint, explained to The Washington Post that “groundwater enters the pores of the concrete and ultimately weakens it and erodes it. So the foundations are subject to a lot of geological forces that could compact the soil underneath. It could cause voids. We just don’t know.”

Slap said the Champlain Towers South disaster “could be a canary-in-the-coal-mine-type event.”

“It’s not just one building,” he added. “This could be something that could affect other buildings.” Climate scientists predict (pdf) an acceleration in sea level rise in southeastern Florida, with a projected increase of 10 to 17 inches by 2040, 21 to 54 inches by 2070, and 40 to 136 inches by 2120.

Climate scientists predict (pdf) an acceleration in sea level rise in southeastern Florida, with a projected increase of 10 to 17 inches by 2040, 21 to 54 inches by 2070, and 40 to 136 inches by 2120.

Land subsidence—the sudden sinking or gradual settling of the ground’s surface—is also linked to the climate emergency. Shimon Wdowinski, a professor at Florida International University’s Institute of Environment, said an analysis of space-based radar data revealed signs of such subsidence at the site of the tower disaster in the 1990s.

“We reported about two millimeters per year over a period of six years so that comes to about 12 millimeters, about half an inch, or about the width of your finger,” Wdowinski told The Weather Channel. “So small things and slow processes can accumulate if you give them enough time.”

Separately, Wdowinski said that “when we measure subsidence or when we see movement of the buildings, it’s worth checking why it happens.”

“We cannot say what is the reason for that from the satellite images but we can say there was movement here,” he added.

Like many cities around the world, Miami is taking steps in an effort to mitigate the effects of rising seas and sinking land. According to Miami’s Stormwater Master Plan, installing a system of pumps, drainage, and sea walls would cost approximately $4 billion and still leave some areas without adequate protection.

However, experts warn that only urgent, transformational action can avert worst-case climate scenarios, and that attempting to merely treat the symptoms of the climate emergency with measures like sea walls will ultimately fail.

In a 2019 Popula article, essayist Sarah Miller wrote that “since Miami is built on limestone, which soaks up water like a sponge, walls are not very useful. In Miami, sea water will just go under a wall, like a salty ghost. It will come up through the pipes and seep up around the manholes. It will soak into the sand and find its way into caves and get under the water table and push the ground water up.”

“So while walls might keep the clogs of Holland dry, they cannot offer similar protection to the stilettos of Miami Beach,” she added.

Harold Wanless, a geologist and sea level rise expert at the University of Miami, told The Guardian that “every sandy barrier island, every low-lying coast, from Miami to Mumbai, will become inundated and [it will be] difficult to maintain functional infrastructure.”

“You can put valves in sewers and put in sea walls but the problem is the water will keep coming up through the limestone,” said Wanless. “You’re not going to stop this.”