UN unveils memorial to millions who were killed in slave trade

Visitors to the United Nations headquarters in New York will get a powerful reminder of the brutality of the transatlantic slave trade and its enormous impact on world history through a visually stunning new memorial that was unveiled yesterday in a solemn ceremony.

There were speeches intended to touch the emotionality of a system that operated for hundreds of years, killing an estimated 15 million African men, women and children and sending millions more into the jaws of a vicious system of plantation slavery in the Americas.

U.N. Secretary General Ban Ki-moon called slavery “a stain on human history.”

U.N. General Assembly President Sam Kutesa said slavery remained one of the “darkest and most abhorrent chapters” in world history.

It was only fitting that the ceremony take place at a site surrounded by the looming skyscrapers of New York. Slavery was the economic engine upon which American capitalism was built, providing the seed money for United States businesses to create the most vibrant economic system in the world. The enslaved Black person (whose gender is purposely vague to represent men, women and children) lying inside the dramatically shaped marble memorial, which is called The Ark of Return, is a symbol of the millions whose deaths led to the building of those skyscrapers, the visual emblems of American capitalism’s enormous financial windfall for the white beneficiaries of slavery and their descendants.

During his speech unveiling the memorial, Ban Ki-moon spoke directly to Black people in the Americas and the Caribbean who are descended from the enslaved Black people who were sacrificed.

“I hope descendants of the transatlantic slave trade will feel empowered as they remember those who overcame this brutal system and passed their rich cultural heritage from Africa on to their children,” Ban said.

In his remarks, he singled out Black women in particular, noting that a third of those Black people who were sold as slaves from Africa were female.

“In addition to enduring the harsh conditions of forced labor as slaves, they experienced extreme forms of discrimination and exploitation as a result of their gender,” he said.

The U.N. has declared 2015-2024 as the International Decade for People of African Descent. Kutesa said yesterday that The Ark of Return would be one of the most important contributions of the entire decade.

“The majority of the victims of this brutal, primitive trade in human beings remain unnamed and unknown. Nevertheless, their dignity and courage was boundless and worthy of this honor and tribute,” Kutesa said. “While this may be a solemn occasion, it is also an opportunity to celebrate the legacy of those unknown and unnamed enslaved Africans and honor their proud contribution to our societies, our institutions and our world.”

The memorial project was conceived more than five years ago by a group of African and Caribbean nations, led by Jamaica. Courtenay Rattray, the Permanent Representative of Jamaica, who also served as chair of the Permanent Memorial Committee, noted yesterday that several nations, along with UNESCO, helped raise more than $1.7 million to pay for it.

The 15-member Caribbean Community at the U.N. is in the midst of pursuing reparations claims against European nations that engaged in the slave trade. While Jamaica Prime Minister Portia Simpson Miller didn’t mention the reparations issue in her remarks yesterday, she did speak of slavery’s enduring legacy, noting that even after Britain passed a law on March 25, 1807, abolishing the slave trade, the institution persisted.

“For us freedom came after a long journey,” she said. “Freedom was not gifted to us but rather earned by the sweat, blood, and tears of millions of our forebears on whose back the economic foundations of the New World was built.”

The memorial was designed by Rodney Leon, an American architect of Haitian descent who was chosen two years ago after an international competition that attracted 310 entries from 83 countries. Leon was also the designer of the African Burial Ground National Monument in lower Manhattan, which was built on a spot where 15,000 people of African descent were buried over a period of around 100 years from the 1690s until 1794.

“It makes me feel extremely proud that I can play a role and a part in the commemoration of such an important and historic day,” Leon said during an interview yesterday. “I feel really proud that we have a physical marker and a place of remembrance for this annual celebration to take place moving forward.”

As the son of Haitian immigrants, Leon said his parents filled him with the history of Haitian liberation and the country’s struggle to be the first independent African state in the western hemisphere.

“My parents were always able to communicate to us as a family in terms of our history and our culture,” he said. “And I think that that plays a role in my being extremely proud of our Haitian and our African heritage. And as a result, when we have these legacies and these opportunities I think I tend to gravitate towards them.”

“We felt it was very important for us to counteract that experience and pay homage to their legacy,” Leon said.

In a profile of the work on the U.N. website, Leon talked about the process of creating it. He said his team consisted of professionals from around the world—other architects as well as structural, mechanical, electrical and plumbing engineers, sculptors, steel workers, lighting designers and people with expertise in building water features. They came from the Caribbean, Africa, as well as Europe.

“We were also interested in the idea of the slave ships and these vessels that carried people through tragic conditions to the new world,” he said. “So we felt it would be a good counterpoint to establish a spiritual space of return, an ‘Ark of Return,’ a vessel where we can begin to create a counter-narrative and undo some of that experience.”

Leon said he designed the monument so that it could be touched—by members of the public but also by dignitaries at the UN, reminding them, as they deal with global issues on a daily basis, of mistakes made in the past.

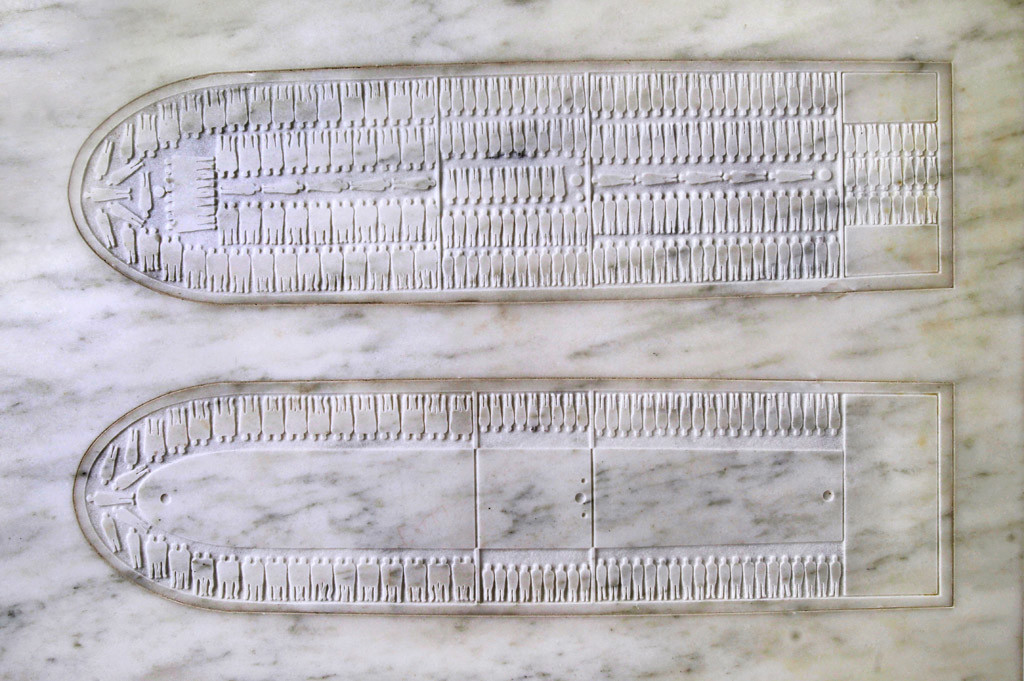

The memorial is etched with drawings of actual slave ships, depicting cross-sections of vessels and showing their systematic organization in order to pack in as much “human cargo” as possible.

“We felt that that experience was very much something that needed to be visually described,” he said, referring to the human forms, stacked horizontally in three levels, barely able to sit-up. “I think they lost at least 15 percent or more of the ‘cargo’ on a typical slave journey.”

Of the figure laying prone inside the sculpture, he said it is a deliberately androgynous human sculpture, called ‘the trinity figure,’ representing the human spirit and the spirit of the men, women and children of African descent whose deaths resulted from the slave trade.

“A lot of people had to suffer in very confined quarters,” he said. “And the reason why it kind of seems like it’s androgynous, it’s sort of meant to represent those three elements – men, women and children. You’re sort of not really supposed to be able to tell.”

He said the figure’s leg, hand and face are made from black Zimbabwean granite.

“It has an outreached hand that’s meant to kind of reach out to people that are coming in,” he said. “It features a kind of tear that comes out of the face. That tear is supposed to wash down the side of the face and sets up the third element in the project.”

That third element is a triangular waterfall, created by the tears that flow from the face of the ‘trinity statue’ into two triangular reflecting pools. Leon said this element, located outside of the memorial, is intended to look ahead to the future.

“It’s really about dealing with our current conditions of contemporary slavery and how that actually is something we need to be fighting today,” he said. “It’s about acknowledging that condition and thinking about future generations and educating future generations so this tragedy doesn’t happen again in the future. So that’s why it’s pointing the way forward for us after you’ve passed through.”

Leon said the idea that children will be interacting and learning from his work “actually brings me ongoing joy.”

(From: Atlanta Blackstar)