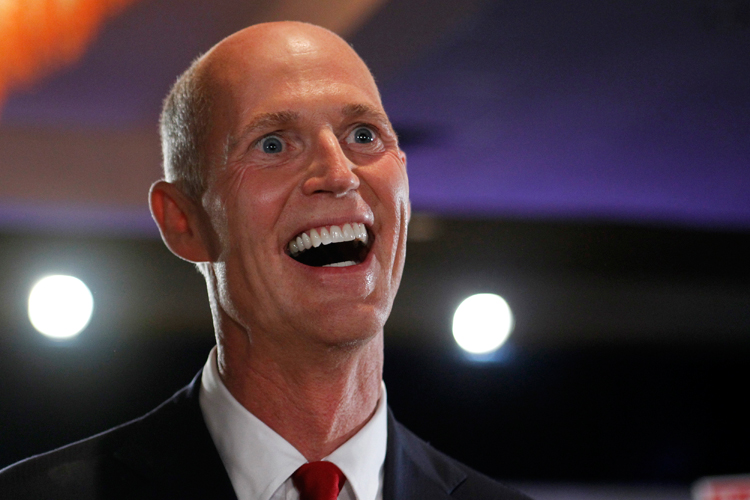

To avoid conflicts, Rick Scott created a trust blind in name only

By Kevin Sack and Patricia Mazzei

TALLAHASSEE, Fla. — Rick Scott had been governor of Florida for barely three months when questions first mounted about conflicts of interest. Fabulously wealthy but a newcomer to politics, Mr. Scott mandated random drug testing for state workers in March 2011, and was pushing the legislature to require it for welfare recipients. The Republican governor, who had made his fortune as a health care executive and investor, also proposed reorienting the state’s Medicaid system toward managed care.

As it happened, those moves would have created vast potential markets for the chain of 32 urgent-care clinics that Mr. Scott had co-founded a decade earlier, after his forced resignation as chief executive of the hospital company Columbia/HCA. News reports about the governor’s personal stake in the Solantic clinics, which he transferred to his wife shortly before taking office, stifled the momentum of his first months in office.

To shield himself from future conflict charges, Mr. Scott, who is now running to unseat the incumbent senator Bill Nelson, created a $73.8 million investment account that he called a blind trust. But an examination of Mr. Scott’s finances shows that his trust has been blind in name only. There have been numerous ways for him to have knowledge about his holdings: Among other things, he transferred many assets to his wife and neither “blinded” nor disclosed them. And their investments have included corporations, partnerships and funds that stood to benefit from his administration’s actions.

Only in late July, when compelled by ethics rules for Senate candidates, did Mr. Scott disclose his wife’s holdings. That report revealed that his wife, Ann Scott, an interior decorator by trade, controlled accounts that might exceed the value of her husband’s. Their equity investments largely mirrored each other, meaning that Mr. Scott could, if he wanted, track his own holdings by following his wife’s.

The filing revealed that the Scotts together were worth between $254.3 million and $510 million. (The Senate requires that assets be valued only in ranges.) They own a beachfront mansion in Naples, Fla., valued at $14.1 million (along with a $147,000 boathouse) and a Montana residence on 61 acres worth $1.5 million. The governor, who has banked more than $200 million in investment income while in office, forgoes his $130,000 state salary and jets across Florida in his own plane.

If he wins a tight race for the Florida seat, which is central to control of the Senate, Mr. Scott could well become the richest member of the next Congress. His broad menu of investments might regularly present conflicts that require recusal. He has declined to say whether he would use a blind trust in the Senate, where the rules controlling them are far more stringent.

Mr. Nelson, a 76-year-old Democrat who is serving his third term, has made campaign issues of Mr. Scott’s wealth and the blindness of his trust. “Governor Scott has been in public service for himself,” he charged in August.

Mr. Nelson’s net worth is between $608,000 and $4.7 million, with his largest holdings in undeveloped real estate in his home county, according to his most recent disclosures. The Scott campaign has stretched to highlight Mr. Nelson’s investment in a mutual fund that includes holdings in a Russian bank placed under American sanctions and a Chinese telecommunications company considered a possible national security risk. But Mr. Nelson’s stake in the fund is small, less than $15,000, and those companies together comprise only 3 percent of its inventory.

Mr. Scott declined to be interviewed for this article. But in a statement provided by his campaign, he said, “I have never made a single decision as governor with any thought or consideration of my personal finances.” He added, “I will not apologize for having success in business.”

Mr. Scott’s case demonstrates the political complexities of campaigning while rich, a hallmark of the age of the first billionaire president. The median net worth of members of Congress has increased in the past decade, particularly in the Senate. That matters because of the ability to self-fund ever more expensive campaigns.

Between 2000 and 2016, there were 38 congressional campaigns in which candidates invested at least $5 million of their own money, and 227 in which they invested at least $1 million, according to the Center for Responsive Politics. President Trump set a record for federal candidates in 2016 by spending $66.1 million. This year, J. B. Pritzker, the billionaire Democrat running for governor of Illinois, has already contributed a record $146.5 million to his own campaign, according to a September disclosure.

Mr. Scott, 65, who faces term limits as governor, has shown a willingness to devote whatever it takes to win, sometimes with late infusions that blindside the opposition. The Scotts put more than $70 million into his first race for governor, which he won by a percentage point, and spent $12.8 million more to win re-election in 2014, again by one point.

For his Senate effort, Mr. Scott has given himself $38.9 million as of mid-October, accounting for 72 percent of all contributions to his campaign (compared with $310 in self-funding by Mr. Nelson). That has enabled Mr. Scott to outspend Mr. Nelson by more than two to one, and helped make the Florida race one of the country’s most expensive congressional midterms.

Business before the state

Over the years, Mr. Scott and his press officers have relied on a package of terse talking points that dismiss the possibility of conflicts and stress the governor’s humble beginnings (he spent three childhood years in public housing). The blind trust, they assert, has kept Mr. Scott in the dark.

Yet the blindness of Mr. Scott’s trust has been challenged in a state lawsuit filed by a Tallahassee lawyer. And the governor’s apparent conflicts of interest have been scrutinized throughout his tenure.

Among the starkest examples are the Scotts’ investments in numerous companies and partnerships with ownership interests in each of Florida’s three primary natural gas pipelines, which are permitted and regulated by the state.

The Scotts have invested heavily in the energy sector, particularly with the advent of hydraulic fracturing. Holdings obtained by the blind trust include shares in two limited partnerships — NextEra Energy Partners and Spectra Energy Partners — that are affiliated with the operators of the newest pipeline, the Sabal Trail Transmission. This year’s disclosure shows that the trust held NextEra shares valued at up to $250,000, and that Mrs. Scott owns as much as $500,000.

The $3.2 billion construction of Sabal Trail through Alabama, Georgia and 12 Florida counties drew opposition from landowners, conservationists and clean-energy advocates. But it won an expedited state review through legislation supported by the governor in 2013, and then was approved by Mr. Scott’s appointees to the Public Service Commission and his Department of Environmental Protection.

The Scotts also invested in Gilead Sciences, a pharmaceutical company that in 2013 began marketing a highly effective and expensive drug named Sovaldi to treat hepatitis C, the liver-ravaging virus whose spread has been fueled by the opioid crisis. Mr. Scott owned $1.1 million in Gilead stock that year, according to disclosure reports.

Since then, Florida has spent millions in state Medicaid costs to cover Gilead’s hepatitis C drugs. Last year, a federal judge ruled that the state had failed to properly care for as many as 20,000 prison inmates suffering from the virus, forcing state lawmakers to spend $21.7 million on treatment this year.

This year’s disclosure shows that the Scotts have sold some Gilead stock, but that they still own shares worth up to $100,000 in one of Mrs. Scott’s trusts and up to $50,000 in a joint retirement account. They reported dividends and capital gains between $250,000 and $2.1 million from Gilead in 2017 and 2018.

Mr. Scott’s wealth accumulated from at least three major paydays across his career, starting with his 1997 ouster from Columbia/HCA with a $10 million severance package and stock and options worth up to $300 million. The giant health care corporation, which Mr. Scott helped found, had been implicated in a major federal Medicare fraud investigation, ultimately admitting to criminal wrongdoing and paying a record $1.7 billion in penalties. Mr. Scott was not charged.

In 2011, shortly before Mr. Scott formed his blind trust, his family sold its stake in Solantic, the chain of health clinics. Mr. Scott valued his investment at $62 million in 2009 but has said he sold it for less.

Then early last year, Mr. Scott and his family sold Continental Structural Plastics, a Michigan-based automotive supplier that they had controlled since 2005, to a Japanese conglomerate for $825 million. Mr. Scott’s precise profit is unknown, but his blind trust reported income of $120.5 million in 2017, compared with an average of $10.2 million in each of the previous three years. Although Mr. Scott is to play no role in managing investments in the trust, from 2013 to 2015 his son-in-law at the time sat as an observer on the company’s board, according to his résumé.

‘A Removable Blindfold’

Florida’s Constitution prohibits “conflict between public duty and private interests” and requires that statewide elected officials and candidates “file full and public disclosure of their financial interests.” The state’s ethics code bars those officials from owning shares in entities that are regulated by or do business with the state.

In 2011, Mr. Scott’s lawyers wrote to the Florida Commission on Ethics that Mr. Scott would transfer all his investments to a newly created blind trust. He intended to comply with state ethics laws, the lawyers wrote, “even if they require him to divest or restructure his holdings, with attendant economic detriment.”

But the governor’s disclosures show that he did not transfer all his assets to the blind trust, instead granting many to his wife. He also did not order that his assets be divested and the proceeds reinvested without his knowledge, which is the only way for a blind trust to truly circumvent conflicts of interest. There was no apparent economic detriment: The trust’s value nearly tripled to $215 million between 2011 and 2017.

Among other benefits, placing assets in a blind trust effectively allowed shareholding, which otherwise might have been prohibited, in companies with substantial state interests. That included Mr. Scott’s investment in NextEra Energy Partners, an arm of the company that owns the state’s largest utility, Florida Power & Light. The electricity provider is also a major Scott campaign donor.

Peter Antonacci, who was then the governor’s counsel and is now Florida’s commerce secretary, declined to comment for this article, and two private lawyers who worked on Mr. Scott’s blind trust, Richard E. Coates and James T. Fuller, did not respond to emails.

Laws and regulations governing blind trusts vary greatly by state, and 29 states do not address them at all, according to Nicholas Birdsong, a researcher with the National Conference of State Legislatures.

The blind trust that Mr. Scott established differs in important ways from those authorized under federal law and Senate rules. The federal system would, for instance, require annual disclosure of his wife’s assets; prohibit his former business associate, Alan L. Bazaar, from serving as trustee; and require regular disclosure of assets initially placed in the trust that have not been disposed of.

The New York Times’s examination found significant redundancy between the assets in Mr. Scott’s blind trust and those held by Mrs. Scott, even seven years after the trust’s formation. The July Senate disclosure showed that 91 percent of the 89 equity investments in the blind trust — those arguably most susceptible to conflict — were held in Mrs. Scott’s trusts and accounts as well. There also was commonality in their holdings of dozens of state and municipal bonds. (Mrs. Scott has assumed her husband’s campaign schedule while he directs the state’s recovery from Hurricane Michael.)

Chris Hartline, a campaign spokesman for Mr. Scott, said the governor had had no communication whatsoever about investments with either his wife or Mr. Bazaar, the manager of his blind trust. Mr. Bazaar, the chief executive of Hollow Brook Wealth Management in New York, was for years the managing director of Richard L. Scott Investments, the governor’s former firm. State records show he has also managed some of Mrs. Scott’s investments during her husband’s tenure as governor. He did not respond to a request for an interview.

In 2013, Florida’s Republican-controlled legislature unanimously passed a bill that made the mere existence of a blind trust an absolute defense against charges of conflicts of interest. The law set standards for blind trusts that simply mimicked the structure of Mr. Scott’s. A person closely involved with the drafting said the governor’s office was “heavily involved.”

“The Florida statute is more like a removable blindfold than a blind trust law,” said Dan Krassner, the former director of Integrity Florida, a government watchdog group. “You have the governor and first lady with similar investments and the first lady has full knowledge of them, and we’re supposed to believe that the governor’s not aware of his assets. It just doesn’t pass the smell test.”

Nonetheless, four months after Mr. Scott signed the blind trust bill, the state ethics commission, controlled by Republicans appointed by the governor and legislative leaders, ruled that his trust complied with the new law.

Florida’s law does not require officials to reveal the contents of blind trusts when running for re-election. Mr. Scott’s lawyers had told the ethics commission in 2013 that doing so “would be contrary to the purposes” of the trust and the new law.

But after Mr. Scott announced his 2014 campaign, they did precisely that by “unblinding” his trust, disclosing the contents and then returning them to a new blind trust. His lawyers said he had acted “in the interest of full and complete public transparency in the candidate qualifying process.” Three years after he created the blind trust, Mr. Scott again had full vision of his assets.