The U.S. footprint of interventions

For nearly two centuries, the United States has treated intervention as an instrument of routine policy, not an exceptional response to danger.

When historians count U.S. interventions abroad, the first difficulty is deciding what qualifies. Should it be only large-scale invasions and occupations? Or every instance of Marines landing, bombers flying, or special forces operating on foreign soil? Using the broad standard—all military interventions outside U.S. borders—the record is staggering and growing.

Now there’s a new impetus against the bogeyman du jour: Nicolás Maduro. In August 2025 it was reported that Trump had signed a directive in 2020 authorizing military action against drug cartels. The U.S. increased its naval presence in the Caribbean Sea under that “legal” cover, though the deployment was seen by many as a move to intimidate the Maduro regime and Trump has now openly admitted that what he seeks is regime change. He thinks an offer of $50 million to whoever provides information leading to the capture of Maduro will prove an irresistible temptation to an insider in the Venezuelan military. Or at least thinks that such an offer is an effective prop in his self-aggrandizing theater––the John Wayne cowboy that actually does something against the bad guy. Or both.

What is not right, not legal, not moral, not justified, is to be killing people by the handfuls who may be the worst drug runners in the world, but are still human beings with internationally recognized human rights that include due process. Even if convicted of importing tons of drugs into the U.S., accused drug runners would not be subject to summary execution, not to mention the denial of the right to confront their accusers, offer evidence in their defense, and require that the prosecution at least identify who the accused are and what they have done to deserve whatever punishment. Remember something quaint called habeas corpus?

As to Venezuela specifically, the White House justifies the actions not on the basis of the 2020 directive but under another secret directive from this year addressing “imminent threats.” According to the Pentagon, U.S. military strikes on small boats off the coast of Venezuela have killed dozens of people as of this writing. The U.S. claims the boats are carrying drugs and members of the Venezuelan gang Tren de Aragua but has offered no evidence of its claims. People in small boats who are running away from U.S. destroyers pose no danger whatsoever. Still, Trump has authorized covert CIA operations inside Venezuela, threatened possible ground intervention, and considered “taking out” Maduro. Trump has resorted to declaring that the U.S. is in a “non-international armed conflict” with certain Latin American drug cartels and accuses Maduro and other Venezuelan officials of participating in drug trafficking, again without offering evidence. The characterization of the conflict with the drug cartels frames these groups as “unlawful combatants,” which permits use of force under the laws of armed conflict in certain cases.

Several experts in international and domestic law, however, have challenged the Trump administration’s assertion that it has legal authority to treat suspected drug traffickers as wartime enemies rather than criminal defendants. They note that Congress has never authorized such an armed conflict under U.S. law.

Under international law, a nonstate actor can only be considered a legitimate party to an armed conflict—and thus subject to targeting based on membership rather than individual conduct—if it functions as an “organized armed group” with a unified command structure and participates in sustained military hostilities, a far cry from the situation here.

Trump has been busy with many other new or expanded military actions. In 2017 and 2018 U.S. forces conducted two direct missile strikes against the Syrian government in response to chemical weapons attacks blamed on the Assad regime. In January 2020, a U.S. drone strike killed Iranian Major General Qasem Soleimani at the Baghdad International Airport. This action significantly heightened tensions between the U.S. and Iran. The U.S. military under Trump also increased its counter-terrorism operations, particularly drone strikes, against al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP).

The Trump administration wasted no time in his second term in conducting airstrikes and drone attacks in Somalia targeting ISIS affiliates. In June 2025, Trump claimed to have ordered Tomahawk cruise missile strikes on three Iranian nuclear sites also bombed by Israel, which intensified U.S.–Iran tensions and drew sharp international criticism. Early in his first term, he also ordered a U.S.–UAE raid against an al-Qaeda stronghold in Yemen (Yakla, al-Bayda Province). U.S. forces sustained casualties; civilians reportedly died. His administration also escalated air campaigns and provided support to the Saudi-led coalition in Yemen. Not least, Trump ordered a major air and naval campaign (March–May 2025) against Houthi forces in Yemen, hitting radar systems, launch sites, air defenses, and more. The strikes led to hundreds of Houthi casualties and allegations of civilian harm.

Now Trump struts in the Middle East taking credit for ending another war (is it the eighth?), like an arsonist returning to the scene of the crime as a fireman and boasting that he put out the blaze, considering he could have ended the Gaza conflict long ago simply by warning Netanyahu that the U.S. would stop funding the war.

This is a pattern in American history. The United States first projected power close to home and Mexico lost half its territory after the 1846–48 war. Marines landed repeatedly in Central America and the Caribbean in the early 20th century: Haiti (1915–34), the Dominican Republic (1916–24), Nicaragua (1912–33), and Panama (multiple interventions culminating in the 1989 invasion). Cuba was invaded in 1898, occupied several times afterward, and saw the failed Bay of Pigs landing in 1961. By the 1930s, the U.S. military had intervened more than 30 times in Latin America and the Caribbean alone.

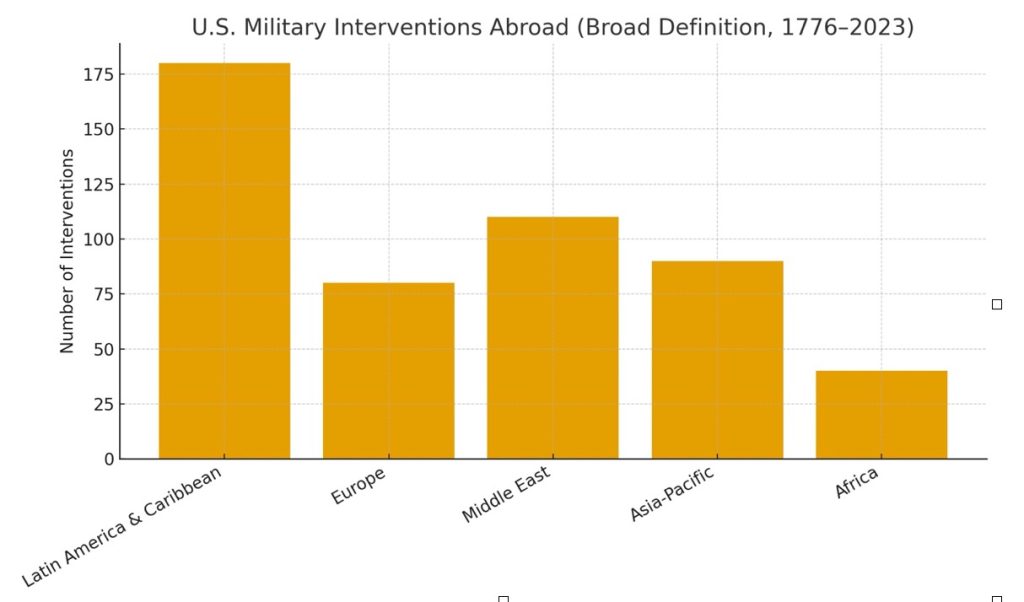

The chart below shows approximate counts of U.S. military interventions by world region:

North America and the Caribbean dominate the early record, reflecting geographic proximity and strategic interests. Asia-Pacific and the Middle East rise in prominence in the 20th and 21st centuries, while Europe and Africa show fewer but still consequential interventions.

North America and the Caribbean dominate the early record, reflecting geographic proximity and strategic interests. Asia-Pacific and the Middle East rise in prominence in the 20th and 21st centuries, while Europe and Africa show fewer but still consequential interventions.

The pattern is unmistakable and Trump has continued it despite his preposterous quest for the Nobel Peace Prize. For nearly two centuries, the United States has treated intervention as an instrument of routine policy, not an exceptional response to danger. The rhetoric—freedom, security, democracy—changes with the era, but the practice endures: coercion abroad enabled by falsehoods and indifference at home. Today’s aggression, present and planned, against Venezuela differs from the occupations of Nicaragua or the bombing of Hanoi and Baghdad only in technology and pretext. The deeper continuity is moral—the conviction that American force carries its own legitimacy and that American lives are more valuable than others by a long shot. Until that illusion is confronted, the map of U.S. power will remain a record not of defense, but of hegemony.