The city of ‘Cubaneo’

MIAMI — “Don’t go to Miami. It’s full of Cubans,” my friend was told by his bosom buddy days before taking the plane that flew him from Cuba to Mexico, so he could cross the border into the U.S.

The bosom buddy is a fellow “with brains,” who has been living outside Cuba for 12 years. So my friend trusted blindly in his emphasis to distance himself from the world’s largest community of Cuban émigrés.

My friend thought only briefly about the advice before choosing between the addresses that he could put down as destinations in the U.S. on his application for political asylum.

In his right pocket my friend carried a letter from a relative in California who promised him work in his prosperous business as soon as he arrived in the U.S.

In his left pocket he carried the coordinates for his elderly aunt, with whom he had lived much of his childhood. She offered him the sofa in her East Hialeah apartment, paid for with the help of Government-funded Section Eight housing.

As soon as he left San Diego Airport, he realized that everything would be different from what he expected. The support from his relative — a naturalized U.S. citizen since the age of 7 — lasted only a few days. The Central American construction workers who worked with my friend were noble people but inexperienced in guiding him through the paperwork required by his status.

Two months later, tired of eating tacos, frustrated because no one understood his jokes, and tired of shuttling between state offices to request the assistance provided by a Cuban Adjustment Act that few people had ever heard of, he stuffed his clothes into a backpack and bought an air ticket to Miami, where he was welcomed with beer, tamales and barbecued pork by neighborhood friends he last saw in 1994.

My friend chose to leave Cuba mainly because his salary as a professional was not enough to give his children a better life, because he wanted to exploit his talent to the max and see the world. He also wanted to flee the suffocating heat, the contemptuous treatment by receptionists, the bureaucracy, the political interpretations, the loud musical groups drowning out his conversations, the vulgarity.

He wanted to leave an environment that didn’t lead anywhere, so he was reluctant to go to Miami where, he had been told, “Cubaneo” is widespread.

That word, which still has not been added to the Royal Academy’s Dictionary of the Spanish Language, has been the subject of reflections by intellectuals such as Fernando Ortiz, Juan Marinello and Jorge Mañach. In the flavorful sauce of our national identity, Cubaneo translates into the attitude, temperament, character and performance of everything Cuban.

There is Cubaneo on the island but also anywhere where natives of Cuba gather. Popularly, it is associated with the stridency typical of our idiosyncrasy, the humorous reactions to any problem, the excessive gesturing, the shameless audacity, the meddlesomeness, and the tendency to “resolve.”

The “quítate mijo,” the “oye tú,” and the “asere,” the dance in the middle of the street; the lack of privacy in family surroundings; the need to correct an argument overheard from strangers before crossing the street.

In South Florida, home to most of the 2 million émigrés from the Caribbean island, this mode of relating to one another became widespread. It is no secret that, beginning half a century ago, the Cubans stole the soul from the American city closest to their island and redesigned Miami by dint of their nostalgia.

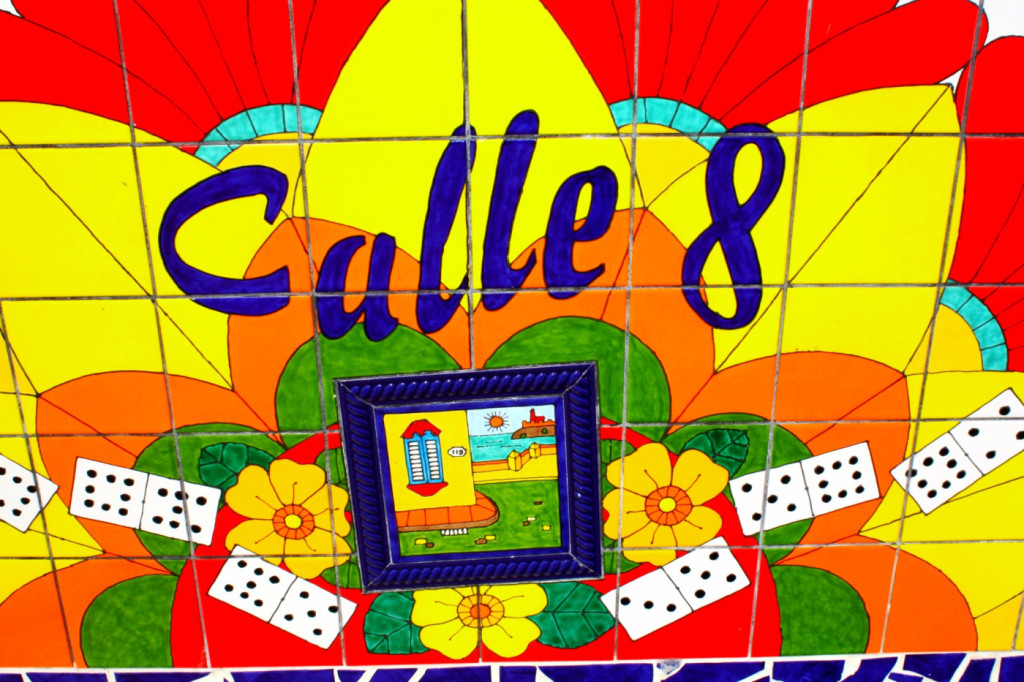

On any street corner in Miami you can find Conchita guava bars, Hatuey malt beer, peanut nougat, tamales (wrapped or stewed), ham sandwiches, tamarind juice. On Calle Ocho [Southwest 8th Street] you’ll find books, watches and paperweights dating to the period of the Cuban Republic, you’ll be served mojitos and you can watch domino tournaments played by men who loudly discuss the effects of a double-blank opening.

Miami Cubans almost always talk about politics and there’s a tendency to prejudge people because of their ideology, same as happens in Havana. Of course, you will find the tricksters who manipulate the system to “live from creativity” rather than work for a living, the Cubans who speak loudly in public places, those who blow the horn at intersections, and those who ignore the main rule of marketing if a client gives them a hard time.

Cubans who replicate the northern culture believe that all that is a display of stubbornness. Why insist on retaining customs that come from an underdeveloped country, they ask. Far better, they say, to move north from Florida, to move where the real American way of life can be found, where the minimum wage is higher and the house rentals are lower.

Cubans do live in New Jersey, Boston, Pennsylvania, Tampa and Minnesota, of course. Cubans also live in Egypt, Mexico, Turkey, Ecuador, Dubai and Germany. However, to begin a life abroad, arriving in Miami continues to be an advantage.

That’s not only because of the bilingual offices that swiftly issue the benefits that the U.S. government grants to newly arrived Cubans, or because of the tropical climate or the in-your-face attitude.

What makes this city special among the island’s émigrés comes from Cubaneo. It is the support network painstakingly woven by the more than 1 million Cubans living in Miami.

Just to listen to an accent similar to one’s own is a guarantee of encouragement. Implicit in Cubaneo is the solidarity of those who, if they can, will “throw you a rope.” (Roughly translated, ‘will help you out.’)

One of the youths with whom my friend used to play baseball in La Lisa* got him his first job. Others bought him clothing, invited him to their homes on weekends, took him to the beach and, every so often, phoned to asked how he was doing.

After a year, he feels ready to try his luck in another state. Miami gave him the breathing space he needed not to break down.

In the Sun City, Cubaneo has shadings. Among others, I choose the conspiratorial whisper from a cashier who corrects my purchase so that it will be cheaper. Miami Cubans are far from being a uniform and perfect whole, but it is nice to find among them some unselfish folks who are ready to keep a countryman out of trouble.

*A neighborhood in Havana.