The blockade/embargo on Cuba explained

The US's concern is to promote democratic progress. Currently, the US government's representatives are among the least likely to offer lessons in democracy.

There’s an Aesop fable we used to hear as children, in which a shepherd always cried wolf, and when the wolf really came, no one helped him because they no longer believed him.

A similar thing is happening with the Cuban government. It has flooded the official discourse with references to the blockade without accepting responsibility, so many people no longer believe it.

It’s hard to find an objective analysis of US policy toward Cuba and its role in the nation’s crisis. The Cuban authorities haven’t been able to present a convincing explanation of its impacts, but that doesn’t make it any less true.

As long as the Cuban government doesn’t fulfill its duty of explaining to citizens how the sanctions work, civil society will have to do it. So please bear with me.

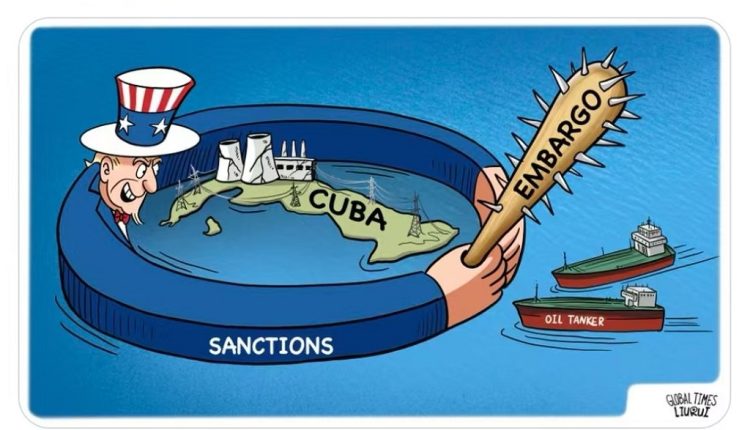

The Cuban government regards it as a blockade because it sees it as an economic and political siege; for the opposition, it’s an embargo because that’s the legal definition in the US, and they see it as just a trade restriction. The blockade suggests a complete siege, while the embargo narrows the focus of the economic and political conflict against Cuba. The United Nations refers to these as unilateral coercive measures because they haven’t been approved by the UN Security Council, which is the only entity with the legal authority under international law to impose collective sanctions. Imposing sanctions outside a country’s territory is considered illegal because it violates sovereignty and non-interference principles.

We know that the news or Cubadebate will remind you of some of these things. And some will say we’re messing with the chain, not the monkey. However, at La Joven Cuba, we won’t downplay anything to avoid comparisons. If tomorrow the Cuban government claims the Earth is spherical, we’re not going to say it’s flat just to disagree.

Among Cubans, there are strong and conflicting opinions on these measures, but the international community remains very clear. Each year, most countries with left-wing, right-wing, or centrist governments vote against them.

So, if you believe that unilateral measures don’t exist, even if all your Facebook friends agree with you, I’m sorry to tell you that you’re in the minority.

The United States’ policy toward Cuba is increasingly hostile. However, American experts agree that the relationship should be based on pragmatic engagement, meaning practical interaction. From that viewpoint, a responsible policy toward Cuba would start with removing it from the list of state sponsors of terrorism and ending unilateral measures.

But we recognize that developing a rational policy toward Cuba is challenging. However, since the Chargé d’Affaires has expressed considerable concern, here are four steps he could propose to the State Department. If Marco Rubio can make concessions with Russia, which is currently invading Ukraine, he should have no trouble making these minor adjustments toward a country that isn’t engaged in invasion.

Internet

The U.S. Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) permits, through a general license, the installation of telecommunications infrastructure like fiber optic cables or satellite links to offer services between the United States, third countries, and Cuba. So far, so good.

Now, to make this license effective, additional permits from US regulatory agencies like the Federal Communications Commission are required, along with national security reviews by the so-called Team Telecom. Due to all the red tape, companies that could provide these services fear sanctions, know they won’t easily get financing for these projects, and ultimately consider the shifting attitude in Washington because, with respect to Cuba, what is allowed today might be forbidden tomorrow. Therefore, the company prefers to be cautious rather than risk a lawsuit.

Blackouts

The US Export Administration Regulation requires that the Bureau of Industry and Security license essential components and technology for repairing and maintaining the electrical system before it is shipped to Cuba. Exceptions apply only in some cases, but there is no general authorization that covers all electrical equipment.

Furthermore, OFAC permits payments and contracts only if the exports have been previously approved by the Bureau. There is also a general license from OFACl for services related to repairing and improving infrastructure that directly benefits the population. However, in practice, the same issues arise: excessive paperwork, companies’ fear of sanctions, and banking restrictions that ultimately delay or block these operations entirely.

Food

Today, most Cubans believe that Cuba imports a significant amount of chicken from the United States, mainly due to price and availability. The US legal framework permits the export of agricultural products under an exception called AGR, established in the US Export Administration Regulations, but it requires prior notification to the Bureau of Industry and Security and adherence to specific conditions.

OFAC authorizes payments and contracts only if the exports have already been approved by the Bureau. The Trade Sanction Reform and Export Enhancement Act states that these payments must be made in advance, in cash, or through third-country banks, but never with financing from U.S. banks.

All of this means that the variety of food Cuba can import from the United States is limited. Although the government also imports chicken, there is a significant amount because private Cuban businesses find ways to meet these requirements or work around them. This is partly due to US farmers lobbying for these exceptions. In short, the paperwork maze affects not only the government but also private companies. If it were a little easier, perhaps more food would be imported into Cuba by more Cuban-owned businesses.

However, Congresswoman María Elvira Salazar is doing everything she can to ensure that private individuals can’t do this either.

Health

Although it is theoretically allowed to export medicines and medical devices to Cuba, in practice shipments are blocked by legal and operational hurdles. They require a license from the Bureau of Industry and Security, and the Office of Asset Control grants payments if those transactions have already been approved by the Bureau.

However, there is an elephant in the room: the Cuban Democracy Act requires the president of the United States to verify on Cuban territory the intended use of medicines or medical equipment, unless they are donations to NGOs. This verification must be documented through a memorandum or official certification in the Federal Register. Without this presidential determination, neither the Bureau nor OFAC can approve the licenses.

Furthermore, the Trade Sanction Reform and Export Enhancement Act requires that each license to export medicines be valid for one year, so once it expires, you will have to start all over again.

***

Common export regulations in any country, which of course involve a lot of paperwork, are normal and necessary, but requiring presidential approval in a bureaucratic process… that’s not normal. It’s one of the many crazy things happening in Cuba.

The United States’ concern is supposedly to promote democratic progress in Cuba. Perhaps the previous administration could have made some democratic demands, but not the current one, which is building a private militia for the White House with masked federal agents kidnapping people in the streets, and a president facing public evidence of corruption. Currently, the US government’s representatives are among the least likely to offer lessons in democracy.

This hostile policy toward Cuba only acts as another incentive to freeze the island in time. If anything has been proven in practice, it is that democratic progress comes through rapprochement.

Mariana: Surely US diplomats would prefer the high-level diplomacy practiced by Ben Rhodes and Jeffrey DeLaurentis during normalization. And Cubans would surely prefer the embassy that granted visas, and the diplomacy that brought the Rolling Stones to the Ciudad Deportiva, the Tampa Bay Rays to the Estadio Latinoamericano, and tourists to Old Havana. Instead, what we have now is a diplomat who offers only handshakes.

Like Aesop’s fable, many Cubans no longer want to hear about unilateral measures, even though they cause empty plates, blackouts in homes, and pharmacies to run out of medicine. Nor can we ignore the fact that the crisis is worsened by a flawed domestic economic policy and an exclusionary political system. Added to this is a public communication system that fails to meet its social commitment to the citizens. However, none of the criticisms we can direct at the Cuban government today justifies a policy of external aggression.

No political change is worth the misery of a country; no handshake can make up for the impact of the measures on the people, and no democracy can arise from poverty.