A story about hurricanes II

I have to meet this man, Bob Dylan said to himself, and closed the book. On the cover, in gold letters: “The Sixteenth Round: From Number 1 Contender to Number 45472.”

Under the title, the image of a man with a thick beard, shaven head and small, almost invisible eyeglasses, who looked at the camera from behind prison bars.

His eyes — strabismic eyes that didn’t seem to focus in the same spot — revealed an ambiguous mix of anger, desperation and boredom. The book was the autobiography that Rubin “Hurricane” Carter had written in prison during the first eight years of his life sentence.

They say that Dylan went to New Jersey to visit the prison where Carter resided, a few weeks after he read the book. But this could be as unreal as Dylan himself, of whom little is known. From that first encounter, if it happened, there is little record.

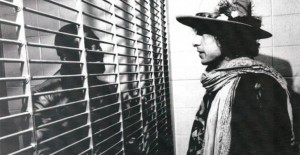

However, several photographs have survived from another visit Dylan made months later to the Clinton prison. In one of them, Dylan is seen wearing a scarf, long hair and a flowered hat, an absolute anachronism with the place. He stands before a barred cell door, behind which is Rubin, small eyeglasses and leather jacket, in a gesture that implies conversation.

The image’s contrast is almost aggressive, not only because the two men do not resemble at all but also because both represent worlds that are totally opposite.

One was a musician, a poet, an artist, someone who looked at life from the edge, finding angles, corners that others barely could sense; a man who changed his skin at will, out of either boredom or habit; someone who played at tossing songs into the wind that not even he fully understood.

The other had spent more than half his life in prison, and during the brief vacations in which he was outside, alone, had done only one of two things: to steal or punch.

Yes, contrary to what John Donne thought, in the end, each man is an island and these two men were in the antipodes. Nevertheless, after spending hours talking with Carter, shortly after his first visit, Dylan is supposed to have said, “I noticed that that man’s philosophy and man ran along the same road, and one doesn’t usually know many persons of that type.”

It is very likely that by then Dylan already sensed that Rubin Carter, the Hurricane, would become a song.

Certainly it wasn’t the first time that he composed a song of that type, of those that the critics call an accusatory or protest song. There was some of that in “Blowin’ in the Wind” and also in “George Jackson” — dedicated to the leader of the Black Panthers who was murdered in prison– or in “The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll,” which recreates the death of a black waitress at the Emerson Hotel in Baltimore, beaten to death with a cane by a white young man.

Certainly it wasn’t the first time that he composed a song of that type, of those that the critics call an accusatory or protest song. There was some of that in “Blowin’ in the Wind” and also in “George Jackson” — dedicated to the leader of the Black Panthers who was murdered in prison– or in “The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll,” which recreates the death of a black waitress at the Emerson Hotel in Baltimore, beaten to death with a cane by a white young man.

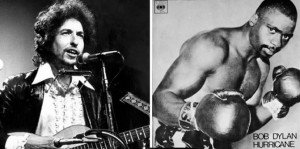

To write “Hurricane,” Dylan closeted himself in a room with theater director Jacques Levy, with whom he had written almost all the songs in the album “Desire.” In a short while, they recorded the first version.

The Columbia Records lawyers, always attentive to detail, suggested that Dylan change a couple of verses to avoid possible lawsuits. Dylan agree and not only changed the words but also recorded a much faster version that lasted more than eight minutes.

“Hurricane” tells, with an agile and continuous rhythm in the style of a road movie, what happened on the morning of June 17, 1966, when three persons were murdered at the Lafayette Bar in Paterson, N.J.

Listening to it, one can almost hear the shots, see the blood, feel the shock felt by Alfred Bello, a common thief, and Patty Valentine, the upstairs neighbor, when they found the bodies; the pressure exerted by the police to inculpate Carter and John Artis, an acquaintance with whom Rubin was riding that night in his Dodge Polara, near the scene of the crime; the hostility of a jury composed exclusively of whites; the brutal weight of the sentence (one life term for each murder); the infinite solitude of Rubin, who might someday have become world middleweight champion, meditating like Buddha in his cell.

Bob Dylan included “Hurricane” in each of the concerts of the Rolling Thunder Revue, his 1975 tour, and the song soon became a hit, as the hymn for Rubin Carter’s cause. Some say that, partly because of the song and its impact, Carter and Artis were given a second trial and nine months of freedom on parole.

But the life sentences were reinstated on Dec. 22, 1976. It wasn’t until late 1985 that Judge Haddon Lee Sarokin threw out the charges against Carter and Artis, saying that the men had been sentenced in a climate of racism.

Even today, some insist that Rubin was guilty and that he was released through a technicality. Such is the case of Cal Deal, a journalist who covered the trials in New Jersey and now lives in Florida. He took the trouble to create a website where he belies Dylan’s song, verse by verse.

The thousands of people who still listen to “Hurricane” are not aware of this.

Rubin Carter never boxed again; his time was over. He went to live in a commune in Canada and later founded the Association in Defense of the Wrongly Convicted. He died last April, fighting a prostate cancer that had him on the ropes. In a corner, next to his bed, was John Artis.

Shortly before dying, Rubin wrote: “If I find a heaven after this life, I’ll be quite surprised. In my own years on this planet, though, I lived in hell for the first 49 years, and have been in heaven for the past 28 years. To live in a world where truth matters and justice, however late, really happens, that world would be heaven enough for us all.”

As to Bob Dylan, they say that he continued to make records, painting pictures and writing poems. He won several Grammys and there was even talk of a Nobel prize for literature, but he never again sang “Hurricane” in public. Some say that they saw him in a Chrysler commercial in the latest Super Bowl, but that’s very unlikely.

Did a man who could write all those songs and live that many lives really exist? Could he be a myth? Have I been writing fables these past two weeks? The answer, my friend, is blowin’ in the wind, the same wind that keeps bringing back the songs that never die.