The guest at the Carlyle

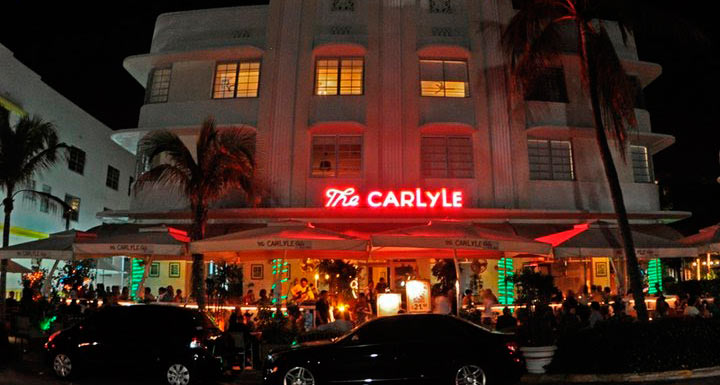

MIAMI.- The Carlyle hotel — not the imposing edifice on New York’s Madison Avenue but a much smaller and modest country cousin on a small corner of Miami Beach — still retains some of the old glamour that is usually associated with the 1950s.

A glamour that really began a couple of decades earlier, during that common fever that afflicted so many architects, known as Art Deco.

Designed by the German architect Richard Kiehnel, the hotel was built in 1939. Miami Beach’s Art Deco district blossomed as investors from the North tried to palliate the Depression by building rows of small hotels along Collins Avenue and Ocean Drive.

Oddly enough, a few years later, the United States entered the Second World War and almost all the hotels filled with recruits, instead of tourists.

Today, 75 years later, the Carlyle displays the same vertical lines on its facade, the same curved angles, the same decorations and pastel tones that it had at its inauguration.

Several scenes of “Scarface” were filmed there. Tony Montana’s awful Cuban accent (perhaps Al Pacino’s most mediocre role), the sounds of electric saws and bullets also became part of the hotel’s décor. This week, however, the Carlyle’s name is associated with a different movie, a comedy of errors that premiered in 1996 — “The Birdcage.”

The movie was filmed at the hotel and was based on the 1978 French movie “La Cage Aux Folles.” In it, the principal actor — a hairy-chested fellow — played a gay man who must pass for straight in order to cause a good impression on his son’s in-laws, an ultraconservative Republican couple from Ohio.

During his cinema career, that actor also played an extraterrestrial, a boy in the body of a man, a man disguised as a woman, a professor of literature, a robot with a soul, Andy Kaufman’s grandmother, a genie from a lamp, a hologram, a psychopathic writer, Peter Pan, President Theodore Roosevelt and himself — perhaps the most difficult of all his characters.

Those who knew him say that, although he was one of brightest comedians who ever lived, he was in reality an extremely melancholy man.

They say that, in the times when he wasn’t singing, dancing or improvising some clever statement, during those moments when he waited to go onstage to deliver a monologue, when he was not inside the skin of a character, he was a timid and withdrawn fellow who sat in a corner to stare blankly into space and battle his demons.

In almost all photographs, he smiles as if trying to hide something, but deep inside his eyes one can perceive a grimace of pain.

Much has been said lately about that topic: comedians who are funny because they have no choice, because it’s their only way to deal with depression. Common terms have been created, such as bipolar disturbance, suicidal instinct, psychosis, and the old metaphor, repeated in infinite variations, “the sad clown.”

But I don’t think that anyone has come even close to understand what went through this man’s head on the last night of his life.

Last Monday, he was found dead at his home in California. At first glance, he appeared to be sitting but, if one looked carefully, one could see that he was hanging from his neck with a belt secured between a closet door and the door frame.

Before dying, he had cut himself on the wrists with a pocket knife. On the death certificate, on the blank describing the cause of death, the coroner wrote “asphyxia.”

Today, in a window next to the main entrance to the Carlyle, we can see a picture of him, with the same moustache he wore for the movie and his eyes open wide, those eyes that — beyond the thousand faces — never could lie.

People walking down Ocean Drive toward the beach see the photograph and shake their heads: “Poor guy, he spent his life making others laugh and died of sadness.”