A story about hurricanes (I)

Actually, this is the story of a song. Hurricanes and men go by; songs, those that are worthwhile, are a lot more tangible, solid, lasting.

The song I refer to begins with pistol shots in the middle of the night, a bar room and a pool of blood, the sound of a guitar, a harmonica, a violin, drums and a ragged voice. No more is needed. The rest, everything that involves the essence of the song, its authors and characters have already died, or very possibly never existed.

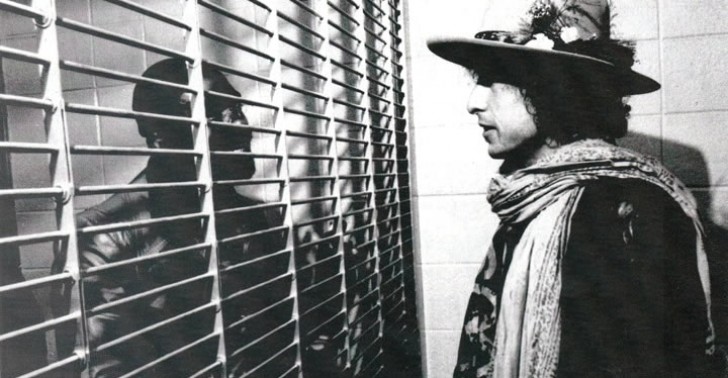

Such is the case of Bob Dylan, someone who nobody has gotten to truly know. Some say that he was a musician, others that he was a poet, others that he was a cartoonist, an actor, a preacher, a professional vagabond, a collector of old songs, a professional young man, a somnambulist awake, an agitator at the barricades, a surrealist philosopher, or a thief of vinyl records.

Others will say that he was all of that at once. Others will even insist that he never existed, that he was a fictional character whom people usually mistake for one Robert Allen Zimmerman, a Jewish boy from Hibbing, Minn., descendent of Ukrainians on the father’s side and Lithuanians on the mother’s side.

A plain, ordinary kid with his hair combed properly, an angelic look and a picture in his school’s yearbook. Nothing to do with the mythical Bob Dylan.

The other character in this story — its protagonist, if you will — lived a life much closer to reality, easier to track down because he was in prison and nothing hardens men more than direct contact with death, as happens in wars, hospitals and prisons. Apparently, Rubin Carter spent a lot of time in the latter.

He was born in Clifton, N.J., in 1937, the fourth son in a family of seven siblings. His father worked in a rubber factory and delivered ice in the mornings. It was he who turned the 9-year-old Rubin to the police for the first time, after learning that his son and other boys had stolen clothing from a store.

Two years later, Rubin was sent to a reform school in Jamesburg, N.J., after stabbing a man. Some say he did it in self-defense, others that it was during a robbery. The thing is that he spent six years in a place where criminals were not reformed but stored.

In 1954 he escaped, enlisted in the Army and was sent to West Germany. There, he took up boxing. Later, in 1956, he returned to New Jersey and was sent to prison for having escaped from reform school.

Carter had not yet served his sentence when Bob Dylan — if he indeed existed — enrolled in the University of Minnesota. Although he didn’t spend much time there, he never went to class and spent the nights playing his guitar and listening to borrowed phonograph records that he never returned.

Shortly thereafter, he went to New York City to meet Woody Guthrie, the old melancholy troubadour who was spending his final days in a psychiatric hospital.

They say that Tommy Johnson sold his soul to the Devil, just so he could turn him into the world’s best blues guitarist. Dylan did the same with Guthrie, who gave him a couple of songs, a harness that enabled him to play the harmonica without using his hands, and the best tricks that he kept in his fascist-killing machine, i.e., his guitar.

That same year, 1961, Bob Dylan signed a contract with Columbia Records and months later recorded his first disc.

Also in that year, Rubin Carter became a professional boxer. On Sept. 22, 1961, just one day after leaving prison, he fought his first fight and won. On the ring, everything was much simpler; he knew who his opponent was and what to do with him — knock him down and, if possible, avoid being punched too much. Rubin learned that the faster he accomplished that, the better.

So he became famous for his lightning knockouts, with a powerful left hook that made up for his short stature, lower than the average height for a middleweight. He wasn’t considered a stylist. His style, if one existed, was rather disorderly, a rain of blows that came from everywhere. The best an opponent could do was to take cover, so Carter earned the nickname “Hurricane” — Rubin “Hurricane” Carter.

Of the 27 victories in his short professional career — barely five years — 19 were by knockout. The quickest one was probably the one he inflicted on Florentino “The Ox” Fernández, who was born in Santiago de Cuba in 1936 and died in Miami last year. Fernández lasted only a few seconds on the ring before he collapsed like a tired ox.

Another famous fight was the one he won, in a first-round technical knockout, against Emile Griffith, the world welterweight champion. It shocked the world of boxing. But another Cuban, Luis Manuel “Ugly” Rodríguez, beat him twice, in February and August 1965. Both fights ended in the 10th round.

One year earlier, Carter had fought Joey Giardello for the middleweight title. An exhausting fight, 15 rounds, that Rubin lost by a scant margin.

On the morning of June 17, 1966, a few months after the first and only tie in his career — against Wilbert McClure — Rubin Carter was arrested while driving his Dodge Polara. That was apparently one more arrest among the many in his life. Three while persons had been murdered at the Lafayette Bar in Paterson, N.J. Rubin Carter was black.

By that time, Bob Dylan was sick of everything and needed a break. He had recorded seven albums, participated in the civil rights movement, sung with Joan Baez, taken part in the March on Washington on Aug. 28, 1963, joined the protest-song movement, toured the U.S., Canada and Europe.

He had put aside his acoustic guitar and his image of timid young man, in the Woody Guthrie manner, to embrace the electric and aggressive sound of rock ‘n’ roll. He had lied to the press about his past, had been loved and hated, had spat on everyone’s face and drank to excess. While doing all that, he had written “Blowin’ in the Wind” and “Like a Rolling Stone.”

The aforesaid is, no doubt, an exaggeration by his biographers or maybe by Dylan himself — if he ever existed. Nobody could have done so much in such a short time. The only thing we can affirm with some certainty is that it is very unlikely that Dylan at that time heard about the murders or about Rubin Carter, a boxer without much relevance.

And he probably didn’t imagine or even intuit the song he would write nine years later, which is, after all, what this story is all about.

(Next Friday we shall publish the second and final part of this story about hurricanes.)