Self-employment and other forms of employment

The long-standing discussion about the role of private and cooperative employment in Cuba has finally reached a new level. What should the objective be? Recently, authorities have offered nuanced clues. Ideas range from self-employment as a “form of employment” in sensitive segments such as the food sector, to alternatives in order to increase exports.

First we must abandon the euphemisms. The current Constitution is clear regarding the recognition of private property over means of production. Confusion is not gratuitous, it has consequences for policies. ‘Self-employment’ includes activities of very diverse size, complexity, and prospects for expansion.

For example, the promotion of very simple segments whose objective is the creation of employment and survival requires instruments that are very different from those needed for what Latin America literature recognizes as “dynamic enterprises.” In Uruguay, the latter is clearly identified early in such a way that they have access to specific support. In other words, the ecosystem of institutions and policies that nurture a dynamic small business is very different in each case.

Various studies in the region reveal the perverse effects on productivity, which come from maintaining a fabric of many, very small companies that cannot grow. The proposal in this area is that the regulatory framework recognizes these differences, and stimulate the creation of institutions and support policies that accompany the entrepreneurial process in its different phases, according to its characteristics.

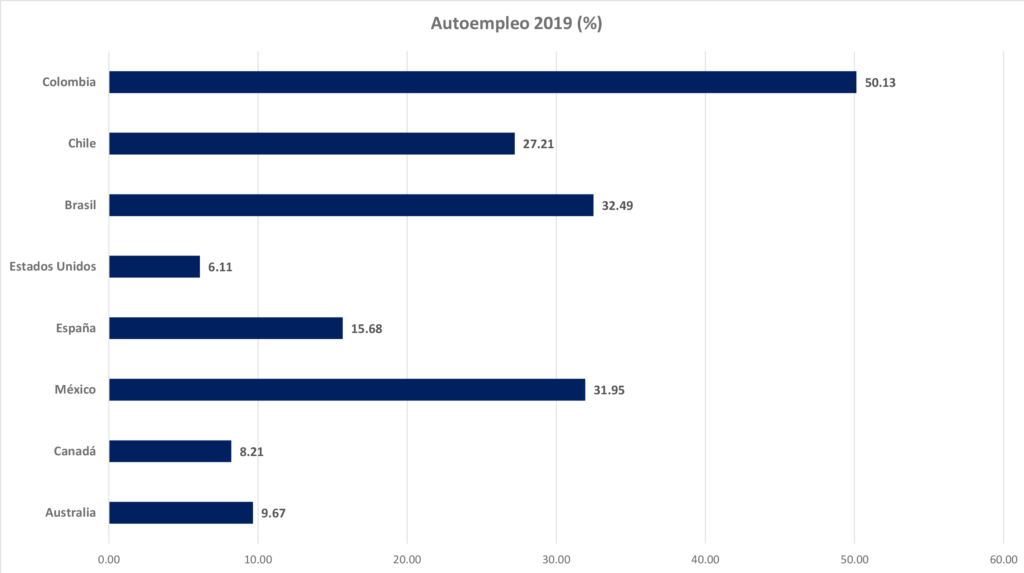

Making matters worse, the current framework mixes owners and employees, self-employment and small business. Self-employment fulfills productive and social functions in all countries, in different ways. In Colombia it is 50 percent of its total employment, while in Japan it is 10 percent. In some cases it exists as the only employment alternative, in others it has to do with personal undertakings. It would be interesting to know what part of Cuban “self-employment” is really that, self-employment, and what the figures would be if all the informal ‘companies’ are added to the mix. Almost the same conceptual confusion can be applied to cooperatives, be they agricultural or urban.

It is also well known that various cooperatives are closer to constituting parastatal entities in their functions and decision-making mechanisms. Both segments, private and cooperative, have suffered from a narrow, arbitrary and inflexible interpretation of their property rights, both in the legal and economic spheres. Corrections are necessary without denying the restrictions for reasons of social interest, because the resulting distortions have a harmful effect on economic and social results. The legal norms must use precise terms, adjusted to the national reality. This terminology is assumed, first of all, by official communication as the first step for its extension to the entire society.

Under the previous logic, the private and cooperative sector is called upon to play a role that goes far beyond being a simple “employment modality,” or a reservoir of redundant positions. The disproportions observed in the productive sphere are not minor. Labor productivity is very low, even without data that allow for reliable international comparisons. Furthermore, its levels are widely dispersed among the different activities. Under the assumption that export sectors have productivity comparable to their peers in the area, in 2018 approximately five percent of those employed in Cuba were responsible for 55 percent of total foreign sales. Likewise, the Island has one of the lowest figures for exports of goods per capita in Latin America, with 212 dollars a year (2018), which, even considering the U.S. sanctions, is inexplicable for a country of its size.

Even in the most optimistic situation, thinking that many small businesses will close that gap is unrealistic. With a less problematic route, SMEs (small and medium sized businesses) represent around five percent of the value of exports in Latin America, although in Chile it reaches 13 percent and in the European Union 33 percent (they are not the same SMEs). But even then, although the non-state sector will not be directly responsible for exports, it can contribute in various ways to increasing the competitiveness of companies that sell abroad and the economic fabric in general. Sometimes they provide accessory services that improve the competence (consulting, transportation, packaging, design), or the labor productivity (services to the home and people, transportation, for example).

The proposal is for the promotion and full participation of the sector in foreign trade, leaving aside collection as a primary objective in the short term. More importantly, linkages with all productive entities should be promoted, regardless of their type. If there are obstacles they should be in productivityThe private and cooperative sectors have suffered from a narrow, arbitrary and inflexible interpretation of their property rights, both legally and in the economic sphere., not institutional or administrative.

Another trend that has been consolidating is the increase in informality. Research reports a wide variety of reasons and characteristics. But the almost unanimous opinion is that it is a negative development, particularly in a country that offers significant social benefits. High rates of economic activity and an impossible broad base are conditions for the sustainability of a welfare state. The economic activity rate in Cuba has fallen steadily since 2009. In 2018, just 64 percent of the working-age population had a formal job. This is particularly paradoxical given that appreciable changes were introduced in self-employment and urban cooperatives during that period. Which clearly tells us that that approach was very restrictive, and did not respond to the needs of productive development. Furthermore, some research suggests that tax evasion and underreporting have to do with institutional determinants of the regulatory framework, and especially the perception that the tax burden is high. In the new context, the adaptation of the tax code and the incentives for formalization, in general, must form an organic part of the institutional framework.

Backwardness of the non-state sector is linked to the perception that it occupies the lowest scale in economic development based on the characteristics of the activities that are grouped in it. More than a characteristic, this has been an implicit policy objective. Even when considering that the private sector is not dominant, this should not be equated with the nature of its activities, or levels of productivity. One of the contradictions that has slowed the sector to date is its almost total divorce from the workforce’s educational profile. While there are one-fifth of professionals in the working population, complex activities have been basically excluded from self-employment, where a better return on investment in training can be obtained. Statements regarding the removal from the list of allowed categories have met with almost unanimous acceptance, and are a key step in that purpose. The scope of the business must be precisely determined by the socioeconomic conditions and the regulatory framework that safeguards certain necessary balances. This must become an explicit objective of public policy.

The private and cooperative sector is already decisive in agricultural production, but also in tourism. However, in both, one must take into account the damage that results from a restrictive and short-term vision. The State enterprise, sooner or later, will have to be restructured. Instead of seeing the non-state sector as a threat to its survival or to the stability of its workforce, it must be turned into a key ally to soften the consequences of that process, offering the necessary flexibility to the economy to maintain social cohesion. Depressed levels of investment and lack of support from the financial system continue to be a weak link. Modernization of banks and similar institutions, and their adaptation to new conditions, is decisive for success.

An efficient and productive transformation essentially must come by transferring the workforce to highly productivity dynamic sectors. Identifying these sectors is not possible with total certainty, and the evidence that the State is the only entity capable of doing so is not conclusive. Along the way some current activities will be replaced by new engines of growth. If that is the key challenge that Cuba faces, then a very different role must be found for the private sector and cooperatives.