Postwar philosophy

MIAMI — Maybe you don’t know it, but the World Cup is over. Little matters what happens on Sunday; little matters that Germany does what almost everyone expect from it and pummels this badly caulked Argentina. It would matter even less if Messi woke up and achieved the miracle of avenging the four goals in 2010.

Nor does it matter that the Ticos — who have just christened a stadium with the name Keylor Navas, their heroic goalie — eliminated two world champions and slipped into the quarter-finals. That the best player in the group phase was a 22-year-old Colombian who is not even a starter in AS Monaco. That the Chileans were closer than a shot on a goalpost to beat the Germans. That Luisito Rodríguez sank his teeth on someone once again.

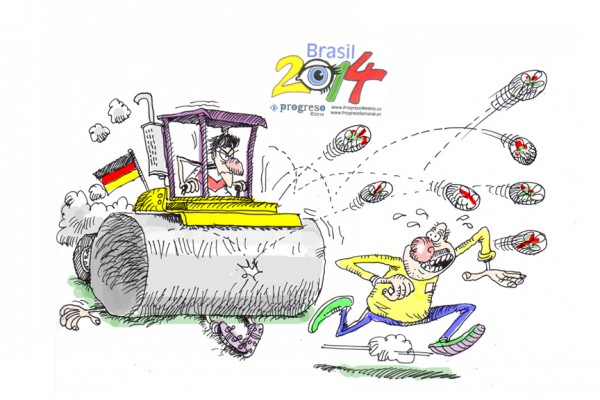

None of the things that might have sufficed to make this World Cup a memorable event will be remembered in the future after the 7-1 the other night at the Minerão.

This World Cup, the best of the ones I’ve seen, will go into history because of the drubbing that Germany inflicted on Brazil, the worst defeat a team has ever had in the semifinals and, as if that weren’t enough, on its home turf.

This World Cup, the best of the ones I’ve seen, will go into history because of the drubbing that Germany inflicted on Brazil, the worst defeat a team has ever had in the semifinals and, as if that weren’t enough, on its home turf.

As expected, after the tears, the lamentations and the clenched fists raised skyward, came the witch hunt. The masses, still in a daze, began to ask for the names of culprits, for some head they might chop. From the TV screen, the press, and the social networks (the game was the most tweeted sports event ever, with 35.6 million publications), fingers were pointed in all directions.

The fans criticized Felipão’s conservatism, the betrayal of the “jogo bonito” that began back in the 1990 World Cup, the sequels of Dunga’s openly defensive vocation, Neymar’s injury and Thiago Silva’s yellow card — although I think that Zúñiga and the referee did a favor to both by saving them from humiliation.

Criticism was intensified of an event already much questioned: stadiums of exaggerated size, a total cost of about 8.2 billion euros, about 250,000 people (mostly indigenous natives) displaced. Even the legendary Romário, today a federal deputy, accused the Brazilian Soccer Federation of being corrupt.

Even here in Miami, where World Cup fever is felt at intervals, many people howled for blood. Brazil’s fans, who, by birth or adoption are a majority, seem to have slunk away. No longer do you see green-and-yellow flags or jerseys.

Only the Argentines appear happy. Even Maradona sneered on his TV program “De zurda.” In truth, I don’t understand why — especially after the game with Holland, where the heroes were not Messi or Lavezzi or Higuaín, but Mascherano and Chiquito Romero. If I were an Argentine, my laughter would be more of a nervous chortle.

One of the few who appear to remain lucid is Argentine writer Hernán Casciari, who wrote in his blog: “We can hope to beat Brazil. We can wish that Brazil will always lose, in overtime if possible. We can point out, sarcastically, that, even though the Brazilians won five World Cups, they’ve never won one at home. But to wish them or to celebrate a 7-to-1 against Germany, knowing that the next prey of the ferocious machines could be us … that is not desirable.”

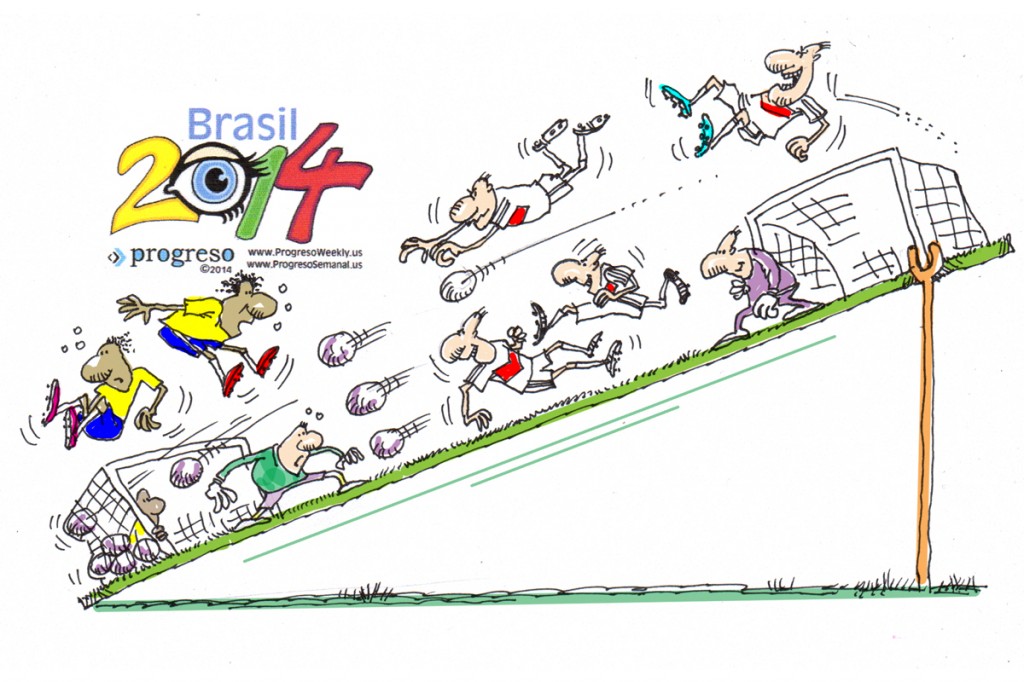

What troubles me the most is that everybody talks about the misfortune, the humiliation, and Brazil’s soccer crisis, but little has been said — at least around this part of the world — about Germany’s precision. The more I see the Germans play, the less they fit the stereotype of the cold, heartless machines that play soccer as if it were a math calculation, an algorithm.

Maybe they are, but in the precision of their passes, in their defensive effectiveness, in the verticality of their lightning attacks there is also beauty and, overall, intense passion. If not, somebody should explain to me what soccer is.

The game the Germans play has a little of South American soccer and a lot of the “totaal voetbal” of Johann Cruyff’s Clockwork Orange — the real one, not this faded version with very inspired second halves — without losing that essential creed that makes them attack at all times, onward to the end, until the referee blows his whistle. The idea that “if we can score three goals, why not four or five? And, who knows, maybe even seven.”

Later, only later, come the records, Klose’s 16 goals, the 69 seconds that separated Toni Kroos two scores, the five goals before the game was 30 minutes old. Germany might lose on Sunday, maybe Messi will be inspired, as geniuses often are, and will give us a final like the one in 1986, but Germany will remain — by a wide margin — the best team I’ve seen in this World Cup.

The odd thing is that this began, in part, after Germany was trounced — not 7 to 1, true, but trounced nevertheless — out of the groups phase in the 2000 Eurocup organized by Belgium and Holland. After that disaster, the German Soccer Federation implemented a program to rejuvenate the national team, a plan that encouraged all the teams in the Bundesliga to create academies with superb infrastructures to train boys between the ages of 9 and 19.

That was the cradle for many of the players coached by Jurgen Klinsmann (who is trying to do something similar in the U.S.), who later trained with Joachim Löw’s litter — Müller, Kroos, Ozil, Khedira and many other weird names — without a generational gap being noticed.

This philosophy was summarized better than anyone by Mauro Germán Camoranesi — another of the pleasant surprises in the World Cup, at least to those of us who watched him on Univisión — who, in addition to being a swift and skillful forward has turned out to be a lucid, measured, and objective analyst, i.e., the last thing one would expect from a former soccer player.

Between the German goals, Camoranesi said that a German journalist had told him that soccer execs in his country were very concerned because they don’t see any player in the minor leagues with the necessary qualities to replace those in the current national team. In other words, they still have players sufficiently young to play in two more World Cups, yet they’re worrying about the next generation.

How beneficial it would be for us, I thought, to get an injection of that kind of mentality, even if it’s only a bit of that post-war philosophy. It would be useful if, in place of looking for culprits, undoing wrongs, and perpetrating vengeance, we would concentrate on finding solutions for the future.

Obviously, I’m talking about something that transcends sports. Or maybe not. I don’t know. Nowadays, few things make me as happy, or are as important to me as soccer, even if my teams sooner or later end up losing.

[In our Graphite n’ Ink section you can see our collection of illustrated postcards that Progreso Weekly updates after each World Cup match.]