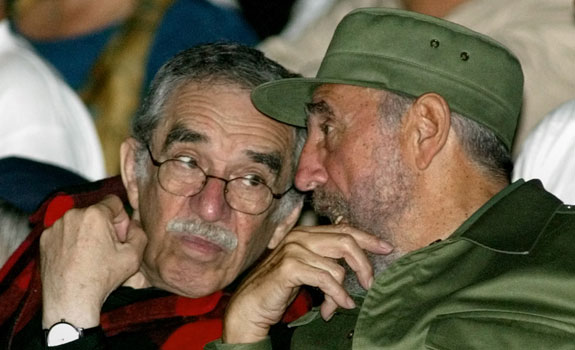

A passion named Fidel

By Mauricio Vicent

The first time Gabriel García Márquez heard the name of Fidel Castro was in 1955.

At that time, the writer shared exile in Paris with a group of Latin American intellectuals and each awaited the fall of his own dictator. So, when one morning Cuban poet Nicolás Guillén opened the window in his room and shouted, “The man fell!” everyone thought the ousted dictator was his.

The Paraguayans thought that it was Stroessner; the Nicaraguans, Somoza; the Colombians, López Pinilla; the Dominicans, Trujillo, and so on, an interminable list. At the end, it turned out to be Juan Domingo Perón, and a little later, chatting about the incident, Guillén confessed to García Márquez that he didn’t have much hope of seeing the end of Batista in Cuba.

That’s when the poet spoke to him for the first time about a young man named Fidel who had just been released from prison after raiding the Moncada army barracks.

Three years later, García Márquez was in Caracas, living as a reporter the first year of Venezuela without Marcos Pérez Jiménez, when the news came of Castro’s triumph. Two weeks later, he and Plinio Apuleyo Mendoza boarded a plane with a group of journalists headed for Havana.

García Márquez would end up as part of the foundational nucleus of the Prensa Latina agency, created in summer of 1959 by Jorge Ricardo Masetti and Che Guevara. Since then, García Márquez’s relationship with Cuba and Fidel Castro became almost one and the same, because the island and his friendship with the Cuban leader were, to him, inseparable elements.

“The first time I saw him with these merciful eyes was in that big and uncertain year of 1959, when he was convincing an employee at the Camagüey Airport to always have a chicken in the refrigerator, so the gringo tourists would reject the imperialist lie that ‘we Cubans are dying of hunger,'” García Márquez said about his first encounter with Castro.

As a journalist with Prensa Latina at first, and as a defender of the revolution throughout the world after he became a famous writer, as years passed, García Márquez forged a very special relationship of friendship with the Cuban leader, to the point that he became Castro’s confessor and literary adviser, his accomplice as a mediator in conflicts in the region and even his envoy in a secret mission to the United States during the administration of Bill Clinton.

As García Márquez and his wife Mercedes began to travel to Cuba with more frequency, Castro placed at his disposal one of the luxurious protocol residences in the Cubanacán district of Havana. The mansion immediately became a place for reunion and conspiracy, an activity they both loved and cultivated extensively so long as they were healthy.

On one of those dusk-to-dawn meetings at a table in the garden, Castro and the Colombian writer conceived the adventure of creating a school of cinema and television for Third World students that might serve to counterbalance “imperialist cinematography.”

Thus was born in 1985 the Foundation for New Latin American Cinema under the Nobel laureate’s direction. One year later, a school was created, where García Márquez taught a script-writing course that became legendary: “How To Tell a Story.” Francis Ford Coppola, Robert Redford and [Konstantinos] Costa-Gavras were some of the filmmakers who participated in the school’s workshops, courses and seminars.

In Cuba, the author of “One Hundred Years of Solitude” cultivated all kinds of friends, from filmmakers like Julio García Espinosa to comandantes like the legendary Barbarroja, Manuel Piñeiro, for years the man responsible for the organization of, and support for, the guerrillas and liberation movements in Latin America.

But that house, more than anything else, was a refuge for Fidel, who visited Gabo without prior notice, most times at dawn, to talk about anything for hours at a time. “Sometimes he whooshed in like a hurricane, outrageously hungry,” the writer told. “Once, he ate 28 scoops of ice cream.”

Gabo’s privileged relationship allowed him to mediate with Castro on the most dissimilar issues, from removing from the island the writer Norberto Fuentes (a friend of Tony La Guardia and Arnaldo Ochoa, Cuban officers executed in 1989) to getting a fellow journalist an interview with Fidel.

During the Fourth Ibero-American Summit in Cartagena de Indias, in 1994, Gabo rode with his friend in a horse-drawn carriage despite an assassination threat against the Cuban leader. Four years later, when Pope John Paul II visited the island, Castro invited the writer to sit next to him during the Mass that the pontiff officiated on Revolution Square before a million Cubans.

Gabo also carried out discreet missions with Clinton during the 1994 rafters’ crisis, in the course of a summer dinner with the former president at the home of writer William Styron in Martha’s Vineyard. In 1997, after bomb attacks against several hotels in Havana, he acted as a courier for Castro and delivered a message to Clinton that enabled both countries to establish secret deals for anti-terrorist cooperation that lasted a while.

At his home in Havana, along with works by great Cuban painters like Victor Manuel and Amelia Peláez, García Márquez had a painting done by Tony La Guardia and presented to him by the officer. The Colombian writer, who had been La Guardia’s friend, did not remove the oil painting from the wall after La Guardia was executed for treason.

In Cuba, Gabo had a special dispensation. In public and private, he criticized the bureaucracy and many things about Cuban socialism that he didn’t like. But always, ever since he first saw him convincing an employee at Camagüey Airport, he was faithful to his friend Fidel.

(From the Spanish newspaper El País)

Translation by Progreso Weekly