America’s stupidest foreign policy: isolating Cuba

By Robert Shrum

Facing a House of Representatives frozen in its own ideology, Barack Obama is relying on executive action: first to raise the minimum wage for new federal contract workers and soon to impose new limits on carbon emissions. Some observers see this as an implicit admission of a presidency in twilight. In reality, Obama can and should act in history-making ways, at home on issues like climate change, and overseas on the longest, if not the dumbest, American foreign-policy mistake, just 90 miles from our shores.

The attempted isolation of Cuba, the vain resolve to overthrow or punish the Castro regime, has been perpetuated for over half a century by presidents of both parties. Granted, Jimmy Carter, Bill Clinton, and Obama have each ventured a measure of détente without fundamentally reversing a course that has brought only persistent failure. And in the mid-1990s, when the Cuban Air Force shot down two airplanes dispatched by a Miami – based exile group, Brothers to the Rescue, which had previously dropped hundreds of thousands of leaflets over Havana, the United States reverted to a hard anti–Castro line. Congress passed the Helms–Burton Act to tighten the sanctions regime and write it into the law. Democratic opposition had blocked the bill in 1995, but in the wake of attack Bill Clinton, anxious to carry Florida in his reelection bid, swiftly signed it into law. Most Democratic presidents – and perhaps secretly even George H.W. Bush – have understood the folly of U.S. policy toward Cuba. Ironically, John F. Kennedy, who had tried overtly and covertly to topple Castro, seemed to be moving in a decisively different direction by 1963. He dispatched unofficial envoys to discuss rapprochement; one of them, French journalist Jean Daniel, was with Fidel Castro when the news of Kennedy’s assassination came. “This is terrible,” Castro exclaimed. “There goes your mission of peace.” Not long after, normalizing relations with Castro would become a third rail in politics with pivotal Florida in the sway of a growing population of violently anti-Castro Cuban-American citizens.

Thus Cuba morphed into the cold war that has outlasted the Cold War. Seldom if ever has any foreign-policy toward any country endured across decades without any rational basis to believe it will ever succeed. Even the delusion of isolating China, fed by paranoia and demagoguery, was dispensed with in less than 25 years–and by the fervently anti-communist Richard Nixon, who decided it was time to get real. It is long past time to get real about Cuba. I was there for ten days last month, the first time I had returned since a trip to Havana in the 1970s with Senator George McGovern. Yes, there are dissidents; there is repression. But there is also palpable pride in the revolution, which overthrew an American–blessed regime presiding over a corrupt, gangster–ridden economy that lavished wealth on the few and impoverished the vast majority. That Cuba was no free society. As one Cuban put it, the revolution was one of the few times in history when the underdog triumphed against all the odds. Nor is there any sign that the passing of Castro, who has outlasted generations of American adversaries and the disappearance of his Soviet allies, will trigger a counter-revolution. While his record, even on his own terms, is mixed, there are social reforms that ordinary Cubans prize – and would not be willing to jeopardize.

Education and literacy, once denied to so many, are universal. So are retirement benefits. And there has been a sustained revolution in health care. The CIA World Factbook reports that Cuban life expectancy approximates life expectancy in the U.S.–and infant mortality is measurably lower. Critics question the reliability of the data, but in any event, Cuba is far better off in standard measures of health than most of Latin America.

On the other hand, the economic model is as threadbare as many of the buildings and much of the island’s infrastructure. Cuba lost $13 billion a year in subsidies and export sales with the fall of the Soviet Union. The Venezuela of the late Hugo Chavez, now in turmoil, which sends in cut-rate oil, can’t be permanently relied on. Castro himself, who once scorned tourism as a vestige of the old order, did a complete about-face, describing it as “gold” after the withdrawal of Soviet largesse. There is now a rising tide of tourism – from Canada, Europe, and Asia – along with a modest wave of Americans who have to travel with an official license as part of an educational or cultural trip. If Americans could travel to Cuba freely, their numbers could swell to 1 million and then 2 million a year– and U.S. companies, not just the British or German or Spanish ones who are there already, could build the hotels of the future. Tourism by itself can’t resolve the country’s economic problem – and tourism both alleviates and exacerbates it. It is difficult to grow and prosper when a bellhop or a tour guide can earn more in tips in the day than a doctor makes in a month, which is why doctors and others have opened house restaurants throughout the island. Lifting or easing American sanctions wouldn’t be a deus ex machina either, even if it relieved shortages of basic goods like soap and toilet paper. The Castro regime itself has to embark on new reforms, and that’s happening. Cubans can now start not only house restaurants, but their own small businesses. Fidel’s brother Raul, the country’s new president, has proposed a law to permit large-scale foreign investment across the Cuban economy, even in the formerly off – limits agricultural sector. There is no doubt the law will pass – and there is every prospect it will achieve its goals of “attract[ing] foreign capital, generat[ing] new jobs, and bolster[ing] domestic industry.” The Europeans will be there. So will Canadian, Asian, and Latin American investors. Only U.S. companies will be locked out – not by Cuba, but by our own government. This isn’t a policy in any coherent sense of that word; it’s an artifact of resentment, a self-defeating relic from another era. But what about Cuba’s human-rights violations? There are far more pervasive and egregious abuses in other nations with which we routinely do business like China and Russia. Obama has said the embargo could be lifted under certain conditions, including democratic elections for the Cuban presidency. We don’t make a similar demand, or impose similar penalties, on Egypt, China, Saudi Arabia or a host of countries that conduct Potemkin elections. Indeed, a greater American presence on the island is far more likely than isolation to foster liberalization in a society where, as a Cuban said to me, “We can think or mostly say what we want; we just can’t act.” According to a new poll conducted for the Atlantic Council by Democrat Paul Maslin and Republican Glen Bolger, 56 percent of Americans and 63 percent of Floridians support “normalizing relations or engaging more directly with Cuba.” Surprisingly, 52 percent of Republicans agree, and so do 64 percent% of residents of Miami-Dade County, the center of the Cuban diaspora. It is telling that sugar magnate Alfonso Fanjul, who fled Cuba after the revolution, now says he’s ready to invest there “under the right circumstances.” He has already visited the island several times and argues that the U.S. and Cuba should “find a way” for “the whole Cuban community to live and work together.” Without the Elian Gonzalez controversy – when the Clinton administration returned a young child to Cuba after his mother drowned trying to reach Florida– Al Gore almost certainly would have won the state by enough votes so he could not have been counted out of the presidency by virtue of a confusing butterfly ballot in Palm Beach County or a Supreme Court majority that acted like a GOP ward committee. But the political landscape will not be the same in 2016. Obviously, Obama won’t be seeking reelection– and the Atlantic Council numbers mean that he and other Democrats don’t have to worry that Hillary Clinton, the inevitable nominee, will lose Florida if the U.S. regains its senses and renounces the cold war with Cuba. The president, of course, can’t do it all on his own; Helms–Burton codifies the embargo. But the Cuba Study Group outlines eleven measures Obama can take– such as authorizing “more imports of certain goods and services,” permitting “the sale of telecommunications hardware,” and removing the absurd designation of Cuba as “a state sponsor of terrorism.” It’s undeniable that this Congress won’t come to its senses; it’s indisputable that the president can – and should – act. The bitter-end exile movement, as the Atlantic Council poll demonstrates, now has a markedly diminished hold on Miami and the Cuban-American community. Still there was predictable fury when Barack Obama refused to conspicuously insult Raul Castro at Nelson Mandela’s funeral and instead shook his hand. Senator Marco Rubio blasted Obama– and the reliably obnoxious Ted Cruz, who was part of the official delegation to the funeral, walked out when Castro spoke. For the sake of a sane foreign-policy, the president should now make Rubio, Cruz, and their ilk even angrier by reaching out his hand again – and with the stroke of a pen, begin to end the most protracted foreign policy failure in our history.

Robert Shrum, who was a senior fellow at NYU and has now been appointed Warschaw Professor of the Practice of Politics at the University of Southern California, was a longtime political consultant. He worked on numerous Democratic campaigns, including Kerry-Edwards in 2004 and Al Gore’s 2000 race for the White House.

(From The Daily Beast)

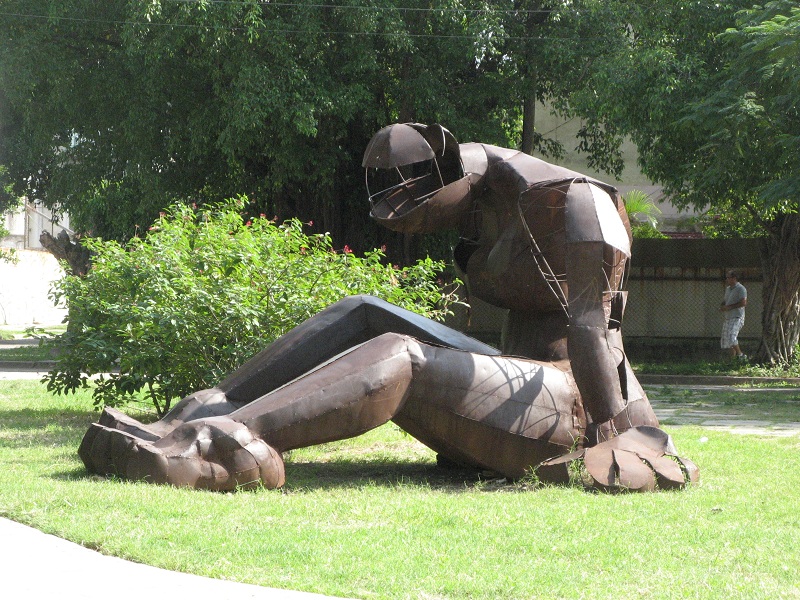

[Photo is of art found in the Lam Park in the Vedado neighborhood of Havana. From Ecopolitics Today blog.]