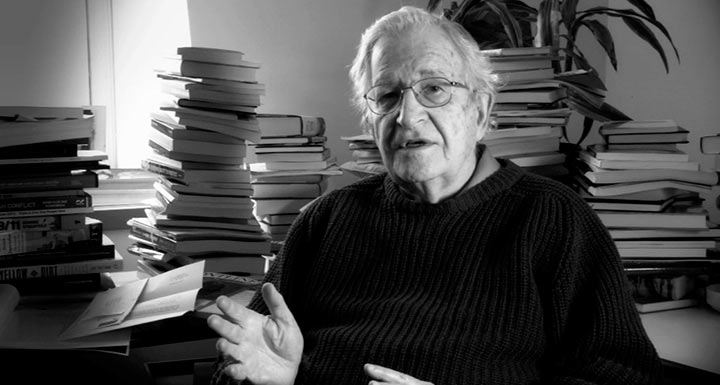

Noam Chomsky: Why Americans know so much about sports but so little about world affairs

The following is a short excerpt from a classic, The Chomsky Reader, which offers a unique insight on a question worth asking — how is it that we as a people can be so knowledgable about the intricacies of various sports teams, yet be colossally ignorant about our various undertakings abroad?

QUESTION: You’ve written about the way that professional ideologists and the mandarins obfuscate reality. And you have spoken — in some places you call it a “Cartesian common sense” — of the commonsense capacities of people. Indeed, you place a significant emphasis on this common sense when you reveal the ideological aspects of arguments, especially in contemporary social science. What do you mean by common sense? What does it mean in a society like ours? For example, you’ve written that within a highly competitive, fragmented society, it’s very difficult for people to become aware of what their interests are. If you are not able to participate in the political system in meaningful ways, if you are reduced to the role of a passive spectator, then what kind of knowledge do you have? How can common sense emerge in this context?

CHOMSKY: Well, let me give an example. When I’m driving, I sometimes turn on the radio and I find very often that what I’m listening to is a discussion of sports. These are telephone conversations. People call in and have long and intricate discussions, and it’s plain that quite a high degree of thought and analysis is going into that. People know a tremendous amount. They know all sorts of complicated details and enter into far-reaching discussion about whether the coach made the right decision yesterday and so on. These are ordinary people, not professionals, who are applying their intelligence and analytic skills in these areas and accumulating quite a lot of knowledge and, for all I know, understanding. On the other hand, when I hear people talk about, say, international affairs or domestic problems, it’s at a level of superficiality that’s beyond belief.

In part, this reaction may be due to my own areas of interest, but I think it’s quite accurate, basically. And I think that this concentration on such topics as sports makes a certain degree of sense. The way the system is set up, there is virtually nothing people can do anyway, without a degree of organization that’s far beyond anything that exists now, to influence the real world. They might as well live in a fantasy world, and that’s in fact what they do. I’m sure they are using their common sense and intellectual skills, but in an area which has no meaning and probably thrives because it has no meaning, as a displacement from the serious problems which one cannot influence and affect because the power happens to lie elsewhere.

Now it seems to me that the same intellectual skill and capacity for understanding and for accumulating evidence and gaining information and thinking through problems could be used — would be used — under different systems of governance which involve popular participation in important decision-making, in areas that really matter to human life.

There are questions that are hard. There are areas where you need specialized knowledge. I’m not suggesting a kind of anti-intellectualism. But the point is that many things can be understood quite well without a very far-reaching, specialized knowledge. And in fact even a specialized knowledge in these areas is not beyond the reach of people who happen to be interested.

…

QUESTION: Do you think people are inhibited by expertise?

CHOMSKY: There are also experts about football, but these people don’t defer to them. The people who call in talk with complete confidence. They don’t care if they disagree with the coach or whoever the local expert is. They have their own opinion and they conduct intelligent discussions. I think it’s an interesting phenomenon. Now I don’t think that international or domestic affairs are much more complicated. And what passes for serious intellectual discourse on these matters does not reflect any deeper level of understanding or knowledge.

One finds something similar in the case of so-called primitive cultures. What you find very often is that certain intellectual systems have been constructed of considerable intricacy, with specialized experts who know all about it and other people who don’t quite understand and so on. For example, kinship systems are elaborated to enormous complexity. Many anthropologists have tried to show that this has some functional utility in the society. But one function may just be intellectual. It’s a kind of mathematics. These are areas where you can use your intelligence to create complex and intricate systems and elaborate their properties pretty much the way we do mathematics. They don’t have mathematics and technology; they have other systems of cultural richness and complexity. I don’t want to overdraw the analogy, but something similar may be happening here.

The gas station attendant who wants to use his mind isn’t going to waste his time on international affairs, because that’s useless; he can’t do anything about it anyhow, and he might learn unpleasant things and even get into trouble. So he might as well do it where it’s fun, and not threatening — professional football or basketball or something like that. But the skills are being used and the understanding is there and the intelligence is there. One of the functions that things like professional sports play, in our society and others, is to offer an area to deflect people’s attention from things that matter, so that the people in power can do what matters without public interference.

QUESTION: I asked a while ago whether people are inhibited by the aura of expertise. Can one turn this around — are experts and intellectuals afraid of people who could apply the intelligence of sport to their own areas of competency in foreign affairs, social sciences, and so on?

CHOMSKY: I suspect that this is rather common. Those areas of inquiry that have to do with problems of immediate human concern do not happen to be particularly profound or inaccessible to the ordinary person lacking any special training who takes the trouble to learn something about them. Commentary on public affairs in the mainstream literature is often shallow and uninformed. Everyone who writes and speaks about these matters knows how much you can get away with as long as you keep close to received doctrine. I’m sure just about everyone exploits these privileges. I know I do. When I refer to Nazi crimes or Soviet atrocities, for example, I know that I will not be called upon to back up what I say, but a detailed scholarly apparatus is necessary if I say anything critical about the practice of one of the Holy States: the United States itself, or Israel, since it was enshrined by the intelligentsia after its 1967 victory. This freedom from the requirements of evidence or even rationality is quite a convenience, as any informed reader of the journals of public opinion, or even much of the scholarly literature, will quickly discover. It makes life easy, and permits expression of a good deal of nonsense or ignorant bias with impunity, also sheer slander. Evidence is unnecessary, argument beside the point. Thus a standard charge against American dissidents or even American liberals — I’ve cited quite a few cases in print and have collected many others — is that they claim that the United States is the sole source of evil in the world or other similar idiocies; the convention is that such charges are entirely legitimate when the target is someone who does not march in the appropriate parades, and they are therefore produced without even a pretense of evidence. Adherence to the party line confers the right to act in ways that would properly be regarded as scandalous on the part of any critic of received orthodoxies. Too much public awareness might lead to a demand that standards of integrity should be met, which would certainly save a lot of forests from destruction, and would send many a reputation tumbling.

The right to lie in the service of power is guarded with considerable vigor and passion. This becomes evident whenever anyone takes the trouble to demonstrate that charges against some official enemy are inaccurate or, sometimes, pure invention. The immediate reaction among the commissars is that the person is an apologist for the real crimes of official enemies. The case of Cambodia is a striking example. That the Khmer Rouge were guilty of gruesome atrocities was doubted by no one, apart from a few marginal Maoist sects. It is also true, and easily documented, that Western propaganda seized upon these crimes with great relish, exploiting them to provide a retrospective justification for Western atrocities, and since standards are nonexistent in such a noble cause, they also produced a record of fabrication and deceit that is quite remarkable. Demonstration of this fact, and fact it is, elicited enormous outrage, along with a stream of new and quite spectacular lies, as Edward Herman and I, among others, have documented. The point is that the right to lie in the service of the state was being challenged, and that is an unspeakable crime. Similarly, anyone who points out that some charge against Cuba, Nicaragua, Vietnam, or some other official enemy is dubious or false will immediately be labeled an apologist for real or alleged crimes, a useful technique to ensure that rational standards will not be imposed on the commissars and that there will be no impediment to their loyal service to power. The critic typically has little access to the media, and the personal consequences for the critic are sufficiently annoying to deter many from taking this course, particularly because some journals — the New Republic, for example — sink to the ultimate level of dishonesty and cowardice, regularly refusing to permit even the right of response to slanders they publish. Hence the sacred right to lie is likely to be preserved without too serious a threat. But matters might be different if unreliable sectors of the public were admitted into the arena of discussion and debate.

The aura of alleged expertise also provides a way for the indoctrination system to provide its services to power while maintaining a useful image of indifference and objectivity. The media, for example, can turn to academic experts to provide the perspective that is required by the centers of power, and the university system is sufficiently obedient to external power so that appropriate experts will generally be available to lend the prestige of scholarship to the narrow range of opinion permitted broad expression. Or when this method fails — as in the current case of Latin America, for example, or in the emerging discipline of terrorology — a new category of “experts” can be established who can be trusted to provide the approved opinions that the media cannot express directly without abandoning the pretense of objectivity that serves to legitimate their propaganda function. I’ve documented many examples, as have others.

The guild structure of the professions concerned with public affairs also helps to preserve doctrinal purity. In fact, it is guarded with much diligence. My own personal experience is perhaps relevant. As I mentioned earlier, I do not have the usual professional credentials in any field, and my own work has ranged fairly widely. Some years ago, for example, I did some work in mathematical linguistics and automata theory, and occasionally gave invited lectures at mathematics or engineering colloquia. No one would have dreamed of challenging my credentials to speak on these topics — which were zero, as everyone knew; that would have been laughable. The participants were concerned with what I had to say, not my right to say it. But when I speak, say, about international affairs, I’m constantly challenged to present the credentials that authorize me to enter this august arena, in the United States, at least — elsewhere not. It’s a fair generalization, I think, that the more a discipline has intellectual substance, the less it has to protect itself from scrutiny, by means of a guild structure. The consequences with regard to your question are pretty obvious.

QUESTION: You have said that most intellectuals end up obfuscating reality. Do they understand the reality they are obfuscating? Do they understand the social processes they mystify?

CHOMSKY: Most people are not liars. They can’t tolerate too much cognitive dissonance. I don’t want to deny that there are outright liars, just brazen propagandists. You can find them in journalism and in the academic professions as well. But I don’t think that’s the norm. The norm is obedience, adoption of uncritical attitudes, taking the easy path of self-deception. I think there’s also a selective process in the academic professions and journalism. That is, people who are independent minded and cannot be trusted to be obedient don’t make it, by and large. They’re often filtered out along the way. […]

From The Chomsky Reader, as published on Noam Chomsky’s personal site. (Serpents Tail Publishing, 1988). / From the: Altern Net