When MLK was killed, he was in Memphis fighting for economic justice

By Debbie Elliott

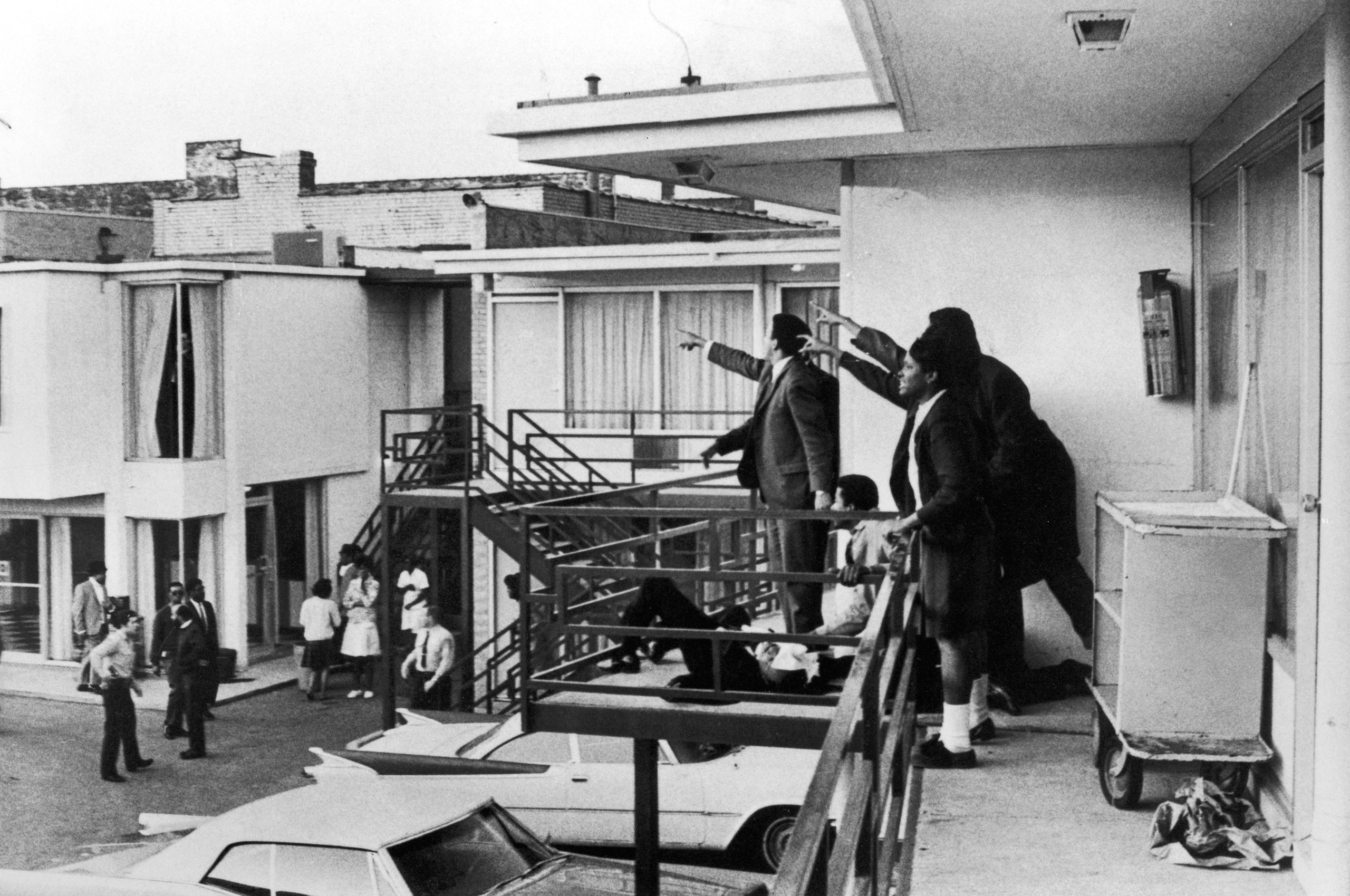

It was a call for help from activists that took the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. to Memphis in March 1968. Days later he would be fatally shot by James Earl Ray on the balcony of the Lorraine Motel.

But before the motel, the shooting, the riots and the mourning, there was the Memphis sanitation workers’ strike.

King broke away from his work on the Poor People’s Campaign to travel from Atlanta to Tennessee and help energize the strikers — his last cause for economic justice.

Fifty years later, Elmore Nickelberry is one of the last strike participants still on the job with the Memphis Sanitation Department. He’s 86 and his night shift starts at the “barn” — mostly a giant parking lot full of garbage trucks.

Today he’s a driver with a crew of two, and his truck is equipped to lift and dump trash bins. Back in the ’50s and ’60s, he did the lifting and dumping.

“When I first started it was rough,” he says. “I had to tote tubs on my head, on my shoulders, under my arms.”

He rode on the back of truck, jumping off to go into people’s back yards to pick up garbage. It was a filthy, and often thankless job.

Nickelberry says the trash tubs would leak, dripping onto his clothes. Sometimes he would have to climb into the back of the truck to help load the garbage.

“And when I’d load the truck there would be maggots in my shoes,” says Nickelberry.

But the city didn’t let African-American workers shower at the barn – that was reserved for the white drivers. And there was no place for them to take shelter in the rain. In early 1968 trash collectors Echol Cole and Robert Walker climbed into the back of a truck to escape a storm, and were accidently crushed to death by its compactor.

In response, workers organized to demand better working conditions and higher pay. Nickelberry says they had no respect.

“Most of the time they’d call us boys,” he says. “Or we’d get on the bus and they’d say ‘look at that old garbage man.’ And I knew I wasn’t no garbage man. I just worked in garbage.”

Then Mayor Henry Loeb rejected the workers’ demands, refusing to recognize their union. They walked off the job. Nickelberry says they marched downtown every morning, wearing sandwich boards and carrying placards that declared “I Am A Man.”

The heart of racism

The strike was supported by local clergy active in the civil rights movement. A key organizer was the Rev. James Morris Lawson Jr., pastor of Centenary Methodist Church in Memphis at the time.

He helped map strategy for the sanitation workers strike, and spoke out against the city’s leadership.

“When a public official orders a group of men to ‘get back to work and then we’ll talk’ and treats them as though they are not men, that’s a racist point of view,” he said in 1968. “For at the heart of racism is the idea that a man is not a man.”

“I used some of the movement’s language that you were men. You’re a child of God. You are somebody,” recalls Lawson, now 89 and living in Los Angeles.

“Segregation tries to pretend that you’re not a human being. You’re not a man like that. You have to fight that as you have now engaged in this struggle. You yourselves must claim your humanity before God.”

Lawson had studied Ghandi’s non-violent methods as a missionary in India, and had come South at the urging of King.

“The climate in Memphis was that of a pretty fierce racism,” he says.

There were no black supervisors at the sanitation department, and wages were so meager many of the workers used food stamps to eat. They called the public works barn “the plantation.”

The strike was languishing, so to help galvanize support in the broader black community, Lawson invited King to come speak.

“When I called him, King immediately said ‘of course, yes,'” Lawson says.

King’s last march

The strike was all but broken until King got involved, according to Fred Davis, a Memphis city councilman at the time.

“Dr. King’s presence gave some buoyancy to the sanitation workers,” Davis says. “But on the other hand it stiffened the resistance in the white community.”

Davis had just taken office in January of 1968 — one of the city’s first three African-American councilmen. He was chairman of the public works committee, which oversaw the sanitation department. But he sided with the workers in their fight with the city.

“That’s me and him on his last march,” Davis says as he looks at a photograph taken on March 28. In it, a young Davis is standing near King, a crowd following behind. Davis says as the march rounded Beale Street, a group of young men broke away.

“They started throwing bricks into the windows of the businesses and taking sticks and breaking the windows out,” Davis says. “And then all hell broke loose and the police moved in with tear gas and nightsticks.”

He says he and another black councilman were accosted by police in the melee. “We tried to explain to them we were a member of the city council,” Davis says. “And they replied they didn’t give a damn.”

The march was turned back, and organizers took King to safety, fearing he would be targeted. Police killed a 16-year-old suspected of looting. Dozens of people were injured. And more than 250 arrested.

“It came apart,” Davis says. “And Dr. King was very disappointed.”

By nightfall, the Tennessee legislature enacted a state of emergency, armored tanks rolled into town with some 3,800 National Guard troops, and Mayor Loeb set a curfew.

“When the march … degenerated into a riot, abandoned by its leaders, the police with my full sanction, took the necessary action to restore law and order,” Loeb said at the time.

King joined organizers for a news conference that evening where they said the marches would continue.

“Since the unfortunate developments today took place,” King said, “I’ll probably have to stay longer than I originally planned.”

“The nation is sick”

King returned in early April.

The only African-American church sanctuary in Memphis large enough to accommodate the crowd that wanted to hear King on April 3, 1968, was Mason Temple, home to the Church of God in Christ.

“We felt a kindredness, a relationship with him and with the civil rights movement,” says Presiding Bishop Charles Blake as he walks across vivid red carpet to the pulpit where King preached for the last time. “We were overjoyed to open our doors for the rally on that night.”

“Nothing would be more tragic than to stop at this point in Memphis,” King said during the mass meeting.

“The nation is sick,” he said. “Trouble is in the land.”

After spending more than a decade trying to dismantle segregation, King had turned his focus to poverty. He was organizing the Poor People’s Campaign when the Rev. James Lawson asked him to come to Memphis. Lawson says the sanitation workers’ plight was a natural fit with his new mission.

But the city of Memphis did not like the attention that King’s presence brought. After the violent demonstration on March 28, city officials were seeking a court injunction to prevent King from leading another march on April 5.

“Certainly, a large part of the white community in Memphis was alarmed and afraid, and on the verge of hysteria about possible civil disorder,” says local attorney Charles Newman who was part of the legal team hired by King and the SCLC to fight the injunction.

Newman says they had a strong legal argument for the march to proceed.

“I think the subtext was that the chances of civil disorder were higher if the march were enjoined than if it were allowed,” Newman says.

King was being attacked for the violence in Memphis, says Clayborne Carson, director of the Martin Luther King Research and Education Institute at Stanford University, and the editor of King’s papers.

“He knew that if he didn’t respond and show that he could have a peaceful march in Memphis then what were the prospects for his Poor People’s Campaign in Washington and particularly in that volatile environment of ’67, ’68?” Carson says. “You know there were signs that the country was coming apart on racial lines.”

“I’ve been to the mountaintop”

A spring thunderstorm was dousing Memphis the night of April 3. King was doubtful people would show for the mass meeting at Mason Temple so, at first, he stayed behind at the Lorraine Motel.

But the sanctuary was full to the balconies, and the crowd called out to hear from King, according to former councilman Fred Davis.

“He came in and sat in the chair for a minute just to catch his breath and then he approaches the podium. He had no notes or nothing,” Davis says. “He was in the Spirit.

“We’ve got some difficult days ahead. But it really doesn’t matter with me now, because I’ve been to the mountaintop,” King preached to rousing applause.

“For me it was one of the zenith experiences of the whole campaign, the whole movement,” says Rev. Lawson.

“It was thundering and lightning outside and we had a tin roof in part of the Mason Temple. And so the rain was just battering the roof. Nevertheless there was a sense inside of warmth and unity. We’re engaged in a great struggle.”

King continued:

“I’ve seen the Promised Land. I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight, that we, as a people, will get to the Promised Land! And so I’m happy, tonight. I’m not worried about anything. I’m not fearing any man. Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord!”

The next day, James Earl Ray shot and killed Martin Luther King.

“America is shocked and saddened by the brutal slaying tonight of Dr. Martin Luther King,” President Lyndon B. Johnson said on the night of April 4, calling for calm. “I ask every citizen to reject the blind violence that has struck King, who lived by non-violence.”

But riots broke out – in Memphis and around the country.

Rev. Lawson says momentum for transforming the country was lost to what he calls “the politics of assassination.”

“That has continued to grieve me his death whatever it was going to happen,” Lawson says. “It happened in Memphis. Wherever was going to happen that still grieves me because of what it did to the nation, the loss.”

Lawson is still teaching non-violent strategies to young activists. He’s not lost hope.

“There are a lot of signs that a lot of people want to get back on the track. The women’s marches, the Dreamers marches, the immigration people, the work to dismantle the criminal justice system.”

Sanitation worker Elmore Nickelberry drives by the Lorraine Motel on his downtown trash route. “He got shot right up there,” he says. “You can see where he stood on the balcony right there.”

Nickelberry says he’ll never forget what King did.

“Martin Luther come to Memphis to help the sanitation department. And then the man get killed,” he says. “I don’t like to talk about it. You feel mighty bad a man come to help you and then he [gets] killed. That’s bad.”

After King’s assassination, the city settled with striking workers, and recognized their union. They got showers, uniforms, higher wages and African-American supervisors.

Today that same union – the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees – is still advocating for Memphis sanitation workers.

They were part of a working people’s day of action recently at Clayborn Temple – the historic building where sanitation workers organized in 1968.

The crowd chanted “I am a man!”

“The issues today are safe working conditions and those critical four words that we spoke 50 years ago,” says Maurice Spivey, the union chapter chairperson for Memphis sanitation workers.

Spivey says among other things, they’re advocating for air conditioning in the garbage trucks, a pay raise, and benefits for temporary employees.

Cleophus Smith is one of the original strikers. The 75-year-old sanitation worker says they just want pay and benefits more in line with other city employees.

“I make about $18 an hour and that’s all I’ve been making for the last nine years,” Smith says.

Activists say the issue of economic justice that King was pursuing remains relevant in Memphis – a majority black city where the poverty rate for African-Americans is double that of the white population.

P. Moses, a Memphis organizer with Black Lives Matter, says the movement shares common ground with “I am a man.”

“One is a cry and the other is an outcry,” she says.

Moses says both attempt to acknowledge a shared humanity regardless of race or gender.

“The phrase ‘I am a man’ and signifies dignity,” Moses says. “People think that I’m just the Black Lives Matter activist. But actually I’m a human rights advocate. And when I say ‘I am a man’ I am saying that I’m somebody, please treat me accordingly.”

She says black citizens are still trying to be treated with dignity.

“We’re not just being treated unfairly on the job,” Moses says. “We’re being treated unfairly in school. We’re being treated unfairly when we’re accused of something. We’re being treated unfairly when we’re considered for a job we’re being treated fairly when we walk down the street.”

What’s different today is that Memphis leaders acknowledge that the city was on the wrong side of history in 1968.

Memphis Mayor Jim Strickland says the city is prepared for the scrutiny that will come as the nation commemorates 50 years since King’s assassination here. It’s a better place, he says, but with work to be done.

“I love Memphis. I’m so optimistic about our future,” says Strickland. “But I don’t want to act like I’m ignorant of our challenges. Violent crime is way too high. Poverty is way too high and. Too few kids are getting properly educated.”

Last year the city maneuvered around state law to have Confederate statues removed from public parks. And it paid the 1968 sanitation workers a lump sum of $70,000 each because they’d never been eligible for a city pension.

“We have momentum to address the vestiges of racism and what racism has left us which is an unfair system,” Strickland says.

For 86-year old Elmore Nickelberry, the city payment has him planning for retirement.

“I’m hanging up my hat,” he says. “I’m going to California, put on them Bermuda shorts and running my feet through the sand.”

After 64 years of cleaning up the city, he’ll retire at the end of April.

(From NPR)