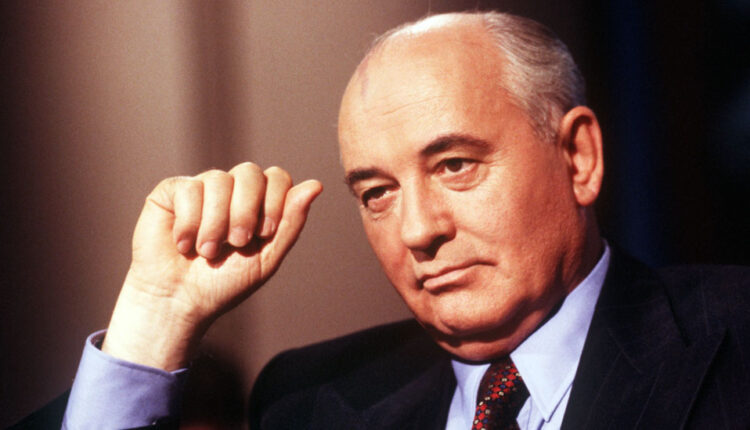

Mikhail Gorbachev, who presided over end of Cold War and Soviet empire, dead at 91

Mikhail Gorbachev, the former Soviet president whose gradual opening of his country paved the way for both the end of the Cold War and the collapse of the communist empire, died Tuesday at age 91.

Gorbachev died following a “serious and long illness,” officials at Moscow Central Clinical Hospital told Russian state media.

In a statement, United Nations Secretary-General António Guterres said he was “deeply saddened” to learn of Gorbachev’s passing, calling the former Soviet leader “a one-of-a kind statesman who changed the course of history.”

“He did more than any other individual to bring about the peaceful end of the Cold War,” Guterres added. “Receiving the 1990 Nobel Peace Prize, he observed that ‘peace is not unity in similarity but unity in diversity.’ He put this vital insight into practice by pursuing the path of negotiation, reform, transparency, and disarmament.”

Following the deaths of three Soviet leaders in just over two years, Gorbachev took control of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) in March 1985 amid a moribund national economy and heightened Cold War tensions with the United States, then led by the ardently imperialist Reagan administration.

In an attempt to address his country’s economic woes, Gorbachev implemented the policy of perestroika, or “restructuring,” which sought to improve efficiency by decentralizing decision-making. He also ushered in the age of glasnost, or “openness,” allowing for erstwhile unimaginable freedoms in what had for generations been a rigidly totalitarian state. Both of Gorbachev’s grandfathers were imprisoned in gulags during the Stalinist repression of his youth, and he and his family also survived the 1932-33 engineered famine that killed millions in Ukraine and other parts of the Soviet Union.

Despite then-President Ronald Reagan condemning the Soviet Union as an “evil empire” and U.S. nuclear aggression epitomized by the placement of new nuclear missiles in Europe and research into the so-called “Star Wars”space-based missile defense system, Gorbachev chose to pursue a policy of rapprochement with the United States. This led to a series of bilateral summits between the two leaders that bore fruits in the form of the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty signed in December 1987.

Gorbachev also presided over the pullout of Soviet forces from Afghanistan, a costly war lasting nearly a decade that ended the same way every invasion of Afghanistan over the past 200 years has ended—in defeated withdrawal.

More importantly, Gorbachev—unlike his predecessors—did not intervene militarily when Soviet satellite states in Eastern Europe began asserting their independence from Moscow, culminating in the dramatic destruction of the Berlin Wall in 1989 that effectively marked the end of the Cold War.

He later explained: “On the day I became Soviet leader, in March 1985, I had a special meeting with the leaders of the Warsaw Pact countries and told them, ‘You are independent, and we are independent. You are responsible for your policies, we are responsible for ours. We will not intervene in your affairs, I promise you.'”

In the end, the rot within the Soviet Union and the forces Gorbachev unleashed by opening its society proved too much and the once-mighty empire came crashing down in 1991. Many Russians blame Gorbachev for the loss of the power and prestige that came with being one of the world’s two superpowers, and some observers view Russian President Vladimir Putin’s aggressive policies and actions as an effort to regain lost Soviet glory—and territory.

By the time Gorbachev stepped down as the last Soviet leader on Christmas day 1991, relations with the West had been so thoroughly transformed that the USSR—which regularly used its veto power as a permanent member of the United Nations Security Council to thwart U.S. ambitions—voted in favor of the resolution authorizing the invasion of Saddam Hussein’s Iraq.

“We could only solve our problems by cooperating with other countries. It would have been paradoxical not to cooperate,” Gorbachev said of his policies. “And therefore we needed to put an end to the Iron Curtain, to change the nature of international relations, to rid them of ideological confrontation, and particularly to end the arms race.”

The U.S. has been accused of running roughshod over Gorbachev’s goodwill gestures during the post-Soviet era, especially by expanding NATO to Russia’s borders by admitting former Warsaw Pact members into the alliance.

Contrary to popular belief, Gorbachev said he never made any agreement with James Baker, Reagan’s secretary of state, to end the Cold War in exchange for a promise to not expand NATO.

“The topic of ‘NATO expansion’ was not discussed at all, and it wasn’t brought up in those years,” Gorbachev said in 2014. “Another issue we brought up was discussed: making sure that NATO’s military structures would not advance and that additional armed forces would not be deployed on the territory of the then-[East Germany] after German reunification.”

Last December, as Putin cited NATO provocation while preparing to invade Ukraine, Gorbachev accused the United States of growing “arrogant and self-confident” following the collapse of the Soviet Union.

“How can one count on equal relations with the United States and the West in such a position?” he asked.

“Americans have a severe disease—worse than AIDS,” Gorbachev said earlier. “It’s called the winner’s complex.”