Medicine: A powerful tool “to build a better world”

Identifying the most absurd among the countless measures taken by the U.S. against Cuba over six decades is nearly impossible.

These years of economic warfare, state terrorism, and ongoing hostility have resulted in countless human casualties and material losses within the Cuban population. The cruelty of this policy is well-documented, leaving no room for support for this sordid and multifaceted aggression on the island.

Nevertheless, there is a dimension of the damage that extends far beyond the archipelago’s borders. This includes imposing sanctions on Cuba and simultaneously targeting the leaders of countries that have sought and managed Cuban medical cooperation services.

Due to its cynicism, it is striking how one could oppose this support—an immense gesture of nobility and solidarity that has contributed to saving millions of lives across various countries worldwide.

This assistance has even been offered to the United States; for instance, after Hurricane Katrina devastated the Gulf Coast, the very same body of water someone has chosen to rename.

In light of such absurdities, it is worthwhile to remember some facts within context. For the patients treated with solidarity by Cuban Health, and for the rulers who facilitated that aid, perhaps nothing is more absurd than the decision to obstruct, cut off, or sabotage Cuba’s international medical collaboration programs.

If the extraterritorial nature of the sanctions imposed on Cuba by the United States is not enough, interrupting cooperation in the health sector is, by its very nature, perhaps the most extraterritorial, the most internationalized, and consequently, the most rejected by the peoples and governments that benefit from it.

One might wonder what the more than 2 billion patients, many of whom have been saved from death, would think if they were to learn of this American transgression.

How would they react if they were told that Cuban doctors are “slaves”? These same doctors, oftentimes in epic circumstances, alleviated their pain, saved their children or other relatives, assisted in the sublime moment of a child’s birth, and restored the sight of a few in a medical endeavor known as Operation Miracle.

The issue becomes even more significant when one realizes that these silent heroes have been present worldwide; inhabitants of around 160 countries can attest to what has been said here—throughout Latin America and the Caribbean, Africa, Asia, Oceania, and even developed parts of Europe.

No fewer than 400,000 aid workers have ventured forth with a backpack of solidarity to other nations, an unparalleled figure that not only demonstrates the human capital involved but also reflects a country’s commitment to a program with historical significance and continuity, showcasing colossal achievements over six decades.

There was always a Cuban doctor watching the sunrise in some corner, just as one of their compatriots was preparing to begin a night shift. It’s striking from any perspective.

Cuban aid workers were on the front lines when the devastating Ebola epidemic struck Africa; when around four million individuals suffering from cataracts and other ophthalmological ailments regained their sight, thanks to Operation Miracle.

Professional healthcare providers in white coats were among the first to arrive in distant Pakistan after a catastrophic earthquake; they have aided entire populations in the Amazon jungle, remote areas of Central America, and by the shores of beautiful Natadola Beach, a secluded spot in Fiji.

What of the Henry Reeve Contingent, which specializes in disaster situations and severe epidemics, named after the American-born soldier who died for Cuban independence? Viewed from another perspective, the name itself may represent an expression of the true American spirit, contributing to the irritation among the most extreme elements of the anti-Cuban faction in Miami/Washington.

This contingent, as is well-known, stood tall in no fewer than 56 countries where the COVID-19 pandemic caused many deaths due to inadequate medical attention.

Thus, they reached out to Italian, French, and Portuguese citizens, as well as British tourists aboard a cruise ship in the Caribbean, who were only welcomed into a Cuban port in Havana for their safety. This is the same city to which the U.S. Government mandates that its cruise ships cannot visit.

The measures against Cuban medical cooperation are equally absurd for hundreds of experts and officials from PAHO or WHO, who have deemed the island’s experience unique and unparalleled in the realm of international cooperation.

To support this notion, the Henry Reeve Contingent received the prestigious Dr. Lee Jong-wook Memorial Public Health Award from WHO in 2017.

Similarly, the World Peace Council formally nominated the Contingent for the Nobel Peace Prize in 2021.

The lack of support for the discrediting of Cuba’s medical cooperation worldwide remains clear, regardless of the pressure tactics employed.

Caribbean leaders’ firm stances, such as those of the Bahamas, St. Vincent and the Grenadines, Guyana, St. Lucia, and other regional allies, are fresh in their minds. The most recent example is Jamaica, whose Prime Minister refuted, with Marco Rubio standing next to him, the outrageous statement made by the Secretary of State, who labeled the international practice of Cuban medicine as atrocious.

It is likely that this absence of support does not concern U.S. leaders, but the millions of beneficiaries understand that this is indefensible from any perspective, regardless of religious belief or ideological stance.

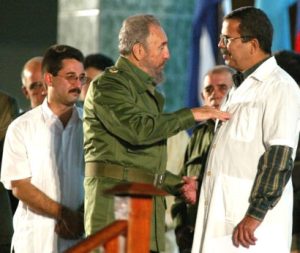

They surely concur with Fidel Castro Ruz when he asserted, “Medicine cannot be a business; it is a human right,” adding, “Medicine will be one of the most powerful tools to build a better world.”