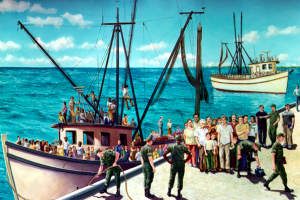

Mariel, 34 years ago

HAVANA — The port of Mariel, situated on a beautiful bay of the same name, on the northwestern coast of Cuba, has become news in recent days due to the major investments being made there to turn it into one of the most important container ports in the Caribbean.

But its international fame came long before, when, exactly 34 years ago, the bay was the epicenter of one of the most traumatic events in the history of Cuban immigration and its relations with the United States.

Much has been written about this event and it is impossible to describe it in a few words, so I’ll simply indicate what I consider to be its main characteristics and the lessons that resulted from it.

The emigration crisis at Mariel surprised both governments because neither party expected a migratory flow of that dimension.

At the time, the Cuban economy was going through one of the finest moments of the revolutionary period. Political stability was very high and the counter-revolution barely expressed itself inside the national territory.

Even the relations with the United States, though they showed some signs of deterioration, were going through their best period of distension, as a result of the policies of Jimmy Carter.

Although no kind of immigration accord existed between the two countries since Richard Nixon canceled the understanding adopted in 1965, and although the U.S. continued to encourage illegal departures from the island, the problem had remained at levels that were manageable for both parties.

Maybe for that reason, when on April 20, 1980, the government of Cuba decided to open the port of Mariel to anyone who wished to emigrate, Carter’s first response was that he would welcome those people “with open arms and hearts.”

In fact, the opposite occurred. The “Marielitos” ended up being considered by U.S. public opinion and official discourse as “the most despicable immigrants” ever to enter the country. In Cuba, they were considered as “scum” and harassed by “repudiation rallies” that created a humiliating situation for the victims and the people who hounded them.

In truth, because the Cuban government lifted all barriers and the U.S. was unable to select the newcomers, no other emigration flow in history represented Cuban society more than the emigration from Mariel.

Beginning with Mariel, Cuban emigration also changed drastically in social nature and politics, which explains the generalized incomprehension that its conduct originated.

The emigrants were no longer the most favored sectors of the old regime, the basic components of the so-called “historic exile,” but persons formed inside the revolutionary process, without basic contradictions with the Cuban regime, who emigrated for reasons created by the socialist process, in a preview of the characteristics that future emigrants would display.

The Marielitos experienced in the flesh the ignominies common to all illegal immigrants to the United States. Today, there are still many prejudices against them even in certain sectors of the Cuban-American community.

In Cuba, although initially the emigrants were forbidden to visit the homeland and later their visits were limited by quotas, they eventually were accepted like the rest. What’s maybe most surprising is that people here seldom talk about the event, an example of popular wisdom because their departure is the best that could have happened.

Despite the inconveniences they had to face, the Marielitos managed to integrate quite successfully into U.S. society. In Miami, according to the 2000 Census, 23 percent of the Marielitos held high-level professional jobs; 15 percent held jobs that required some degree of qualification, 15 percent worked on their own, and 22 percent held menial jobs.

As a result of that differentiation, it is estimated that 12 percent earned high wages but 20 percent lived below the poverty level.

Such indicators are less positive than those shown by those who arrived earlier and their descendants, but they are above those of recent immigrants, which shows their capacity to adjust to the process followed by the majority, where the time of permanence is determinant.

The Mariel boatlift also established the limits imposed by its own security to the U.S. policy of encouraging illegal emigration from Cuba.

The Mariel syndrome still terrifies U.S. society. Americans did not initially welcome the “rafters” to their territory in 1994, and the accords they adopted that year with Cuba provided for the repatriation of those intercepted on the high seas, dealing for the first time with the problem of control of illegal immigration.

The new Cuban immigration policy eliminates the domestic incentives for illegal emigration — at least there are no longer any official limitations that encourage it — and that corresponds with Washington’s interest in avoiding a new Mariel.

However, the interpretation of “dry foot-wet foot,” which accepts illegal Cuban migrants who evade the vigilance of the United States, has left loopholes that contradict U.S. legislation, increasing the danger for those who, rejected by the U.S. legal system, decide to embark on the adventure of entering U.S. territory illegally.

It is wise, then, to definitively solve this conundrum, because, if Mariel taught us anything, it is that nobody wins when chaos is fanned in a situation as sensitive as this one.

Progreso Semanal/ Weekly authorizes the total or partial reproduction of the articles by our journalists, so long as source and author are identified.