Inequality deepens

Suddenly, everyone seems to be talking about inequality. Barack Obama talks about it. Leading economists and other social scientists write about it. And no one talks about inequality more frequently or with more passion and persuasiveness than Pope Francis.

For years, the subject of inequality had been virtually taboo, especially in the United States. Even liberal Democratic politicians were loathe to acknowledge the reality of the obvious, even as the rich enclosed themselves in ever larger houses in gated communities while the rate of poverty rose and the wages of the average worker flat-lined or dropped. Democrats were also afraid because, while carrying on a vicious top-down class war of their own, the Republicans were able to score political points by accusing Democrats who brought up the subject of inequality of waging divisive class warfare. Moreover, Democrats were also fearful because much of their campaign cash came from the beneficiaries of rising inequality.

What has changed? There is a confluence of factors. The consequences of increasing inequality bite deeper and are more evident in the low-growth zombie economy that has become the new normal. The evidence about inequality from research continues to pile up and new studies continually show the connections between inequality and a multitude of other social ills. Then there is a new voice of moral authority emanating from the Vatican who not only talks the talk but also walks the walk, as when he fired a German bishop who spent a ton of church money on a house for himself.

Still, none of this is completely new. For some time, for instance, mounds of data and myriad rigorous studies have supported the conclusion that economic inequality has risen dramatically in recent decades. The social doctrine of the Catholic Church has not changed.

But something qualitatively different indeed is happening today. Economic inequality has not just been rising. It increasingly has become hereditary. The system of privilege and poverty is becoming petrified.

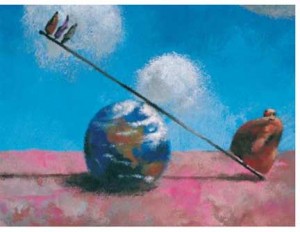

Modern apologists for inequality have always justified it by saying that a bigger pie benefits everyone and that equal opportunity makes the system fair by allowing for social mobility. But the pie is not growing now as it was before and any extra slices are swallowed up by the already economically obese making mobility a myth or at best, a memory.

Enter “patrimonial” or “oligarchic” capitalism. According to the eminent economist Paul Krugman, the best analysis of this latest twist in the inequality screw (pun intended) is contained in a new book, “Capital in the Twenty-First Century,” which Krugman describes as “the magnum opus of the French economist Thomas Piketty,” and predicts that it will be the most important economics book of the year — and maybe of the decade.”

Krugman goes on to add that “Mr. Piketty, arguably the world’s leading expert on income and wealth inequality does more than document the growing concentration of income in the hands of a small economic elite. He also makes a powerful case that we’re on the way back to “patrimonial capitalism,” in which the commanding heights of the economy are dominated not just by wealth, but also by inherited wealth, in which birth matters more than effort and talent.”

We are well along this road. Probably the most obvious (although scarcely the only) mechanism through which this process is taking place is the increasing cost of higher education. Education has always been touted, not without some reason, as the best way of moving up the economic ladder. Increasing costs obviously affect the rich least of all, at the same time knocking off a couple of rungs from the rickety social mobility ladder for the poor. But that’s not the end of the education/inequality story.

Things are getting worse, according to data from the Tuition Tracker Database, succinctly reported in The Miami Herald:

“Just about everybody knows that college has gotten more expensive, but a comprehensive new analysis reveals that those costs are rising faster for some — mainly the poorest families who already face huge hurdles to higher education.”

Decreasing federal and state assistance to college students and the institutions themselves deserve most of the blame. Thus, an even greater level of future economic inequality will be no accident: it is being engineered by government educational policy. To make matters worse, colleges and universities are giving a higher proportion of total assistance to children from richer families in order to attract students with higher test scores whose attendance increases the marketability of their institutions.

These trends belie yet another plank in the platform of inequality’s apologists. An even more important point is that the inequality deniers were working with a fallacy all along. One that enabled them to argue the system is fair in spite of massive inequality. Differences in educational achievement are important but are not the major cause of economic inequality.

The principal force is deeper and more systemic. As the publisher’s (Harvard University Press) synopsis of “Capital in the Twenty-First Century” states:

“Piketty shows that modern economic growth and the diffusion of knowledge have allowed us to avoid inequalities on the apocalyptic scale predicted by Karl Marx. But we have not modified the deep structures of capital and inequality as much as we thought in the optimistic decades following World War II. The main driver of inequality—the tendency of returns on capital to exceed the rate of economic growth—today threatens to generate extreme inequalities that stir discontent and undermine democratic values. But economic trends are not acts of God. Political action has curbed dangerous inequalities in the past, Piketty says, and may do so again.”

In simple terms, Piketty is saying that the tiny minority whose money works for them (capital’s owners, overwhelmingly the rich) are getting an ever larger share of the economy’s total output compared with the vast majority who work for their money (labor), whose cut of the pie is shrinking. There is no divine or scientific law that determines things have to be so. It is the result of the balance of political power and the policies that generates. This can be changed. It’s been done in the past. It could not happen too soon one more time.