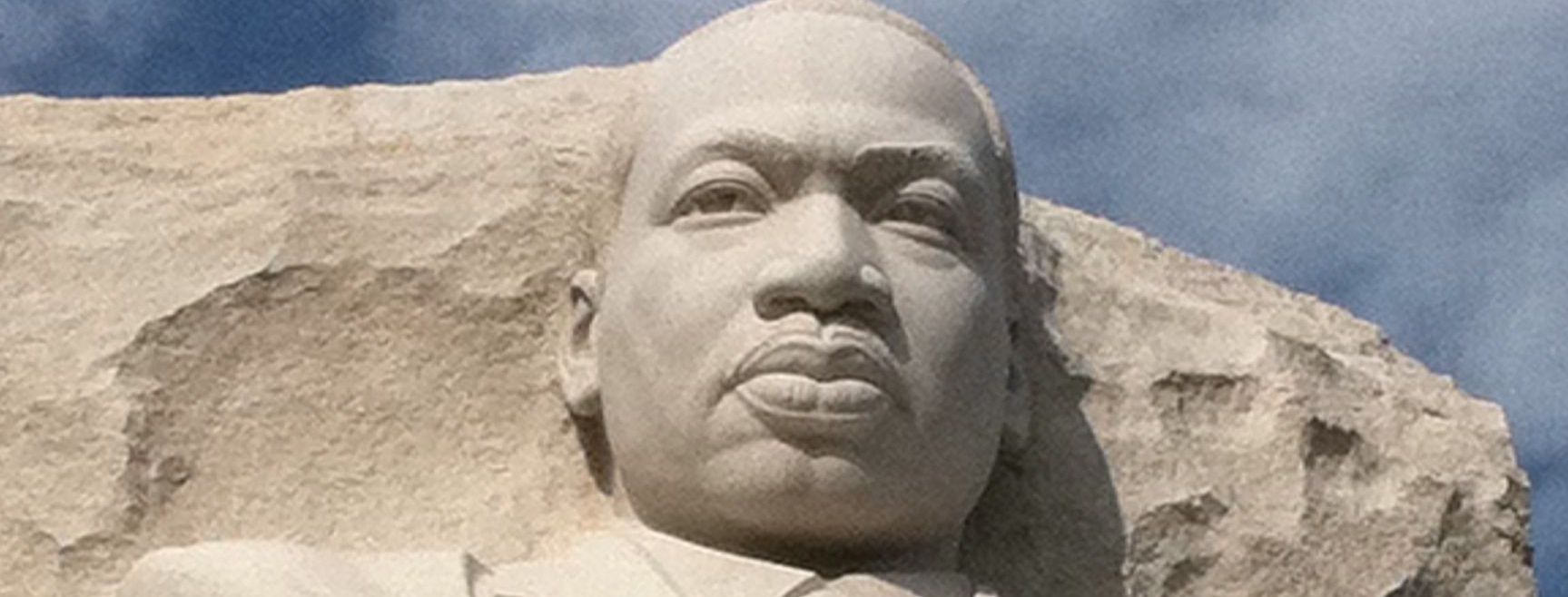

‘I have a dream’ remembered (+Video)

By Harry Belafonte

On 28 August 1963, Martin Luther King made his ‘I Have a Dream’ speech at the culmination of the March on Washington, giving the civil rights movement an unstoppable momentum. The singer, actor and social activist recalls an epoch-defining day.

The atmosphere that day in Washington was a mixture of hope and excitement. I think that everyone who attended the march felt empowered. There was a tremendous sense that we were pursuing a cause that was honorable, but, equally, that what we wanted was achievable. We were there as Americans and all of America was represented that day. It felt like we were witnessing a new moment, a renaissance of hope and activism. It was truly inspiring.

But, you know, it was not just the day, but the weeks and months and days leading up to it. As a civil rights activist, I had many conversations with Robert Kennedy, who was worried because he had listened too much to J. Edgar Hoover and the FBI, the rightwing voices of white America and the media who did not wish us well and were predicting great violence. We assured Robert Kennedy that it would be focused, well marshaled and non-violent and he wanted to believe us, but our detractors had his ear also. The city was surrounded by police and state troopers on the ready. So, we also had something to prove. And prove it we did.

It was glorious. We had high expectations and they were fulfilled. There was a young speaker I remember who preceded Dr. King, a forceful young man called John Lewis from the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, and he was very outspoken about America’s leaders even though he toned his rhetoric down after some of the civil rights people asked him to. That was a good speech. There were several rousing speeches before Dr. King took the platform, as well as music and singing. It was an energizing day.

Of course, the “I Have a Dream” speech was the event of the day. It has since been recognized as one of the great speeches of American history. I was not surprised by the content, because we had worked with him on it and we were in tune with the message, but what we were not prepared for was the delivery, the oratory. The imagery flowed, the language flowed. It was Shakespearean.

There is one thing I have to say about the speech, though, and I say it when I am called on to speak about Dr. King to students all over America. I tell them: you need to study the whole speech because the text before the “I Have a Dream” part is a deeper reflection of what he was striving for. The details and the passion of the struggle are spelt out in the preceding passages.

The spirit that Dr. King called forth was a profoundly American spirit, as was his struggle. What made me feel so good about that struggle was that it was ordinary people who were becoming empowered through his words, to realize their own possibilities.

Much of my political outlook was already in place when I encountered Dr. King. I was well on my way and utterly committed to the civil rights struggle. I came to him with expectations and he affirmed them. Like many black American men of my generation, I had lived through two defining moments: I had been born into the Great Depression and I had fought for America against the Nazis in the Second World War.

To then come back to an America where black people were denied their basic rights as citizens was to come back to a so-called democracy where political evils still taunted us. Then we looked around us and saw that England, Belgium, France, the great colonizers, were hanging on to their colonies even after the second world war. I believe to this day that it was that experience that underpinned the beginnings of the civil rights struggle in America. We had to take on the challenge, fight these injustices, these evils.

Dr. King’s legacy is a great one, but I have to say too that American schools have been shoddy in addressing it. It is simply not taught. Why? Because reactionary America is still trying to deny that hope and that achievement. Our legacy has been under severe attack by the rule makers, Congress, our courts and our judges, all of whom want to consign us to history and simultaneously undermine the struggles of today.

That is why I sometimes say in my speeches that we have to stop this deification of Dr King and look at him as an ordinary man who empowered himself and others through politics and activism. Look at the details of his struggle: the strategy, the speeches, the mind, the intellect. Then you can begin to understand how an ordinary man is empowered to find himself. Who was Martin Luther King before he was Dr. Martin Luther King? He came from somewhere and that somewhere was the same hardship and struggle to survive of many of his followers. He had the same fears and hopes and anxieties and aspirations. To deify him is, in a way, to reduce his achievement and to remove the radicalism from it. I would counsel against that and argue for a real reappraisal of his achievements, which were of the highest order.

One of my abiding memories of the day was something I will probably never experience again: such a tide of people leaving with such a sense of satisfaction and hope. That was America at its greatest. And I have no doubt we can get back there again by moving forward. We need leaders, though, spokesmen and women we can have faith in, not this compromised form of leadership that is cynical and speaks out for the power of the few at the cost of the many.

There is a new challenge now and a more complex one. Part of the dilemma is that, as Americans, we have talked ourselves into still believing in the nobility that America supposedly represents. But, the truth is that, right now, we are more villainous than we are righteous. For the moment, we cannot accept that. Black people are still bearing the brunt of that villainy, but today, the prism through which we must view the struggle is not just race, it is gender, it is economics, it is human rights, it is the growth of powerful elites and populist rightwing movements that seek to undermine American democracy while peddling their version of America the great.

But there is also a new passion for struggle on the horizon. People have once again had enough. Americans are opening their eyes to those in America who work tenaciously to keep America in this state of aggression and hostility and obsession with being number one. There is a cruelty about America and American politics and society that dumbfounds me. But there is also change in the air. In my experience, when people feel they have had enough, activism grows and, from activism, comes change.

I can feel it in the air when I speak at colleges all over America, which I am being asked to do now more than ever. Young people are hungry for change. They carry an optimism and a great sense of hope, but it has not yet been articulated. But, it will be because it must be. That, too, is Dr. King’s legacy. He made history, but history also made him.

(From the British newspaper The Guardian)