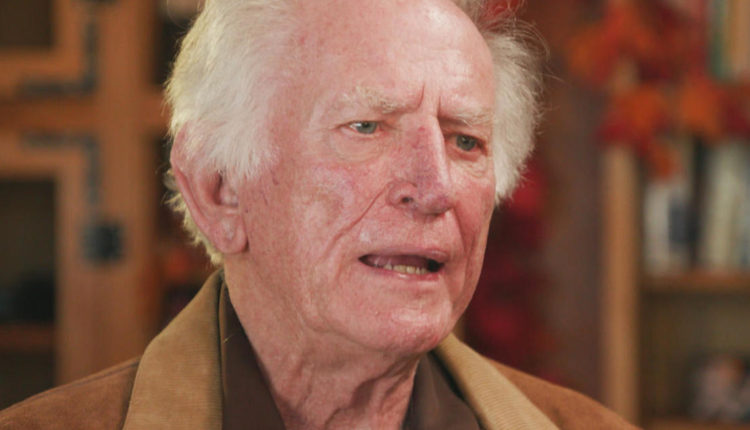

Gary Hart

Gary Hart

How powerful is the president?

Gary Hart / The New York Times

In 1975, after public revelations of intelligence abuses concealed from all but a handful of members of Congress, the United States Senate created a temporary committee to study the nation’s spy agencies — something no standing committee had ever attempted.

What came to be known as the Church Committee, after its chairman, Senator Frank Church of Idaho, recommended broad reforms, including the creation of a permanent Intelligence Oversight Committee. Former Vice President Walter Mondale and I are the last surviving members of the Church Committee.

We have recently come to learn of at least a hundred documents authorizing extraordinary presidential powers in the case of a national emergency, virtually dictatorial powers without congressional or judicial checks and balances. President Trump alluded to these authorities in March when he said, “I have the right to do a lot of things that people don’t even know about.” No matter who occupies the office, the American people have a right to know what extraordinary powers presidents believe they have. It is time for a new select committee to study these powers and their potential for abuse, and advise Congress on the ways in which it might, at a minimum, establish stringent oversight.

Secret powers began accumulating during the Eisenhower years and have grown by accretion ever since. The rationale originally was to permit a president to exercise necessary control in the case of nuclear war, an increasingly remote possibility since the Cold War’s end. An obscure provision in the Communications Act of 1934 empowers the president to suspend broadcast stations and other means of communication following a “proclamation by the President” of “national emergency.” Powers like these have been deployed sparingly: A few days after the Sept. 11 attacks, a proclamation declaring a national emergency, followed by an executive order days later, invoked some presidential powers, including the use of National Guard and U.S. military forces.

What little we know about these secret powers comes from the Brennan Center for Justice at the New York University Law School, but we believe they may include suspension of habeas corpus, surveillance, home intrusion, arrest without a judicial warrant, collective if not mass arrests and more; some could violate constitutional protections.

A number of us have urged immediate congressional investigations concerning what these powers are and why they have been kept secret. Public hearings should be held before the November elections, especially with rumors rife that the incumbent president might interfere with the election or refuse to accept the result if he felt in jeopardy of losing.

As the election approaches amid an expanding pandemic, it is highly doubtful that a full-scale public investigation of these powers will be conducted before November. But there is time for Congress to organize a select committee for the purpose of investigating and disclosing these secret presidential powers.

Among the questions to be addressed: Where did these secret powers come from? Where are they kept? Who has access to them? What qualifies as a national emergency sufficient to suspend virtually all constitutional protection? And critically, why must these powers be secret?

This proposed select committee could then resume proceedings after the election to examine whether such an extra-constitutional system is justified.

The Church Committee offers a template. Senior members of both parties should convene hearings by first requesting, or if necessary, subpoenaing, the documents themselves. Those from previous administrations familiar with these documents should be called to testify, as well as current officials, including the national security adviser, the attorney general and the White House counsel.

The most obvious first question is why these far-reaching powers are kept secret, not only from Congress but also from the American people. The second question is why they are necessary at all. And ultimately, should not there be permanent congressional oversight of any suggestion for calling these powers into operation? Under what dire conditions should our system of checks and balances among the executive, legislative and judicial branches be abandoned in favor of a dictatorship? And once a dictatorship is declared, what would be required to return us to our historic democratic system of government?

Clearly, in either house of Congress, a standing committee could be authorized to conduct these hearings and investigations. But a select committee signals special attention, singular focus and a dedicated mission not distracted by other duties.

We are not living in ordinary political times. Great temptations are offered to a president faced with defeat to declare a national emergency, for dangers at home or abroad capable of manufacture, and thus have unchecked access to dozens of extreme powers unknown to our founders or our Constitution.

Some dismiss such concerns as improbable. But much that has transpired in the past three and a half years has seemed improbable, until it happened. Why doubt the intentions of a president who said in the White House briefing room in April, “when somebody is the president of the United States, the authority is total, and that’s the way it’s got to be”?

Surely, regardless of party or candidate preference, we can all agree there is no justification for a president to have dictatorial powers kept secret from Congress, the press and the American people.

Gary Hart is a former Democratic senator from Colorado and a former presidential candidate.