Google Ideas is not Google

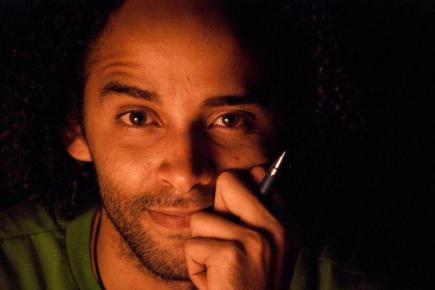

In order to approach from different directions the possible implications of the visits to Cuba of some Google executives in the past several weeks, Progreso Weekly interviewed engineer Karel Pérez Alejo, a Cuban web developer and university professor.

Q.: Recently there have been comments in some Cuba circles about the visit to Cuba made — for the second time in less than a year — by some managers of Google. What can you tell us, from your experience, about the reasons for this approximation to Cuba by Google and what could its impact be?

A.: It might be useful to recapitulate a bit. Google began as a small enterprise in Silicon Valley, emerging from the academic world of Silicon Valley, where two young men who were doing post-doctoral studies decided to create a search drive at a time when none of the existing searchers provided adequate service.

They developed an algorithm that today is one of the basic algorithms for search and information recovery, called the Page Rank, and starting from there they tried to capitalize a business. First they started with risk capital and the donations from investors at the time of the dot-com bubble, while they still didn’t have a defined product.

They reached a higher plateau, where they integrated an advertising product that worked on two tracks: Google Adwords, which offers advertisers a platform to place their results in the searchers, and Google Adsense, where they proposed to website owners a plataform for moneymaking, where they could show advertisements.

Starting there, they began to capitalize the search engine. Each search made by any Google user is a search that generates income, because it shows advertisements for which someone is paying. They managed, for the first time and very effectively, to fix a value on (or monetize) the searches for information. That’s the basic stuff.

During Google’s developmental stage, the investors asked for a chief executive officer who might have experience in Silicon Valley.

After studying several options — in which Steve Jobs was surely involved — they leaned toward Eric Schmidt, who took that enterprise (which faced strong competition in Yahoo!, Altavista and other searchers) to the level of a top global business.

Google then reached the point where it was one of the companies with the greatest power and greatest information reach. Since then, it has greatly diversified its products.

It also reached the point where it created a professional culture where many of the computer specialists, in the U.S. and the world, saw Google as one of the best places in which to work.

But it hadn’t diversified its means of income. On this issue, it was relatively fragile, because almost 89 percent of its revenue was obtained solely from advertisements.

If most of your income comes from a single product, you’re susceptible to being elbowed out by another technology — what’s called a “killer application” — that displaces the way in which you’re placing the ad on the Internet. That is why you have the portables, the Androids, competing directly against the iPhones.

That is why the Google folks began to develop other projects that involved not only universities but also the U.S. military-industrial machine. One of the most important projects was the development of self-operating vehicles, which has a great military application because it’s the land version of a drone. They also developed a robot-related device.

Also, Google collects a huge amount of information about its users. Every time someone enters Google and types a question, it’s telling Google what he’s interested in, what he doesn’t know, what is his need for information, etc. At some point, that need for information can be used by Google in its own products.

That, basically, is Google’s evolution.

Some three or four years ago, Schmidt turns his CEO post over to Larry Page, one of the two young men who founded Google. This is an acknowledgment of the maturity reached by the two creators/founders and leaves Schmidt free to do other things.

Now then, who is Eric Schmidt? Julian Assange answers that question in an interview with Amy Goodman.

In addition to being a brilliant entrepreneur, he has close personal links to the U.S. State Department, especially to Hillary Clinton.

In addition to being a brilliant entrepreneur, he has close personal links to the U.S. State Department, especially to Hillary Clinton.

Another character joins the company: Jared Cohen, who had been a member of Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice’s work team, and kept the job under Hillary Clinton. He reached his zenith when he helped develop “21st-Century statecraft,” or how to practice diplomacy with 21st-Century technology.

According with his public profile, Cohen is a specialist in “digital terrorism,” “the promotion of freedom of expression [and the] use of technology by civil society.” He has had experience in the Balkans and the Middle East in the promotion of the use of technology in the overthrow of governments or regime change in countries “in crisis.”

For some reason, which may be Clinton’s departure from the State Department, Schmidt hires Cohen, sets up a “little project” for him, gives him a building in New York City and the funds needed so he can continue to do the job he was doing at the State Department.

A research branch is created. They say it goes beyond a branch because they don’t define themselves as a think tank but as a think/doer, in other words, they not only think but also act. That turned into Google Ideas.

In its official website, Google Ideas describes its main projects. One of them is to provide free lodging to websites under the protection of the entire Google platform, making them invulnerable to any government that tries to take down the site.

Other projects are providing the Internet to hard-to-reach regions by using balloons and one that enables users to draft online their own proposals for a Constitution. Those two are unacceptable to Cuba.

Q.: How important was for Google to come to Cuba?

A.: My opinion is that Google didn’t come. Google Ideas came, and came twice. Google Ideas is very close to the State Department, especially to Hillary Clinton, who will likely run for the presidency on the Democratic ticket.

Why do I make a distinction between Google and Google Ideas? Because in those two visits to Cuba nobody came with a technological focus and — from what I’ve heard about talks — nobody talked about technology but about technological politics.

What does Google offer Cuba? They made a gesture after the first visit consisting of opening a navigator [Google Chrome] free of charge. Being a free service, Chrome does not entail a commercial relationship with the Cuban government so it doesn’t fall under the restrictions of the Treasury Department. But neither does Mozilla, Apple or Microsoft, so it’s a limitation that makes no sense.

There’s something interesting about Google’s limitations in Cuba. Until 2007, maybe 2009, one of Google’s two packages of advertising, Google Adsense, was closed to Cuba, but Google Adwords (for which you paid Google for your advertisements) was open.

It could be said that, until 2009 when they shut down access to Google Adwords, they were ignoring the prohibitions imposed by the OFAC [Office of Foreign Assets Control] regarding Cuba by allowing us here to use their “star service.” Therefore, they were ambivalent with regard to what they open to Cuba and what they keep closed.

Another example is Google Analytics, which they closed to us. They have reopened it but we noticed that they didn’t open it fully or that they don’t realize that they have to open it fully, because — although you can access the service — you cannot download the report from Cuba. You have to enter through a proxy.

In other words, there has been some carelessness in the criteria they’ve been using regarding access to Google services from Cuba.

But that’s not Google Ideas, whose projects are essentially directed at subversion — through the use of technology — in countries with freedom-of-expression problems, as they understand them.

From the point of view of a percentage of the State Department officials and some of the Google executives, Cuba could be the ideal location to apply Google Ideas products. “Publish your site with me, so the Cuban government can’t close it; navigate through this protected network without problems; write a proposal for a new Constitution for Cuba.”

What these visits are doing resembles an on-site study.

Is there anything new, with a strong impact, that Google can offer us? Well, the search engine — its most important product — is open. The G-mail service is open. Most of the analytical tools used by web developers are open. Electronic commerce is closed, but we can’t engage in electronic commerce anyway.

In practice, Google has little to offer us that could change our digital surroundings and the computerization of Cuban society.

In my opinion, before approaching them, we should look at similar products developed by Cuba’s strategic allies in the field of telecommunications — Russia and China.

For example, if we planned to build a Cuban searcher and needed a transfer of technology we wouldn’t need to approach Google directly, because everyone knows that its intentions are not crystal clear.

It would be better to turn to either Russia or China, which have strong technological development. I see nothing that Google can offer, nothing that might impact drastically on us.

Q.: Might someone think that you’re being a bit paranoid about Google?

A.: Look, I’m a web developer and install Google Analytics in all the sites I’ve developed. I know that I’m giving information to Google, but they have it anyway, through their analysis of Cuba’s traffic.

Still, it’s a free tool that helps us a lot in terms of the capacity and structure that would have to be generated in Cuba to perform the same volume of analysis. And I favor installing it just for that reason.

But we shouldn’t be naïve, particularly with regard to the visit of the Google Ideas people. It would have been very different if executives from Google Glass or Google Map had come instead. But it wasn’t Google’s technical wing that came; it was the political wing, which is an extension of the U.S. State Department.

I would feel the same if it were Yahoo Ideas, because they’re not interested in technical issues. I tell you again: we cannot be naïve about this.