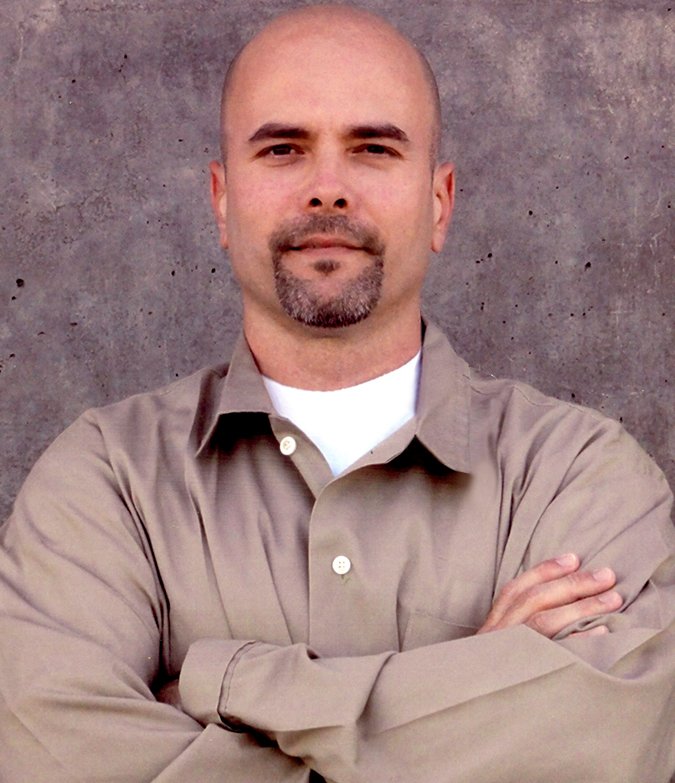

Gerardo Hernández: guilty as charged? Alan Gross: innocent as claimed?

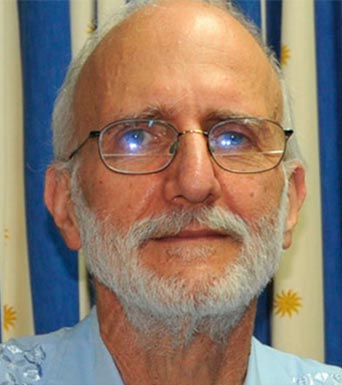

It should be easier to make a deal. A 65-year-old American USAID subcontractor named Alan Gross is serving 15 years in a Cuban prison for smuggling sophisticated telecommunications equipment into Cuba. Cuban officials say they’re prepared to discuss his fate without pre-conditions as a “humanitarian” gesture. But it is also clear they want to exchange him for the three members of their Cuban Five intelligence network still in prison in the United States.

There are precedents for such a swap. In 2010, Washington acted quickly to trade 10 Russian deep-cover spies for four men the Russian government had imprisoned for “illegal contacts” with the West. There is also the example of Israel. In 2011, Israel freed more than 1,000 Palestinian prisoners to win the release of Gilad Shalit, an Israeli soldier captured by Hamas five years earlier. And yet — even after a November 2013 letter signed by a bipartisan group of 66 Senators urging President Obama to “act expeditiously to take whatever steps are in the national interest to obtain [Gross’s] release,” — the U.S. Administration refuses to negotiate. Why? Three words: Castro, Cuba, murder. Even for those who can get past the first two, the third is often, understandably, a show-stopper. In 2001, Gerardo Hernández, the leader of the Cuban Five, was charged and convicted of “conspiracy to commit murder” in connection with a 1996 shootdown of two civilian aircraft over the Florida Straits that resulted in the deaths of four men. He was sentenced to two life terms plus 15 years in prison. How can the United States exchange a man convicted of conspiracy to commit murder for someone the State Department continues to insist did nothing wrong? It’s worth unpacking both sides of that conventional wisdom. Let’s start with the case of Gerardo Hernández.

The shootdown

On February 24, 1996, Cuban Air Force MiGs shot down two Brothers to the Rescue planes, killing the four civilians aboard.

The shootdown triggered not only an international incident between the two countries but also an outpouring of rage and demands for revenge from Miami’s Cuban-American exile community.

We can argue today whether the planes were in Cuban or international airspace when they were shot down. Or debate whether the shootdown was a reasonable response to Brothers’ provocation. But none of those legitimate debates has anything to do with the central issue: What role, if any, did Gerardo Hernández play in the shootdown of the planes? Could he have known in advance the Cuban military was planning to shoot down the aircraft? Would he have had any control over, influence on, or role in the Cuban military’s plan to bring down the planes?

During much of the time leading up to the shootdown (from October 1995 to January 26, 1996), Gerardo Hernández was on vacation in Cuba. Another agent, identified in trial documents as Manny Ruiz, took his place and remained in Miami until at least mid-March 1996. Ruiz, a major and Hernández’s superior in the Cuban intelligence command structure, controlled the decoding program required to communicate directly with their bosses in Havana until after March 14, 1996 — 17 days after the shootdown. On January 29, 1996, Havana sent a high frequency message to Ruiz: “Superior headquarters,” it said, “approved Operation Scorpion in order to perfect the confrontation of counter-revolutionary actions of Brothers to the Rescue.” The message said Havana needed to know “without a doubt” when Brothers leader José Basulto was flying and “whether or not activity of dropping of leaflets or violation of air space.” Although prosecutors would later claim these documents showed Hernández played a role in Operation Scorpion — the basis of the conspiracy to commit murder charge — the documents clearly show this message was addressed to Ruiz, not Hernández. Two weeks later, on February 12, a second message concerning Operation Scorpion was sent to field agent René González and signed using the code names for both Ruiz and Hernández. Hernández says he “did not write or send the message of February 12.” There are a number of reasons to believe him. For starters, the message adopts almost precisely the same wording as the January 29 message, including repeating two errors Ruiz might not have caught but Hernández surely would. The message cryptically instructed González to “find excuse not to fly” on future Brothers missions. The reality was that González had stopped flying with Brothers more than two years earlier. Hernández would have known that. The message also referred to González as Iselin, one of his two code names, but one which Hernández did not use in any of his other messages to him. And what did “perfect the confrontation” mean? Judge Phyllis A. Kravitch — in her 2008 dissent from a decision of the 11th Circuit of the U.S. Court of Appeals — pointed out: “There are many ways a country could ‘confront’ foreign aircraft. Forced landings, warning shots, and forced escorted journeys out of a country’s territorial airspace are among them — as are shoot downs.” Would Cuban State Security have told Hernández in advance it planned to shoot down the planes? That’s highly unlikely. Cuban intelligence is incredibly compartmentalized; information is shared on a need-to-know basis only. Hernández, a mid-level field intelligence agent, would have had no need to know. During this time, Hernández did have other important mission responsibilities. He was in charge of Operation Venecia, an unrelated plan to help another agent inside Brothers, Juan Pablo Roque, to re-defect back to Cuba. Operation Venecia was successful — Roque flew out of Miami on February 23, 1996. On March 1, the Cuban Intelligence Directorate sent a message of congratulation to its agents in Miami: “Everything turned out well,” it said. “The commander in chief visited [Roque] twice, being able to exchange the details of the operation. We have dealt the Miami right a hard blow, in which your role has been decisive.” The message did not refer to either Operation Scorpion or Operation Venecia. Instead it offered “our profound recognition” for Operation German. Based on the context of the message and the fact that Roque’s code name was “German,” it seems clear this message refers to Roque’s defection. During the trial, however, prosecutors argued the message congratulated Hernández for his role in the shootdown. Prosecutors also claimed Hernández’s promotion to Captain in Cuba’s Ministry of the Interior on June 6, 1996, represented another acknowledgment of his key role in the shootdown. But June 6 is the anniversary of the founding of Cuba’s Ministry of the Interior, the date on which routine long-service promotions are granted to qualifying MININT employees. Having completed four years as lieutenant, Hernández had automatically been promoted. As Judge Kravitch concluded in her appeal dissent, prosecutors “presented no evidence” to link Hernández to the shootdown. “I cannot say that a reasonable jury — given all the evidence — could conclude beyond a reasonable doubt that Hernández agreed to a shoot down.”

The charge

Which brings us to the issue of why prosecutors decided to charge Hernández with conspiracy to commit murder. It was not one of the original charges laid after the Cuban agents were arrested on September 12, 1998. Prosecutors only added it seven months later, on May 7, 1999.

Why the delay?

FBI agents had penetrated the Cuban network as early as December of 1996, and decrypted and translated the relevant messages well before the arrests. There are several possible explanations for the decision to escalate the case by tacking on the murder charge.

– Although prosecutors in 1998 boasted the FBI broke a “very sophisticated” spy ring, journalists and commentators quickly focused on just how unsophisticated the operation seemed. Critics had begun to dismiss the case as “second-rate.” That changed, of course, as soon as the murder charge was added.

– The FBI was under fire from exile leaders in Miami for failing to charge anyone in connection with the shootdown. Soon after the 1998 arrests, Congressman Lincoln Díaz-Balart called on the Clinton administration to charge the arrested agents “for the murder of four members of Brothers to the Rescue” — even though no evidence then connected them to the incident.

The trial

The conspiracy to commit murder charge became the central focus of the seven-month trial.

Did the prosecution present a compelling case?

They didn’t believe so. At the conclusion of the trial, they filed a last-minute emergency petition attacking the judge’s instructions to the jury and demanding she be prohibited from presenting them to the jury. During those instructions, Judge Joan Lenard had outlined the level of proof required to convict Hernández of conspiracy to murder. In a petition to the 11th Circuit Court of Appeal on May 25, 2001, the prosecutors threw up their hands. “In light of the evidence presented in this trial,” the petition declared, the judge’s instruction “presents an insurmountable hurdle for the United States in this case, and will likely result in the failure of the prosecution.” What the prosecutors were saying, quite simply, is that if the jury followed the judge’s instruction, they would have little choice but to acquit Hernández. If they followed the judge’s instruction… The Appeal Court rejected the prosecutors’ petition, but the jury convicted the Five on every single count, including conspiracy to murder.

The jury

Which brings us to the jury, and the political climate in Miami at the time of the trial.

There is a traditional hostility among Miami’s exile community to anyone associated with the Castro government. But the climate was even more toxic in the lead-up to the trial:

– Elian González, a Cuban boy, had washed up on Florida’s shores in November 1999. After an emotional and legal tug of war between his father in Cuba and his extended family in Miami, he was returned to his family in Cuba, ratcheting up the anger toward Cuba among many in Miami.

– Although much of the Miami media would have been reflexively anti-Cuban in the best of circumstances, we now know some virulently anti-Cuban journalists and commentators, including some who wrote about the case before and during the trial, were secretly paid thousands of dollars by the U.S. Government through the Board of Broadcast Governors.

– There was still anger and frustration among many in Miami because no one had been charged for the shootdown of the planes two years before, with some officials suggesting indicting Fidel Castro; Gerardo Hernández, it is fair to suggest, became the best available substitute.

Before and during the trial, the defence applied for a change of venue because of the climate of hostility in Miami. Those requests were all turned down. In the years since their convictions, however, a number of respected international organizations have raised questions about whether the accused got a fair trial. Amnesty International, in a 2010 report concluded: “A central, underlying concern relates to the fairness of holding the trial in Miami, given the pervasive community hostility toward the Cuban government in the area and media and other events which took place before and during the trial. There is evidence to suggest that these factors made it impossible to ensure a wholly impartial jury.” Added the United Nations Working Group on Arbitrary Detention in a 2005 report: “The climate of bias and prejudice against the accused in Miami persisted and helped to present the accused as guilty from the beginning. ” Amnesty International also questioned “the strength of the evidence on which Gerardo Hernández was convicted of conspiracy to murder… [Amnesty] believes that there are questions as to whether the government discharged its burden of proof that Hernández planned a shoot-down of BTTR planes in international airspace, and thus within US jurisdiction, which was a necessary element of the charge against him.” To repeat, once again, the opinion of Judge Kravitch, prosecutors “presented no evidence” to link Hernández to the shootdown. “I cannot say that a reasonable jury — given all the evidence — could conclude beyond a reasonable doubt that Hernández agreed to a shoot down.”

The case of Alan Gross

If it’s obvious the case against Gerardo Hernández is not as clear cut as the State Department would have us believe, neither is the case for Alan Gross.

On December 3, 2009, Cuban authorities arrested Gross and later charged him with “acts against the independence and territorial integrity of the state.” He was convicted and sentenced to 15 years in prison. Although the State Department continues to describe him as a humanitarian do-gooder attempting to help Cuba’s small Jewish community connect to the Internet, the facts are more complex. Cuba’s 1,500-member Jewish community has generally good relations with the island’s government. And they already had Internet connections. As the Jewish Telegraphic Agency, a global Jewish news service, would report later: “the main Jewish groups in Cuba denied having any contracts with Alan Gross or any knowledge of his project.” In 2008, Gross had signed a one-year deal with Development Associates International, a USAID-connected firm, to import communications equipment into Cuba, set up three WiFi hot spots — one each in Havana, Camaguey and Santiago — and train Cubans to use them. He was paid $258,264. That equipment included BGANS (Broadband Global Network Systems, which function as a satellite phone bypassing the local phone system and can also provide Internet signals and be used to establish its own WiFi hotspot, allowing it to operate undetected by government servers) and at least one specialized sophisticated SIM card, capable of preventing satellite phone transmissions from being detected within 400 kilometres. Such SIM cards are not available for general sale in the U.S. and are most frequently used by the CIA and the Defense Department.Despite U.S. travel restrictions, Gross made five visits to Cuba in 2009 alone. He never informed Cuba of his mission, and invariably flew into the country on a tourist visa. To smuggle his equipment into the country without arousing suspicion, Gross sometimes used unsuspecting members of religious groups as “mules.” In December 2009, Gross had been scheduled to deliver a BGANS device to a Havana university professor who’d been using a similar U.S.-supplied device to send information on “the Cuban situation” to his handlers in the United States. He was actually a double agent working for Cuban State Security. Gross was arrested. When Cuban authorities arrested Gross, they uncovered a treasure trove of reports back to his bosses in Washington in which he acknowledged the dangerous nature of the work he was doing. “This is very risky business in no uncertain terms,” he wrote at one point, adding that “detection of satellite signals would be catastrophic.”

Conclusion

So if Alan Gross is not quite as innocent as claimed, and Gerardo Hernández is not as guilty as judged, where does that leave us?

The truth is that — whatever their violations of the laws of the countries in which the two men were arrested — both Alan Gross and Gerardo Hernández are two more human victims of more than 50 years of failed American policy toward Cuba. Their continued incarcerations represent — for both sides — a major impediment to improving relations between the two countries. The Cuban government has expressed a willingness to discuss Alan Gross’s fate without pre-conditions. It is past time for the United States, which is ultimately responsible for Alan Gross’s failed mission in Cuba, to do the same.

Correction: In the original version of this post, it stated that the purpose of the prosecutors’ emergency petition on May 25, 2001, was “to prevent the jurors from voting on the murder count.” In fact, the purpose was to prevent the jurors from hearing certain aspects of the judge’s instructions because prosecutors believed if the jurors followed the judge’s instruction, they would likely vote to acquit the defendant. The error has been corrected in this version. (June 8, 2014)

(By: Stephen Kimber)