Why did Evo win?

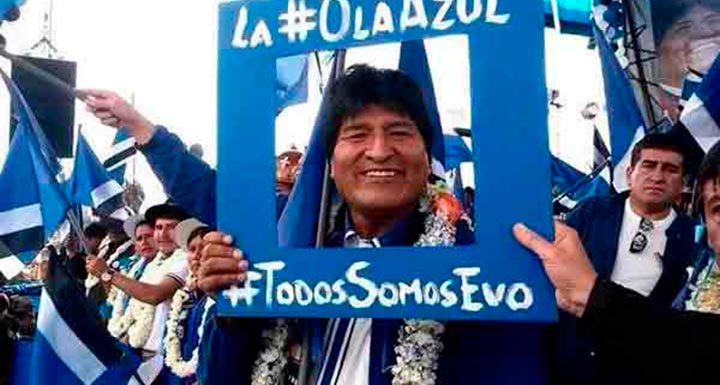

The landslide victory of Evo Morales has a very simple explanation: he won because his government has been, without a doubt, the best in the troubled history of Bolivia. “The best” means, of course, that he came through on the great promise, so many times unfulfilled, of all democracies: to guarantee the material and spiritual well being of the large national majorities, from that heterogeneous mass of oppressed plebeians, exploited and humiliated for centuries. It is no exaggeration whatsoever to say that Evo represents a watershed moment for Bolivian history: there is a Bolivia before his government and one after, a distinct and better one that came after his arrival to thePalacio Quemado.

This new Bolivia, crystallized in the Plurinational State, has definitively buried the other one: colonial, racist, elitist, that nothing nor anyone will be able to resuscitate. A frequently made error is to attribute this real historic feat to some good economic luck that has supposedly spread all over Bolivia thanks to the tailwinds of the global economy, ignoring that not long after Evo’s arrival, the global economy went into a recession, which it still has not overcome. Without a doubt, his government has smartly managed the economy, but in our opinion what explains his extraordinary leadership is the fact that with Evo a true political and social revolution has been unleashed, whose most outstanding symbol is the establishment, for the first time in Bolivian history, a government comprised of social movements.

MAS [Movement Toward Socialism] is not a party in the strict sense of the term, instead it is a grand coalition of the popular organizations of a diverse type that grew until it was able to incorporate into its hegemony the “middle class” sectors, who in the past had been fervently opposed to the cocalero leader. That is why it is no surprise that in the Bolivian revolutionary process (remember that a revolution is always a process, never a single act) numerous contradictions have emerged that Alvaro Garcia Linera, Evo’s running mate, interprets as creative tensions that emerge in every revolution. No revolution is free of contradictions, just like every living thing; but what distinguishes Evo’s administration is the fact that it went about solving them correctly, strengthening the popular bloc and reaffirming its dominance in the realm of the State.

A president who when he made a mistake — for example the massive increase in gasoline prices in December of 2010 — admitted his error and after hearing the voices of the popular organizations, annulled the increase in prices that was decreed a few days before. This infrequent sensibility of being able to hear the voice of the people and respond accordingly explains why Evo has achieved what Lula and Dilma were not able to: transform their electoral majority into political hegemony, which is the capacity to forge a new historic bloc and create ever larger alliances, but ones that are always under the direction of the organized people within social movements.

Obviously everything described above would not have been able to rely solely political ability of Evo or in the fascination with a story that exalts the epic of Indigenous peoples. Without an adequate root in the material lives of people, all of that would have vanished without leaving any traces. But that was combined with significant economic achievements that gave him the necessary conditions to construct the political hegemony that made his overwhelming victory possible. GDP went from USD $9,525,000,000 in 2005 to USD $30,381,000,000 in 2013, and GDP per capita jumped from USD $1,010 to USD $2,757 during the same period. The key to that growth — and that distribution! — can be found in the nationalization of the hydrocarbon sector, something without precedent in Bolivian history.

In the past the distribution of gas and oil profits left 82 percent in the hands of the transnational corporations, while the State only received the remaining 18 percent, with Evo those figures were inverted and now the lion’s share stays in the hands of the treasury. It is therefore unsurprising that a country used to suffer from chronic deficits in its fiscal accounts finished 2013 with USD $14,430,000,000 in international reserves (versus the USD $1,714,000,000 it had in 2005). To understand the significance of this figure, suffice it to say that it represents 47 percent of GDP, by far the highest percentage in Latin America. In line with the aforementioned, extreme poverty dropped from 39 percent in 2005 to 18 percent in 2013 and the goal is to eradicate it completely by 2025.

With Sunday’s result Evo will remain in the Palacio Quemado until 2020, a moment where his refoundational project will reach the point of no return. It is still undetermined if he will keep a two thirds majority in the Congress, which would make possible the approval of a constitutional reform that would open up the possibility of indefinite re-election. Given this there will no doubt be those up in arms accusing the Bolivian president of being a dictator or of hoping to remain in power. These would be hypocritical and fake democratic voices that never expressed the same concern for the 16 year rule of Helmut Kohl in Germany or 14 year rule of the lobbyist for Spanish transnational corporations, Felipe Gonzalez. What in Europe is considered a virtue, unquestionable proof of predictability or political stability, in the case of Bolivia it becomes an intolerable vice that reveals the supposed despotic essence of the MAS project. This is nothing new: there are morals for Europeans and distinct ones for Indians. Simple as that.

(From the: Telesur)