Entrepreneurship, between aspiring and being

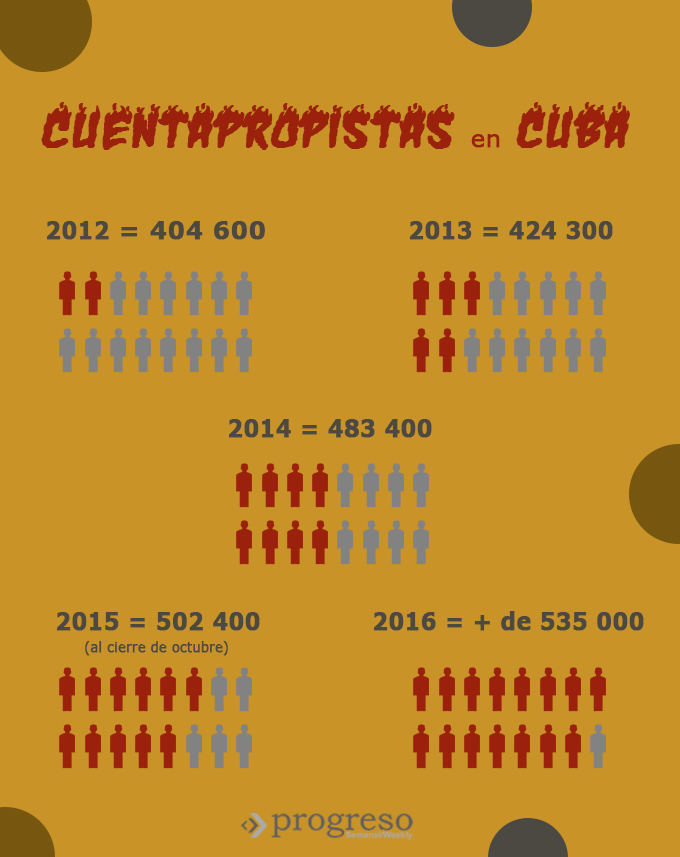

HAVANA — On Oct. 13, 2010, self-employed entrepreneurship resurged in Cuba. For the first time ever, the nation’s top leaders advocated its expansion with wide-ranging measures. However, the resurgence was different because of restrictions to the original concept.

According to experts on the subject, beyond the concept there’s the question of creating opportunities and truly fostering its development. It so happens that the term, “cuentapropismo,” is too narrow for some people, not only because of what they do but also because of what they’d like to be.

[Translator’s Note: The word is a conflation of “por cuenta propia,” meaning working “for oneself.”]

Some people dream of exporting their products or services but that’s an expectation far beyond the authorized restrictions, with an additional limitation: self-employment does not have a legal personality.

According to economist Ricardo Torres (1), a characteristic of the approved economic figures, related to their sectorial profile, is their location among non-trade activities, i.e., activities without the possibility of importation or exportation. This is a problem in itself, due to the country’s need to substantially increase the volume of sales abroad.

The reasons, Torres explains, respond to a combination of regulations: the maintenance and even deepening of the state monopoly on foreign trade; a monetary and exchange system that hinders access to foreign currency for operations of foreign trade, and the expansion to sectors that are basically directed to the domestic market.

While data from Latin America point to a low participation of this sector in exports (about 10 percent), the truth is that — by definition — its role in Cuba is and will continue to be very low if the present trend persists, the researcher says.

Economist Omar Everleny Pérez Villanueva reasons that, while the list of 201 permissible activities played its initial role, at present it would be more viable to establish a negative list, that is, those activities that the State does not wish private entrepreneurs to perform, such as Education and Medicine.

Following that logic, we might see the emergence of figures such as exporter, tour operator, travel agent, and even offices of engineers, lawyers, architects and economists in the form of small and medium enterprises (PYMES), Pérez says.

Pérez argues that one of Cuba’s most precious assets is the expertise of its human resources, a talent not fully utilized.

“It would be possible to prevent the drift of people with a high degree of education toward jobs with a low added value but higher wages,” he says, “and even to slow down their emigration overseas.”

In many cases, the State should legalize and tax activities that today exist in the informal sector, he says. That way, the State could add to its budget, which has suffered an increasing deficit in recent years.

Nevertheless, there is a greater challenge that shakes the foundations of Cuba’s traditional economic model. It consists of recognizing the existence of the private sector, regulating it and letting it act on its own.

During the latest Communist Party Conference, President Raúl Castro asked us “to call things by their name and not seek refuge in illogical euphemisms to conceal reality.” The idea was made explicit in the Conceptualization of Cuba’s Economic and Social Model for Socialist Development, allowing the possibility of establishing small and medium enterprises under that type of ownership.

What’s needed now is changes in regulations and in mindset.

In Pérez’s opinion, under the conditions of economic recession that Cuba is going through, we must take advantage of whatever internal reserves we possess, no matter what the forms of ownership are.

“In socialist economies, such as Vietnam and China, the role of the private sector is very important,” he says, “and in no way has it destabilized the government. On the contrary, both countries move forward with high rates of annual growth.”

To do this, Pérez adds, the PYME have to be linked to the entire entrepreneurial environment, which has to be redesigned and instrumented in such a way that the State can recognize their role and create the conditions to utilize their entire potential.

Self-employed entrepreneurship resumed its march six years ago freed from the appellation of “necessary evil,” but the loose ends that hamper its normal functioning have not yet been tied.

One of those many loose ends is the lack of employment agencies, a mechanism that connects the owners of businesses with job-seeking individuals.

According to a study (2) done by teachers at the Center of Studies on the Cuban Economy, procuring employment in this economic sector is hindered by a changing reality where the non-state sector is called upon to furnish 60 percent of all Cuban workers, as stated at the start of the reforms.

A change in this regard could lead to an increase in productivity, the study reveals, because so far the private entrepreneurs who hire workers select them from the social networks, where the stress is on reliability, not necessarily competence.

Another observation is that equity is not served in job accessibility, because the jobs that tend to be more attractive (in economic terms) depend on the information and influence possessed by the social networks that are available and can be mobilized by an individual.

And this “disconnected” scenario can later become more evident.

Figures compiled by researchers Dayma Echevarría León and Mayra Tejuca Martínez (3) on the estimated demand for workforce 2014-2018 indicate an excess of graduates from trades that apparently are not included in the job descriptions published. Hopes are that they can find placement in non-state occupations.

The situation will remain contradictory and worrisome while the private sector continues to be isolated from the nation’s design of its job needs, above all while the options of employment remain restricted, on a frozen list that ignores the Cuban worker’s ingenuity.

———

(1) “A new economic model in Cuba; the role of the private sector,” Ricardo Torres Pérez. In “Glances Into the Cuban Economy; An Analysis of the Non-state Sector,” Havana, 2015.

(2) “Employment policies in Cuba 2008-2014; Challenges of equity in Artemisa,” Dayma Echevarría, Ileana Díaz and Magela Romero. In “The Cuban Economy; Transformations and Challenges,” Social Sciences Publishing House, Havana, 2014.

(3) “Education and Employment: Current and future challenges,” Dayma Echevarría León and Mayra Tejuca Martínez.” In “Economy and Management in Cuba; A Research Preview,” Biannual Bulletin, Jan.-June 2016, Center of Studies on the Cuban Economy.