Díaz-Canel in China and the Guangdong temptation

The Cuban president was in China to attend events commemorating the 80th anniversary of the victory in the Chinese People's War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression and World Anti-Fascist War.

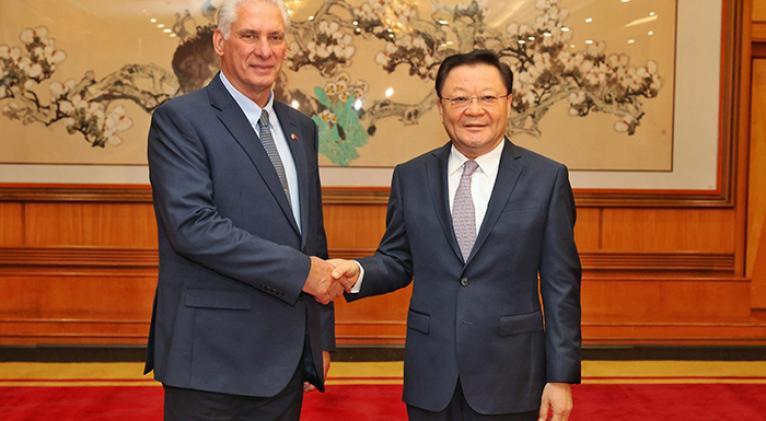

Cuban President Miguel Díaz-Canel visited China in early September 2025 to attend events commemorating the 80th anniversary of the victory in the Chinese People’s War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression and World Anti-Fascist War. The visit also marked 65 years of diplomatic relations between the two countries.

The visit attracted significant international attention. However, it was Díaz-Canel’s stop at Guangdong province that generated the most speculation. Could Cuba be contemplating a shift inspired by China’s most notable economic transformation as the island nation faces one of its worst economic crises in decades—marked by soaring inflation, frequent power outages, and an unprecedented wave of emigration?

Díaz-Canel’s words in Beijing seemed to suggest more than just diplomatic politeness. During meetings with Guangdong Governor Wang Weizhong, the Cuban leader emphasized the importance of “exchanging experiences,” specifically mentioning Fidel Castro’s 1995 visit to the region. The message was clear: Cuba is seeking a way out of its economic troubles—and Guangdong could have some of the solutions.

The Guangdong Model: Reform Without Revolution

To grasp the symbolism behind Díaz-Canel’s stop in Guangdong, one must look back to the late 1970s, when China, under Deng Xiaoping, launched an ambitious experiment in “Socialism with Chinese characteristics.” Guangdong, being close to the capitalist Hong Kong and having a population eager for opportunity, was chosen as a testing ground for reform.

Cities like Shenzhen, once a quiet fishing village, were transformed into global megacities through the creation of Special Economic Zones (SEZs). These zones were given more freedom to attract foreign investment, offer tax incentives, and implement business-friendly policies—while the Chinese Communist Party maintained tight control over political power.

It was a grand bargain: economic opportunity in exchange for political obedience. The results were spectacular. But can Cuba—an island nation with very different circumstances—hope to achieve anything similar?

Cuba’s Stumbling Start: The Mariel Disappointment

Cuba has experimented with its own version of economic reform. In 2013, it launched the Mariel Special Development Zone, promoting it as a future hub for foreign investment. A decade later, however, the project has stalled. Red tape, centralized decision-making, and a lack of legal transparency have discouraged investors.

Díaz-Canel’s trip to Guangdong might indicate an intention to revisit and expand this model—potentially establishing new SEZs or loosening regulations further. However, critics emphasize that without genuine structural changes, these efforts are likely to fail again.

Can Cuba Really Become the Next Guangdong?

The gap between Guangdong in the 1980s and Cuba in 2025 is huge. China gained access to international capital through Hong Kong and could send millions of migrants to work in its factories. In contrast, Cuba has an aging and shrinking population, poor infrastructure, and is almost fully isolated from global markets.

Additionally, Cuba does not have the industrial base and technological ecosystem that helped Guangdong thrive. Trying to copy the Chinese model might be inspiring— but it’s also very unrealistic given the current circumstances.

A Political Gamble: Prosperity Without Pluralism?

Beyond economics, a much more sensitive issue is politics. China’s transformation did not include democratic reform. Instead, it strengthened authoritarian control with new tools—digital surveillance, censorship, and state-led nationalism.

Could Cuba be planning a similar path—economic opening without political liberalization?

Cuban civil society disagrees. Over the past decade, more citizens have demanded more than just economic improvement. They seek freedom of speech, political options, and human rights. A Guangdong-style opening might bring short-term economic gains, but it is unlikely to satisfy a public that is increasingly aware of what’s possible in a more open world.

Cuba at a Fork in the Road

Díaz-Canel’s reference to Fidel’s 1995 visit to Guangdong is full of symbolism, but history doesn’t always repeat itself. Cuba in 2025 isn’t the same as Cuba in 1995. The population is more digitally connected, more disillusioned, and more eager for real change.

If Díaz-Canel is serious about reform, he faces a choice: adopt a model that prioritizes economic growth under ongoing one-party rule or look toward Eastern Europe—toward the Balcerowicz Plan in Poland, the Czech Republic’s shock therapy, or the Baltic states’ quick path to EU integration. These imperfect transitions still resonate more strongly with citizens who dream not just of prosperity but of dignity, democracy, and self-determination.

Conclusion: Between Reform and Resistance

Díaz-Canel’s visit to Guangdong is more than just a diplomatic gesture—it signals that the Cuban government is looking for answers. However, by borrowing from China’s playbook, Havana risks adopting a model that offers only partial solutions: economic survival without political legitimacy.

As the Cuban people continue to face hardship and push for change, the question remains: Will the government deliver reform—or just another illusion of it?