Cuba’s new rules for information and communications technologies

HAVANA – On July 4, the Island’s Official Gazette published a decree law, two decrees, an agreement of the Council of Ministers, and six resolutions to regulate, through unique legal instruments, the development and use of information and communication technologies in Cuba.

In 2017, the Council of Ministers approved the Informatics Policy, an immediate antecedent of the new laws published. “The regulations establish the necessary legal framework to continue moving forward. They are an expression that consider the ICT (information and communication technologies) as a strategic axis of development. Cybersecurity is a key factor,” Cuban Communications Minister Jorge Luis Perdomo wrote in his Twitter account.

In February 2015, we learned that Cuba was working to define the conceptual and normative instruments that would guide the country’s informatics process. It is reflected, and not with the clarity required, in this series of legal instruments, which address issues very present in the public agenda of today — things such as the software industry, content dissemination on the internet, cybersecurity, as well as electronic government and electronic commerce.

The biggest controversy regarding the new rules for information technology and cybersecurity is said to be the contraventions associated with ICT established in article 68 of Decree-Law 370. Most controversial are: Section (F) which declares the “hosting of a site on servers located in a foreign country, other than as a mirror or replica of the main site located in servers on national territory” a violation; and Section (I) which also cites as a violation “the spread, through the public networks of data transmission, information contrary to the social interest, morals, good habits and integrity of the people.”

The biggest controversy regarding the new rules for information technology and cybersecurity is said to be the contraventions associated with ICT established in article 68 of Decree-Law 370. Most controversial are: Section (F) which declares the “hosting of a site on servers located in a foreign country, other than as a mirror or replica of the main site located in servers on national territory” a violation; and Section (I) which also cites as a violation “the spread, through the public networks of data transmission, information contrary to the social interest, morals, good habits and integrity of the people.”

In reference to the first example (Section F), the same day the regulations were published the Ministry of Communications tweeted a clarification stating that “in the case of natural persons, it refers to the national platforms and applications of services offered on the Internet and used by citizens, it does not refer to blogs, personal or informative sites.”

Dozens of Internet users have expressed their dissatisfaction with this definition, stating that this is not clear enough since an explanation given on a social network is not an official amendment, and what is in force is a legal norm that can be interpreted arbitrarily.

Regarding the second section (I) mentioned, many have asked that this section be better defined. Because one could ask what is considered “information contrary to the social interest, morals, good morals and integrity of people?” Many opinions diverging from the government positions could be considered a violation, thus limiting the fundamental right of expression of the Cuban citizenship, recognized in the new Constitution.

The fine for this infraction is 1,000 Cuban pesos (about 40 U.S. dollars) and / or the “confiscation of the equipment and means used.”

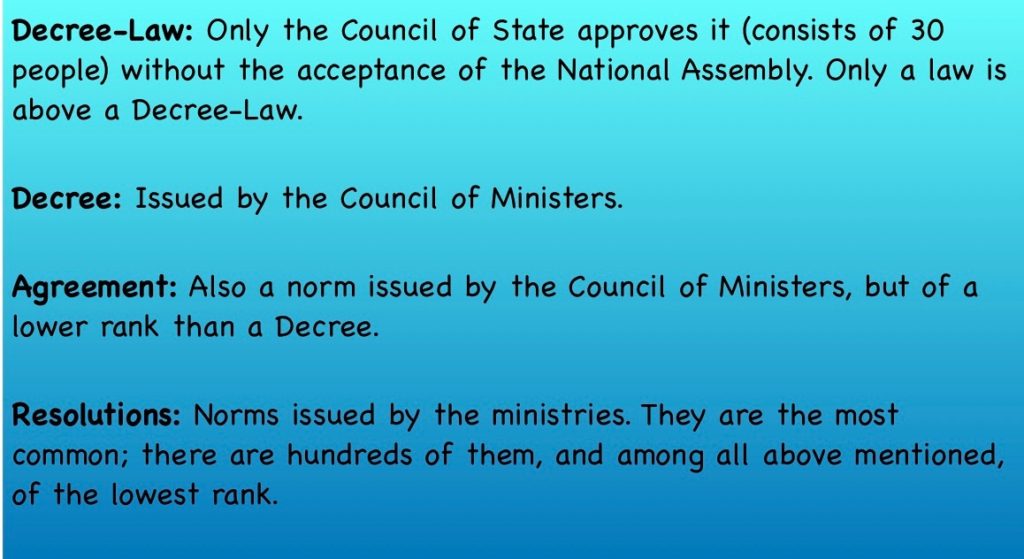

The new Decree-Law is part of a government tradition, which regulates cardinal aspects for Cuban society with legal norms that do not need the approval or revision of the parliament, but can be approved and enforced by the Council of State, which represents the National Assembly of People’s Power (ANPP) between the two ordinary sessions held each year.

In 2019, only the Fishing Laws, the National Symbols Law and the Constitution of the Republic have been approved by the ANPP; meanwhile, more than 10 Decrees-Laws have been issued by the Council of State.

Ernesto Vallín Martínez, director of the Informatics Industry of the Ministry of Communications (MINCOM), explained that the legislation aims to keep the state enterprise in a lead role in the production of computer solutions, although the current context facing the country is not very promising in that sense. According to official figures, in recent years Cuba has graduated more than 47,000 web developers, most of them from the University of Computer Science. Although many work in state institutions, it is also well known that a good part of these professionals have decided to emigrate, or have taken jobs in the non-state sector.

Something new is that the existing regulations incorporate the validity of digital signatures, although only for legal entities, and according to the document, “with the use of digital certificates of the public key to national infrastructure.” This last aspect will be key in the creation of a single electronic registry that streamlines the process of natural persons in various instances.

It also places in black and white the country’s migration to open source and national production, both in terms of operating systems and specific antivirus systems. In fact, said Miguel Gutiérrez Rodríguez, of the MINCOM, that transfer must happen in the organisms of the administration of the State at the latest in three years. He said that only this ministry will be authorized to grant extensions.

Cuba’s transition to the use of free software was an intention expressed by the Council of Ministers in 2004, when it agreed to begin on that path without establishing a deadline. If the provisions of Decree 359 are fulfilled, it would take place before 2022. However, abandoning dependence on proprietary software is not exempt from inconveniences and cannot be an abrupt process in practice.

More time will be needed to evaluate all the implications of this package of administrative, organizational, physical, legal and to a certain extent educational measures, whose premises continue to be focused mainly on technology.

One could then ask why, if the National Assembly was in session, they did not discuss the topic and vote on it.