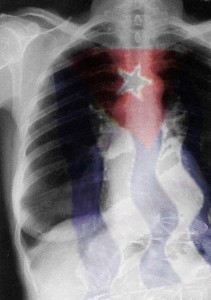

Baseball and the Cuban heart

Leonardo Padura and Guillermo Rodríguez Rivera at bat. Progreso Weekly publishes the reflections of two great Cubans, both fans of baseball and Cuba. They write their views about the game that could be held the next weekend in Miami and Tampa as homage to the 50th anniversary of the Industriales team and that will get together on the field players from both sides of the Straits in an unprecedented event.

Leonardo Padura and Guillermo Rodríguez Rivera at bat. Progreso Weekly publishes the reflections of two great Cubans, both fans of baseball and Cuba. They write their views about the game that could be held the next weekend in Miami and Tampa as homage to the 50th anniversary of the Industriales team and that will get together on the field players from both sides of the Straits in an unprecedented event.

Baseball and the Cuban heart

By Guillermo Rodríguez Rivera

From Segunda Cita blog

My friend Leonardo Padura has published a good article –as his writings usually are– in which he comments on the vicissitudes of a project for a baseball game in Miami in which veteran players of the Cuban Industriales team that reside in Cuba would face those Industriales vets that now live in the US.

What Padura calls a “bold” idea of a Cuban impresario. a resident of Miami, had the immediate acceptance of players from both sides of the Straits, many of whom played together and obviously are eager to meet.

The project was also accepted by Cuban authorities who gave their approval –according to Padura, “with no kind of official affirmation”, “as if it weren’t happening”. The problem came up with the acceptance of exiled Cubans. I believe that the overwhelming majority of Cubans in Miami would be anxious to see these retired athletes, whose feats they admired years ago.

But exile groups, “a minority, although powerful”, were opposed to a game or two to be played, claiming that two of the ballplayers that would arrive from Cuba had attacked –15 years ago– a Miami Cuban resident who in Canada jumped into the field where Cuba was playing “carrying a banner of a political character.”

From his correct point of view, Padura reasons over what he calls the “political blindness” of those exiles for:

… not having the ability to grasp the social and political significance for Cuba and its future, and the importance of fraternization in the field by players, both émigrés and the ones who have remained in the country

But although definitely it is historic blindness, it seems to me that those exiles are assuming a different political perspective –the perspective of those who do not want that fraternization to happen, because it goes against their interests.

Padura explains that resentment in the following manner:

Too many years of encystations, of hate, of a need of revenge, of mutual insults and humiliations (the ones over there gusanos [worms], unpatriotic, traitors; the ones over here, communists, repressors, co-conspirators with Castro, etc.) have been building up and still muddle the present and the future of the different parts into which the heart of this Caribbean island has been broken.

And this is my discrepancy with Leonardo’s approach.

I pride myself on knowing and having studied the way Cubans behave. And I know that the mindset of a people is, besides the factors that are part of its constitution, the result of the history that has influenced them

No Spanish-American country fought more against Spain for its independence than Cuba. And few nations suffered so barbarous and inhuman repression, such as the execution by drawing lots of eight medical students in 1871, or the genocide that became the concentration of peasants ordered by Spanish General Valeriano Weyler in 1896. However, Cubans did not harbor hate against the Spaniards: after the creation of the republic, Cuba welcomed more Spanish immigrants than during colonial years. Those Spaniards settled on the island, here they found work, founded their families and many became Cuban citizens.

Aldo Baroni, an Italian politician at the time of the pre-revolutionary Republic, said once that Cuba was a “country with a poor memory.” Maybe we are, but I am certain that we are also a country of little rancor.

I do not believe that the actions of that group of exiles –“a minority, although powerful”– is evidence of what Padura calls “a fracture of the national soul”. The national soul is in those ball players –some have emigrated, others reside in their country– who long to meet and compete in the unique, emotional, fraternal fact that a ball game is for Cubans. That national soul is in the thousands of Cubans that would attend the game in Miami and in the other thousands that would pack the Latinoamericano Stadium if the game were played in Havana.

In those few (but powerful) exiles that threaten the sponsors of the game and also those who would dare offer a stadium so that the game can take place, there is something else above the “broken heart” mentioned by Padura, bringing to mind the song by Alejandro Sanz that years ago you could not escape from.

I believe there is something supplementary, something that is beyond or nearer to the soul in that inextinguishable rancor toward the Island displayed by a few exile groups in Miami that can materialize in the inexplicable hate toward a centerfielder.

It is a truth that those groups of counterrevolutionary fundamentalism are disappearing little by little, as those of revolutionary extremism have become extinct.

Its minority condition is obvious. The restrictions to family travel to Cuba and the remittance of money to relatives that Bush imposed and who were opposed by Barack Obama, determined that in the last presidential election, Miami-Dade County voted Democrat for the first time, instead of Republican. But the US budget still has appropriated several million dollars for backing groups that still maintain total rejection for revolutionary Cuba, including its actresses, its intellectuals, its bands, its musicians, its scientists, and its athletes.

These minority groups, besides the rancor they do not know how to abandon, keep an interest that places them among some hundreds of exiles that have made of the subsidy they receive their business and their way of life. That financing is what feeds that power that is violence –physical, economic, social– exercised against their fellow citizens, who have been taught that there are freedoms that are too expensive to practice in Miami. Thus the impossibility for the sponsors to find a stadium in Miami –loaned or rented– that would house the Industriales that want to play their nine innings.

It is time for Cuban baseball to take a step forward. Let us offer the Latinoamericano Stadium for the first version of this meeting between the Industriales that live in the US and the ones who live in Cuba. Let the Cuban Americans come to Havana, now that they have the opportunity to do it, and that fans from Miami and Havana also pack the Latinoamericano to see the old Industriales play.

The wounds from the War of Independence were not yet healed when tens of thousands of Spanish immigrants began to arrive, But the Cuban government had no budget to assist those who would fire up the hate against Spain.

Anyway, things are changing. A few days ago Cuba announced the possibility of calling Cuban volleyball players, under contract as professionals abroad, to come and play for our national team. They are world class athletes, formed in the Island. Likewise there has been an announcement that our baseball players will be authorized to sign contracts with professional teams, as long as they can also play in our National Series. That would exclude US teams, because the laws of the blockade –although Americans give the more aseptic and juridical name of “embargo”– prohibit anyone to work in the US while residing in Cuba.

A few days ago left-handed pitcher from Villa Clara Misael Siverio, abandoned the national team with which he had traveled to the United States before the start of a tournament. He declared that he wanted “to prove himself in the Major Leagues.” I don’t believe it’s reprehensible that an athlete would like to compete at the highest level in his/her sport, not that –although Siverio did not mention it– expect to be paid the big money of the Major Leagues. What is humiliating is the price that a Cuban has to pay for it.

It is a thing of the past for Cubans the times when Orestes Miñoso played the left field for the Chicago White Sox in the summer, and in winter played the same position with the Marianao Tigers in Havana.

When in 1959 the Revolution came into power, Cuba had eleven players in the Major Leagues –more than any other Latin American country. I tried to recall and realized that in recent times “El Duque” and Liván Hernández, José Ariel Contreras, Kendry Morales, Rey Ordóñez, Yaser Gómez, Yadel Martí, Miguel Alfredo González, Yasiel Puig, Haroldis Chapman, Yunieski Maya, Alexei Ramírez, Maels Rodríguez, Yoenis Céspedes, Dayán Viciedo have gone on to play abroad, particularly in the US. Almost all of them are young people of humble origin that became athletes in our schools and were formed as first class ball players, and as such were hired by organizations of US professional baseball.

Cuba will keep on forming world class ball players, especially if we have a better organization of our National Series and create a higher standard of competition. We are entering a new moment in which professional baseball has fused with amateurism and has dominated the latter, although in truth our best players were not professionals, but were no longer amateurs. When a player reached the highest level in our country, he only worked as an athlete, even if he was not paid the high salaries of professional baseball.

Forming a baseball player does not give Cuba the right to having him at its disposal forever, if the athlete wants and has the possibility of playing in other places that increases his professional hierarchy and his style of life and of his family. Cuba cannot preserve his excellent players competing against their material wellbeing that the United States can offer a Cuban player, which turns the baseball player into another tool of the war against the anti-imperialist island.

Cuba only has the possibility of calling all Cuban baseball players that live and play abroad, the ones it formed, even if they are playing now in the US Major Leagues. It can appeal to the athlete’s love for his country and should never close the doors to him, but always calling to play for his country. Let others be the ones to forbid them from doing it. That will also be a struggle over there against the economic, commercial and financial blockade that Washington imposes on us.

Cuba should also include those Cuban players that were at the highest level in the US and now are not, but still have the quality to be part of our national team and wish to do so.

Up to now we have been on the defensive. Cuba should take the offensive, fighting with our moral values: love for Cuba, and the player’s sense of belonging.

You can live somewhere else and benefit economically from work there, but it does not mean that you have renounced to be Cuban, to defend our flag and to feel the pride of playing for it. Let us battle for it with the whole heart that Cuba has.

********

Cuba, a Country with a Broken Heart

From IPS

HAVANA (IPS) – For Cubans, baseball is not a sport, much less a game: it is almost a religion, and taken very seriously.

Baseball was brought to Cuba around the mid-19th century by young men whose families had sent them to study in cities in the United States.

Back then, “el juego de pelota”, as it was called in Cuba, had crucial importance in different areas of the national spirituality: as a non-conformist social activity that indicated a desire for progress (United States’ modernity in contrast with the backwardness of Spain – the former colonial power); as a manifestation of national unity, because very soon it was played all over the island; and as a means of bringing together social classes and ethnic groups (because Afro-Cubans and peasants soon became devotees of the game).

It was also a performance in which sport and culture came together, thanks to the entertainment provided by “orquestas de danzones” (bands playing the Cuban national dance), the design of baseball teams’ uniforms, modernist pennants and graphics, and the artistic and journalistic literature devoted to commentating on and promoting the sport.

For Cubans, baseball has been the most played and most beloved of sports, the one that has given rise to the most legends and has carried the greatest social weight. In recent years it has also been (as it could not avoid being) a battleground for some of the most critical political, social and economic conflicts taking place in Cuban society.

Several dozen Cuban players have taken the risk of being branded “deserters” or “traitors” by official rhetoric, deciding to depart the island to try their fortunes in other leagues (especially in U.S. Major League Baseball). This has caused a commotion in Cuban society and sport, which cling to the models and politics of amateur sports followed in the socialist countries.

The departure of these players from the country has had three basic consequences.

One, for sport: a drain on regional and national teams, since a “deserter” is banned from returning to represent his or her club or country at any official event.

Another, economic: while athletes on the island earn the salaries of “amateurs”, those doing well abroad can sign contracts worth (many) millions of dollars, and even those whose performance is less outstanding can earn at least several hundred thousand dollars a year.

And thirdly, political: the Cuban government, without essentially modifying its sports policy, has begun to allow baseball players to be contracted for professional tournaments abroad (although not for the Major Leagues).

The perpetual tension of baseball politics allows this sport to express, in a quantitative way, the distance between Cubans living on the island and those who have left it in search of new horizons.

Its overwhelming influence in Cuban society and spirituality transform it, together with its cultural expressions, into one of the facets of Cuban life where any moves toward reconciliation and communication have special connotations, capable of influencing every order of life, including politics.

Recently a Cuban businessman living in Miami had the bold idea of holding two or three baseball games in the southern U.S. state of Florida among retired players of Cuba’s most emblematic club of the last 50 years, the Havana Industriales.

The novelty was that they would play on the other side of the Florida Strait and the intended participants would be former players living both within Cuba and outside the country – that is, the so-called “deserters.”

The first step would be obtaining permission from the Cuban authorities for the players to meet and play against their former teammates. Without official confirmation, it was understood that permission had been granted, but silently, as if nothing were going on.

The second step was up to the other side of the Strait: would Cuban exiles accept the presence of Cubans living in Cuba at a public event?

From the outset, former players living outside of the country were favourably disposed to the idea, to the satisfaction of most of the Cuban exiles, who looked forward to seeing their old idols again. However, a small but powerful minority of the exiles were against the proposal.

That is when the event promoters’ tortuous ordeal began, as in addition to receiving threats of all kinds, they have had to wander the city of Miami looking for a baseball field to hold the matches in. But the promoters vow that the event will be held, “even if it is in a canefield.”

To lack the capacity to see the momentous social and political significance for Cuba and its future of having émigré players and those who have remained in the country fraternise on a baseball field is an attitude of political blindness. But I believe, above all, it is an expression of a fracture of the Cuban national soul that is so deep, so charged with resentment, that not even something as sacred as baseball can easily mend it.

Too many years of deadlock, hatred, desire for revenge, and exchanges of insults and abuse (those who left the country are “gusanos” or worms, turncoats, traitors; those who stayed behind are communists, oppressors, Castro accomplices, etc.) have accumulated and still muddy the present and future of the different fragments of the broken heart of this Caribbean island nation.