The Cuban-American transition: Demographic changes drive ideological changes

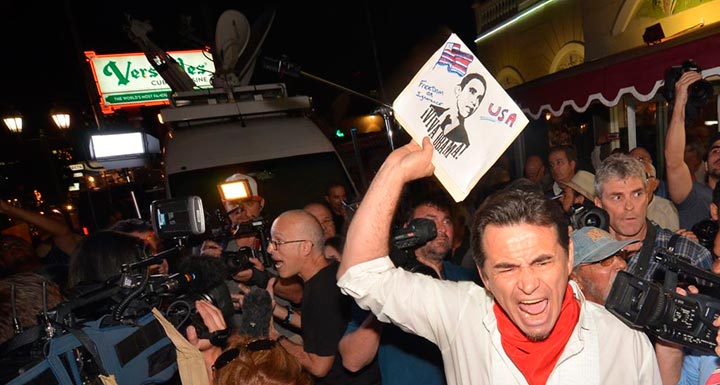

MIAMI – The recently proposed changes to U.S. Cuba policy have been viewed by critics as being a capitulation to the government of Cuba and by supporters as a long needed adjustment to a failed policy inspired by Cold War geopolitics. Some in both camps consider it a risky move by President Obama. The risk involved is the alienation of the Cuban American electorate in South Florida which might put the 2016 democratic presidential candidate in a precarious position to win the third most populous State in the elections.

Supporters of the vision point out that the Cuban-American community in South Florida is changing and its long-held hardline attitudes have been tempered by time and a demographic transition that is driven by second generation and new migrants from the island. Much of the empirical evidence for the argument supporting changing views comes from the FIU Cuba Poll, a poll which has tracked Cuban American attitudes about U.S. Cuba policy.

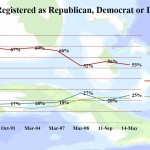

Since 1991, the FIU Cuba Poll has measured the attitudes of Cuban-Americans living in South Florida towards U.S./Cuba relations. Despite the controversy that often surrounds the poll, the research has contributed to the understanding of the changing nature of Cubans in the United States. Before the Cuba Poll, Cuban Americans were frequently characterized by their monolithic ideological “right wing” leanings. This “Exile Ideology” shaped the national perception of the nature of the Cuban American community. Non-Cuban-Americans characterized Cubans in the Miami area by their political features: staunch anti-Castrism, militancy and political conservatism. The image was reinforced by their overwhelming political allegiance to the Republican Party.

In this brief essay I present some of the results of the latest poll-May 2014 – on the views of the Cuban community in Miami to Cuba and to the U.S. policy with the island. I compare some of the key responses to previous surveys conducted since 1991 to contextualize some of the changes in the community over the past twenty years.

There are Cubans and there are Cubans

In recent decades the Cuban community has grown increasingly diverse. Since the Mariel Boatlift in 1980 and, more recently, since the regularization of immigration by the 1995 Immigration Agreement, the Cuban population of Miami has developed socioeconomic characteristics unlike the earlier arrivals. For example, analyses of income differences among the pre-Mariel, and the Mariel and post-Mariel cohorts of Cuban immigrants, reflect stark contrasts indicating different modes of economic incorporation (Portes and Puhrmann). More surprising is the fact, that after decades of a strong alliance to the Republican Party, recent studies point to an increasing growth of support for the Democratic Party and Independent affiliation among Cuban Americans.

The ideological diversity of the community is increasing as well. This change is driven by the flow of immigration established by the 1995 agreements and the rather unusual mode of receiving these immigrants provided by the Cuban Adjustment Act of 1966. The special legal status afforded to Cubans was given legal grounds on 2 December 1966 when President Johnson signed the “Cuban Adjustment Act” – providing that “any alien who is a native or citizen of Cuba and who has been inspected and admitted or paroled into the United States subsequent to 1 January 1959 and has been physically present in the United States for at least one year, may be adjusted by the Attorney General at his/her discretion and under such regulations as s/he may prescribe for an alien lawfully admitted for permanent residency…”

In other words, the Cuban Adjustment Act establishes that any Cuban arriving in U.S. territory, even illegally, and residing there for two years (it was later shortened to one year and it is still effective) can receive the status of permanent resident in the United States.

Cubans are the only immigrant group that automatically and immediately receive a working permit, do not have to submit an affidavit of support to become lawful residents, get a social security number and public benefits for food and accommodation, adjusts their status without having to return to their country of origin to receive it and do not need lawyers or money to get the benefit of blanket parole. The CAA might be the only law in effect in any modern society that offers these privileges to a migrant group not threatened with physical extinction.

This policy has provided an irresistible “carrot” to Cubans discontent with their lives on the island and it provides a significant “stick” for the Cuban government to use against the United States while encouraging the exit of its dissidents and malcontents. The result of this policy has been the constant flow of Cuban nationals to the United States for over fifty-five years. It is this flow that has changed the character of the Cuban-American population from exiles to immigrants and is changing the ideological and political landscape of the community.

The shift in policy ushered in under the “normalization” agreements of 1994-1995 have increased dramatically the flow of Cubans to the U.S. as well as introducing an important change in the provisions of the Cuban Adjustment Act. The 1995 agreements committed the United States to admitting a minimum of 20,000 Cubans per year and adjusted the CAA by introducing what has been called the “wet foot, dry foot” policy to discourage unregulated migration from the island.

Under the “wet foot/dry foot” policy Cubans who make it to shore can stay in the United States – likely becoming eligible to adjust to permanent residence under the Cuban Adjustment Act, but those who do not make it to dry land can be repatriated unless they can demonstrate a well-founded fear of persecution if returned to Cuba. Although the agreements created an “illegal” dimension to Cuban migration that did not exist previously, it also normalized the flow of migrants. (The minimum number of admittances does not include the admission of immediate relatives of U.S. citizens.)

During the Bush years, legal migration never reached the agreed upon totals. The Washington Post reported that in 2003, only 700 Cubans had been admitted during the first quarter of the year. (Washington Post, 2003:A21) Despite this hiatus, the first decade of the 21rst century was the most active in Cuban migration history (Wassem, 2008:15). (Figure 1)

This population displacement is important for several reasons. As shown in Figure 2, the continuous migration from the island since 1959 has transformed Miami-Dade County into the largest metropolitan area in the U.S. composed mostly of ethnic minorities. Over eighty-five percent of the population belongs to a minority group. Cubans stand out as the largest minority group. More than thirty-five percent of the population of Miami is Cuban, and “newcomers” arriving after the signing of the 1995 migration agreement comprise more than thirty-five percent of the Cuban population. But even this number understates the importance of the Cuban population in the Latinization process of Miami. As shown in Figure 3, Cubans are the largest Latino group in the county; only six other national groups represent more than two percent of the total county population.

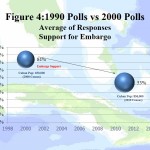

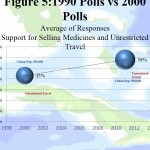

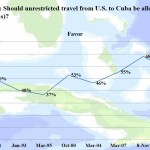

The persistent Cubanization of Miami is significant because it is the driving force for change in the ideological profile within the community, particularly in their attitudes towards Cuba and its government. If we take the average of the five surveys conducted during the 1990s and the six surveys we conducted since 2000, we see some basic trends. Figure 4 shows the average of the support expressed for the embargo during the two decades of surveys and the number of the approximate population of Cubans in Miami at the time of the surveys according to the U.S. Census. In the 1990s, when the number of Cubans in Miami totaled 650,000, an average eighty-four percent of respondents supported the embargo. Over the next decade, support declined to an average of fifty-three percent as the population of Cubans in Miami rose to 856,000. Figure 5 shows a similar impact of population density on the support expressed for unrestricted travel to Cuba by all Americans as the support increased from forty-three to fifty-eight percent. The density of the Cuban diaspora, fueled by newcomers, appear to be an important factor in the changing ideological profile of the community.

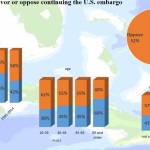

The changes in community attitudes toward the island can be clearly seen when comparing the survey responses over the past two and a half decades. Figure 6 presents the weakening of support for the embargo during this time. The importance of demographics in this change is evident in Figures 7, drawn from the 2014 poll. Here we see conciliatory viewpoints expressed more frequently by newcomers (since 1995) and the younger generation of the Cuban diaspora. It is also important to note in this and other figures the tendency of voters. Voters are immigrants with more time in the U.S. Their attitudes tend to be more consistent with the characteristics of the classic “exile ideology” in their resistance to reconciliation. Newcomers, however, reflect more conciliatory attitudes.

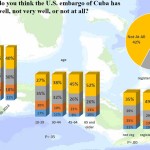

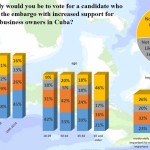

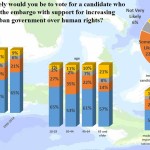

In another publication, I have explored the symbolic nature of support for the embargo and this dimension of the a characteristic often associated with a “hardline” approach to U.S./Cuba relations is evident in the 2014 poll when we consider how effective the respondents consider the embargo to be. As Figure 8 shows, an overwhelming majority of Cubans in Miami (Eighty percent of post 1995 migrants) believes that the embargo has not worked very well or at all. Perhaps because of this belief in the inefficiency of the embargo, a large majority of Cuban-Americans are willing to use the embargo as a negotiation chip for other policies that might be more effective in promoting changes on the island. Fifty-eight percent are willing to vote for a candidate who proposes to replace the embargo with a policy that increases support for small business owners in Cuba (Figure 9) and eighty one percent are willing to support a candidate who devices a way to increase pressure on the Cuban government over human rights’ concerns as a replacement to the policy of embargo (Figure 10).

The controversial issue of travel also responds to migratory pressures, as the trend line shows (Figure 11). In 2014, approximately sixty-nine percent of Cubans in Miami supported unrestricted travel to Cuba for all Americans (Figure 12). Newcomers are more interested in restoring freedom to travel for all residents of the United States.

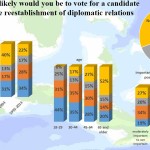

A major change in diplomatic policy toward the island is supported by the majority of the population. Approximately 68% supported the reestablishment of diplomatic relations with the Cuban government. Young Cubans as well as newcomers and Cuban-Americans are the most convinced of this change (Figure 13). When registered voters are asked if they would vote for a candidate who supported establishing diplomatic relations, most young and new arrival Cuban-Americans answered that they would like to do so. (Figure 14)

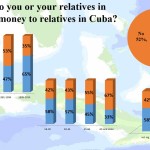

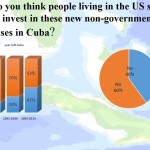

Remittances are an important feature of the diaspora/homeland relationship. Figures 15 and 16 present respondents categorized by the annual amount sent to relatives on the island by time of arrival. Again, we see the importance of the new immigrants in economic transactions. Newcomers send more remittances than any other category (65%) and send a higher average amount than other groups—31% send over $1000 a year (Figure 16). This commitment to the development of the Cuban economy is also reflected in attitudes towards new investment opportunities on the island created by the structural economic changes underway in Cuba. Significant numbers of Cuban Americans show a desire to support and take advantage of investment opportunities on the island (Figures 17 and 18).

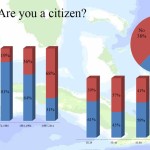

Ultimately, Figures 19 and 20 present the data most important to the process of changing national policy toward Cuba. Although the Republican Party, traditionally regarded as the most intransigent toward a policy change is decreasing absolute control over Cuban-American voters (Figure 21), newcomers are not represented in the register of voters in sufficient numbers to play an important role in altering policy toward Cuba. Only 31% of newcomers have become citizens. Once they become citizens, however, the most recent arrivals follow the pattern of previous waves and register to vote; 83% of the eligible post-1995 arrivals are registered.

Conclusion

Any synthesis of Cuba Poll surveys leads to the same conclusion: demographic changes are driving the ideological changes of the Cuban community in Miami, but the ideological changes will not be reflected in electing politicians who reflect these changes until new waves of immigrants join the second-generation Cuban-Americans in expressing their wishes at the polls. When this happens, the exile ideology will give way to a new ideology based on the recognition that the Cuban diaspora is an extension of the nation with responsibilities and duties to the civic, cultural, economic and political development not only of Miami-Dade County, but in Cuba.

This is important because the trends could signal the end of the tendency to see the community as ideologically monolithic and uncompromising, and the emergence of the “new transnational ideology of diaspora” directed at establishing and maintaining relationships with the island. If it is true that the old exile ideology has exerted a major influence not only in the development of an immigrant community, but also on the foreign policy of the United States, the bearers of the new ideology will wield similar power.

Just like Reagan mobilized the Cuban-American community in the 1980s around national enterprise of destroying “the evil empire” of the Soviet Union, so can the contemporary Cuban community be mobilized around the more creative endeavor of contributing to the development of a 21rst century Cuba. Regardless of the actions of institutions, however, Cubans in the Miami area are changing and for them a future with permanent links to the island is the only option.

Guillermo J. Grenier, Ph.D., is Professor of Sociology and Graduate Program Director in the Department of Global & Sociocultural Studies in the School of International and Public Affairs at Florida International University.