Cuba wants clean energy. Can the U.S. deliver?

As Cuba attempts to end half a century of isolation, another momentous shift is happening. The communist island is making earnest plans to clean up parts of its fuel supply, moving from crude oil to a portfolio of wind, sun and sugar cane.

The United States is the dominant energy provider in the Caribbean and has more renewable energy expertise than almost anyone. Is Cuba its next partner?

Cubans and Americans who spoke for this story reveal a picture of frustrated desire. At an energy conference here last month, the United States was mentioned again and again as a model for development, but no American businesspeople were present to hear. American energy companies say they are keenly interested, but face such large unknowns that they can make no plans.

At stake is the energy supply for the largest island in the Caribbean. Cuba has a population the size of Ohio and plans to spend about $3.5 billion in the coming years to increase its supply of renewable energy. But despite the thaw in U.S.-Cuba relations that started last December, the island’s most ardent suitors are Russia and China, both of which are seeking to supply wind turbines.

Will the Cuban government follow the rules of global trade and make it worthwhile for foreign companies to invest? Will the U.S. Congress ease its embargo and let U.S. firms pursue dealsin Cuba — or will other countries beat them to it?

“The bureaucratics around this could take away the first-mover advantage for American companies,” said Andrew Holland, an energy and climate fellow at the American Security Project in Washington, D.C.

Cuba’s grand plan

At a renewable energy conference in Havana late last month, a senior official of Cuba’s energy ministry made it clear that getting off foreign oil is a high priority for the nation. Raúl García Barreiro, the vice minister of the Ministry of Energy and Mines, said that the government envisioned a chain of wind farms along the island’s north shore, numerous “bioelectric” stations using everything from sugar cane leftovers to pig poop, and solar installations of every size.

Other speakers hinted that everything is on the table when it comes to increasing the country’s renewable energy footprint. One said that Cuba could become an international supplier of wind energy equipment, while another suggested that the island could tap the output of giant solar farms in the United States through a subsea power line from Miami.

Meanwhile, Cuba is developing its own solar industry.

Outside the city of Cienfuegos, the government has built a manufacturing plant that has produced 14,000 photovoltaic solar panels. It has also constructed a 4.5-megawatt solar plant near the U.S. naval base at Guantanamo, according to José R. Oro, a former official with the Cuban industries ministry who is now head of Cuba research for Thomas J. Herzfeld Advisors, a Florida investment firm that maintains a mutual fund of Cuban investments.

The University of Havana is studying the prospect of Cuba running its own verification, control and certification labs for photovoltaic cells and modules, according to one conference speaker.

In his speech, Barreiro sounded notes that in the American context would have pleased both conservative Republicans and environmentalists.

He said that combustible fuels compromise the country’s energy independence and are the island’s primary source of contamination. He added that the high cost of energy, due to inefficient power plants and electric grid, is directly affecting the competitiveness of the national economy.

“It is urgent to increase the use of renewable energy sources to achieve in progressive form a change in the structure of the energy matrix of the country; reducing dependence on combustible fossils, energy costs and environmental contamination,” Barreiro said.

Cuba’s power grid is dirty and inefficient, the legacy of both its centrally planned economy and five decades of a U.S. embargo. The principal fuel is crude oil, pumped domestically and imported through a sweetheart deal with Venezuela. Many components of its electric infrastructure are decades-old relics from the United States and the former Soviet Union.

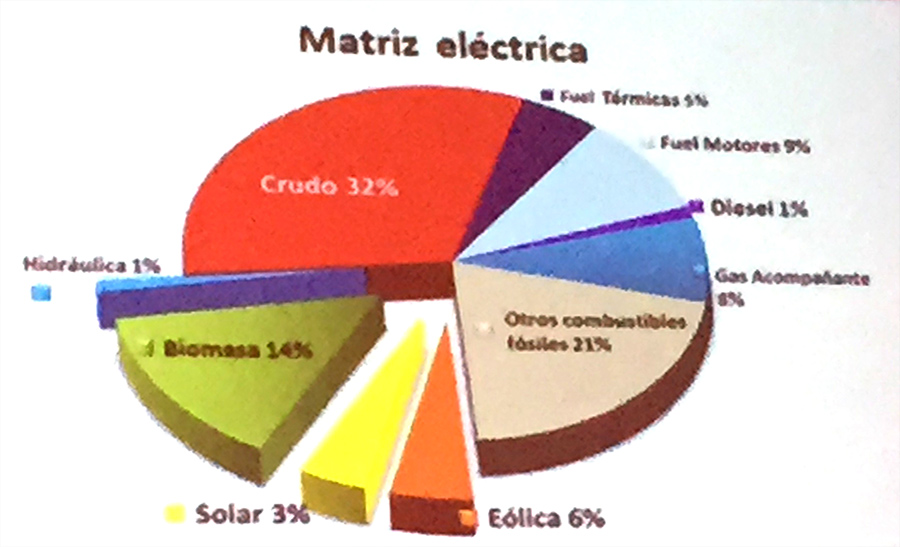

Today, only 4 percent of electricity comes from renewable sources, Barreiro said. But he laid out plans for a drastic ramping.

In 2012, he said, the government started crafting renewable energy goals to carry it through the period from 2014 to 2030. In August this year, it will begin to issue legal standards to support them.

The island plans to get to over 20 percent utilization of renewable energy by 2020, and by that time to get 14 percent of its grid power from biomass, 6 percent from wind, 3 percent from solar and 1 percent from hydropower. Meanwhile, Cuba seeks to reduce the cost of delivered electricity from $21.10 a kilowatt in 2013 to $17.90 a kilowatt in 2020, and reduce the grams of carbon dioxide per kilowatt from 1,127 in 2013 to 1,018 in 2020.

There is evidence that Cuba’s use of renewable energy is climbing steeply, said Daniel Stolik Novygrod, a photovoltaic specialist at the University of Havana. He said that Cuba’s production of renewable energy grew from 3.2 MW in 2012 to 30 MW in 2014, and may reach 700 MW by 2018.

The island wants 13 wind parks along the long north shore to produce 633 MW of wind, 19 bioelectric stations to produce 755 MW of “bioelectric” power and 700 MW of solar, Barreiro said.

Cuba also plans to expand its hydropower capabilities, despite having short rivers that leave few sites untapped. Presently, the island has 142 hydroelectric dams, 32 of which are connected to the grid. The government recently identified 74 new sites that could together produce 56 MW of electricity, Barreiro said.

In biomass, the country has four pilot power plants, and has a million hectares (almost 2.5 million acres) of land covered with marabú, a thorny and fast-growing bush that can be cut and chipped, and the residue from 67 sawmills.

Cuba has 1,818 biogas digesters and needs to build an additional 7,000, mainly using pig and cow waste. In addition, the country needs 500 industrial-sized biogas plants using the residue of distilleries, canning factories, sugar mills, slaughterhouses and pulping factories, the vice minister said. The energy ministry is also considering cogeneration at sugar mills and alcohol plants.

There are now 10,500 solar water heaters, mostly on tourist hotels, which may be augmented by an additional 100,000 square meters of heaters for farms and another 100,000 square meters for industry and other businesses.

On the efficiency side, the island has plans to install 13 million LED lamps in homes and 250,000 in public spaces, as well as introduce 2 million inductive stovetops to kitchens. In this, Cuba has a precedent. A decade ago, Cuba carried out a sweeping energy-efficiency campaign that replaced millions of incandescent bulbs with compact fluorescents, and replaced millions of aging and inefficient kitchen appliances.

In wind, university researchers are studying wind patterns to determine where to site wind parks and how to build the foundations — a difficult task in a country that must cope with the corrosive reality of salt air and the occasional knockout from a hurricane.

According to Delice Moreno García, the director of the Cuban government’s Electric Engineering and Project Co., known by its Spanish acronym INEL, Cuba is considering the possibility of manufacturing its own wind towers and components and competing with international providers in price and quality.

Overall, Cuba is planning to spend almost $1.3 billion on biomass, $1.1 billion on wind power and just over $1 billion on solar power, according to estimates by Oro.

Novygrod, the University of Havana solar expert, proposed that Cuba could follow the example of Europe, which has constructed 18 high-voltage direct current (HVDC) subsea cables to move electricity around the continent. He sketched three routes: down the chain of Caribbean islands to Venezuela, to the Yucatan Peninsula of Mexico or to the north, to make landfall just south of Miami.

For U.S. firms, a question mark

It is unclear what role American firms, or any large international companies, will play in renovating Cuba’s dilapidated power grid, or increasing its share of renewables. An example of that uncertainty is Vestas, the Danish wind energy giant.

Vestas was prominent at the Havana conference as one of the only private companies on the program, and the company’s Mexican representative, Carlos Redondo Rincón, gave a lengthy and optimistic presentation on opportunities in the Caribbean. But the company’s spokesman contacted after the conference said, “We don’t have a lot to say about the Cuba market at this point.”

“In Cuba, the wind blows and they need more power generating capacity, so at that level, the market has potential,” the spokesman, Michael Zarin, said in an email. “But it’s still early there.”

The same schizophrenic message is heard frequently in conversations about energy investment in Cuba: exciting, with rumors of scheming behind the scenes, but nothing concrete.

One tantalizing scenario for U.S. energy investment in Cuba comes via France. That country’s energy giant, Alstom, is going through the final stages of acquisition by General Electric. Oro said that Alstom engaged in talks with the Cuban energy ministry during a visit by France’s president, François Hollande, in May. However, a spokeswoman for Alstom said the company “has no project of development in this market in the short term.”

One U.S. solar company, Suniva, already has a presence in Cuba — at the U.S. naval base at Guantanamo. The company’s vice president of sales, Matt Card, said “it’s too early to tell” whether the company could expand elsewhere in Cuba, citing a lack of reliable information on how the government will act or how much power generation costs there.

The opening to Cuba that began with President Obama’s announcement in December has had real effects. Visits from the United States are up 36 percent this year, and the removal of Cuba from the U.S. list of countries sponsoring terrorism opens the door to certain trade and small-scale investment. Hardly a day goes by without news of some new thaw, fromsoccer to bank accounts to Airbnb.

A sailing race is one thing; the millions of dollars of equipment and loans required for large-scale energy projects is entirely another.

On the U.S. side, at least six laws enacted over decades have made it impossible for U.S. companies to trade with Cuba and have made it painful for foreign companies to do so. The arms of the U.S. government that would be best positioned to facilitate trade have their hands tied, because acts of Congress prevent them from factoring in Cuba.

A spokesman for the Overseas Private Investment Corp., a U.S. agency that supports international financing for U.S. firms, said, “We don’t have anyone here with experience or opinions to offer in the Cuban renewable energy sector.” The Bureau of Energy Resources, a part of the State Department that has pushed U.S. investment in the Caribbean, said its only coordination with Cuba is on response to oil spills.

“I would have thought that within the government there would be this sense of ‘what is the opening and what can we do,'” said Holland, from the American Security Project. “But so far we’re not getting that.”

Reliable sources of funds for giant energy projects in developing countries are the major multilateral banks, such as the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank or the Inter-American Development Bank. But Cuba isn’t a member of any of these clubs. While it’s not impossible for the nation to rejoin, it is mandated by Congress that the United States oppose any effort by Cuba to do so.

On the Cuban side, actions by the government over the decades have made investors wary. Cuba has struggled to honor its contracts and debts, and has made partial openings to foreign investment and then retreated. Many foreign investors have been dismayed by how slowly the bureaucracy moves in Cuba and have found that the government allows only the smallest of profit margins and maintains onerous employment rules.

However, some think that Cuba is doing it differently this time.

“They understand that they are by themselves and that they need to restructure the economy,” said Oro, the Cuban investment specialist in Miami.

Oro said, “We are seeing deal flow” and lots of interest among U.S. energy companies. He added that energy is one of the hottest areas for large-scale investment in Cuba, ranking after agriculture, construction and telecommunications, and on par with transportation. Energy investment in Cuba could reach $6 billion in the next few years, Oro said.

There are reports of meetings between Cubans and private companies, Oro said, where the Cuban representative is not a member of the politburo but a technical expert — a sign that the government intends to deal rather than posture.

Earlier this month, Cuba reached a breakthrough with the Paris Club, a group of wealthy donor nations including the United States, that may resolve Cuba’s debt from a major default in the 1980s.

While the Cuban government has long-term plans for renewable energy, the action right now is in natural gas, Oro said. The country’s existing power could be converted to run on natural gas, which burns much cleaner than the crude petroleum that is the country’s principal power supply.

The United States is building several terminals to export liquefied natural gas.

Oro said he had the sense that many non-U.S. companies were waiting to see what the United States will do, and would prefer to partner with a U.S. company. That’s partly as a matter of political cover, but also a sign of American dominance: The United States provides two-thirds of the electricity supply in the Caribbean outside Cuba, Oro said.

When international firms consider Cuba, Oro said, “most of them would be super-happy to do it with American companies and dilute the risk.”

(From: E&E)