Cuba and Venezuela: Economic relations and the possible impacts of U.S. aggression

Throughout the first quarter of the 21st century, Cuba’s economic relations with Venezuela have been very important. Their fundamental component has been the exchange of oil for medical, educational, sports, and technical services, along with some products and medicines from the biotechnology sector, under a scheme of “compensated trade” and preferential agreements. In recent years, the number of Cuban professionals in the service areas mentioned above has ranged between 20,000 and 40,000; in the early years of the Bolivarian Revolution, this figure was double the current amount.

It is important to note that there are no detailed public statistics on economic exchanges between Cuba and Venezuela; the data presented here are estimates based on scattered information published in various media outlets.

The persecution and harassment suffered by both countries at the hands of the United States have forced them to establish “clearing” (compensation) account systems and to make payments in kind to facilitate exchange.

The relationship has not been limited solely to trade; joint investments have also been carried out by both countries, in both Venezuelan and Cuban territory, across sectors such as energy, tourism, agriculture, communications, and others.

However, the levels of this exchange have declined since the 2008–2012 period due to Venezuela’s own economic problems and the very numerous unilateral sanctions imposed by the United States. After those years, daily oil shipments, which had reached as high as 100,000 barrels, were reduced to between 60,000 and 30,000 barrels, with values ranging from 800 million to 1.5 billion U.S. dollars. Total trade between both countries has remained between 1.8 and 2.8 billion U.S. dollars.

At present, the sharp escalation of U.S. aggression, the naval blockade, and the kidnapping of Venezuela’s president create, both in fact and by intention, major obstacles to the continuation of this exchange in the manner in which it had been developed. This will undoubtedly have a negative impact on the Cuban economy and will reinforce the causes of the crisis the country has suffered in recent years. The consequences would affect the energy sector and export revenues from medical and other services provided by the country, impacting more than 2 billion U.S. dollars in these areas. There could also be macroeconomic effects from a potential devaluation of the national currency stemming from reduced foreign currency inflows.

This situation would affect the national economy by reducing its import capacity—essential in areas such as food—as well as the functioning of the national industry due to energy difficulties.

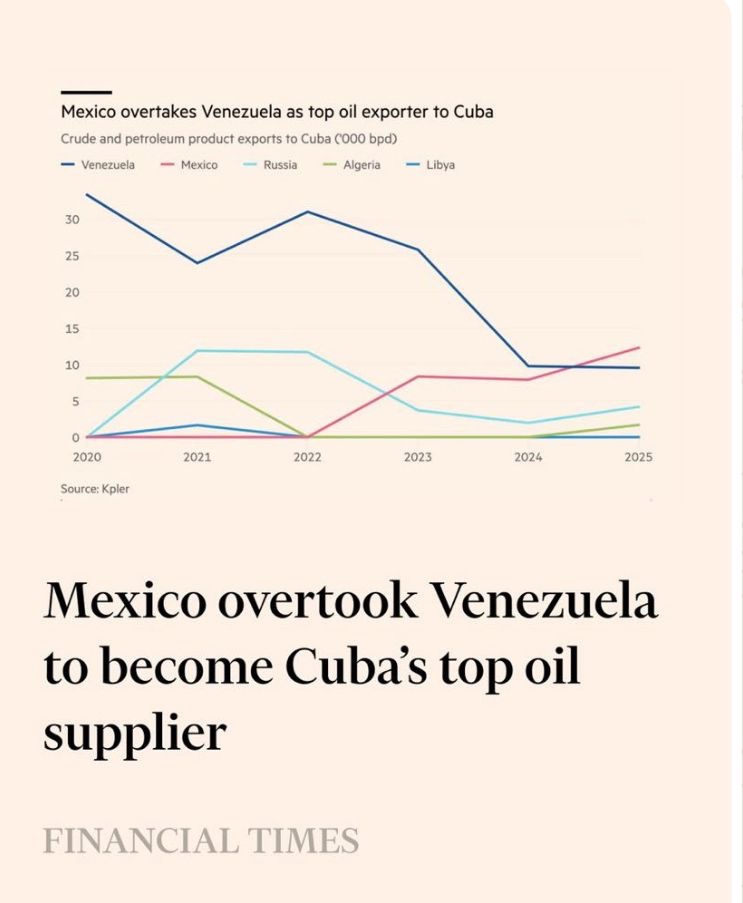

It should be noted, of course, that Cuba’s fuel supply does not come exclusively from Venezuela; shipments from Russia and Mexico are also significant. Mexico, in particular, has become a major supplier during the governments of the Fourth Transformation. However, given the instability of politics in the hemisphere, the stability of this supply cannot be guaranteed.

All of this situation—marked by risk, complexity, and uncertainty stemming from an increasingly imperial, aggressive, and irresponsible U.S. policy—should lead Cuba to accelerate its geopolitical and geoeconomic international integration with strategic partners such as China and Russia, among others, as well as within emerging spaces such as the BRICS. However, we believe that in order to achieve effective results in this effort, it is essential to accelerate and properly coordinate the deep economic transformations the country needs.

Note: As explained in the text, there are no detailed, official figures on economic relations between Cuba and Venezuela, which are presumed to be classified for security reasons. It must be noted that both countries are under unilateral sanctions and face a policy of aggression. The data have been drawn from various sources, including statements by leaders, academic articles, and press reports, and an effort has been made to be as precise as possible. Data on oil trade with Mexico comes from the Financial Times.

Julio Carranza Valdés holds a PhD in Economics from the University of Havana.

Julio Carranza Valdés holds a PhD in Economics from the University of Havana.