A crucial moment for Cuba’s tourism industry

HAVANA — Tourism was the most dynamic sector of the Cuban economy in the 1990s, with a remarkable progression in terms of foreign revenue and market share in the region. A noteworthy trajectory, especially because of the impossibility to access the U.S. market, the largest for the Caribbean area.

After the terrorist attack on the Twin Towers in New York City, the industry entered a much slower period of growth, to which decisions of domestic economic policy also contributed. Later came the 2008 international crisis, which severely affected most of the markets that were relevant to Cuba, especially Western Europe.

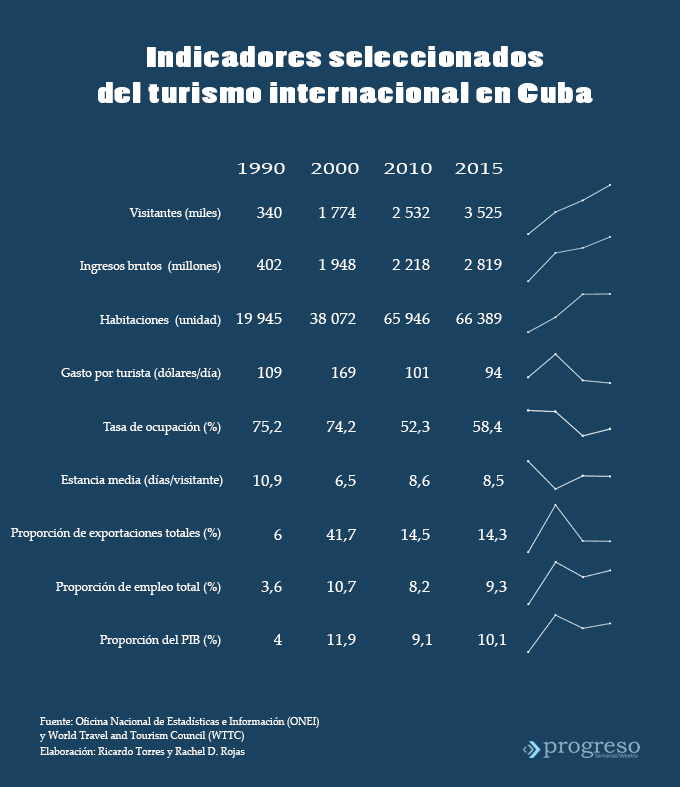

The announcements in December 2014 were the beginning of an unprecedented performance in modern history: in only two years, Cuba welcomed one million additional visitors and will close 2016 with a figure of about 4 million. The good news is that not only has the U.S. market boomed (for obvious reasons) but also increases have been observed in Cuba’s main qualifiers. The following graphic shows a summary of key indicators for the sector. (Visitors in thousands; Gross Income in millions; Rooms; Money spent per tourist; Rate of Occupancy; Median stay: days/visitor; Export Rate; Employment Rate; Share of GDP)

The first characteristic that can be extracted from these data is that the sector’s performance corresponds to a type of extensive growth, where the dynamics of revenue depend basically on the increase in arrivals. Beginning in 2000, we clearly see a decline in the deficiency indicators, such as expenditures by tourists and the occupancy level.

Between 2000 and 2010, the number of visitors rose faster than the revenue, with the occupancy showing an even greater dynamics. In the latest period (2010-2015), the first trend holds, as the net addition of new rooms stagnates.

The pattern described above is consistent with the predominant segment (sun and sand) and the model of business that accompanies it (all-inclusive). The combination of both is related to a highly standardized service, similar to a “commodity.” This means that competition is based essentially in the costs, which causes a lowering of the internal spillovers, prominently including the wages.

The drop in the average expenditures per visitor is related to several aspects. First, it is noticeable that this happens at the same time that the hotels have been shifting to four- and five-star installations, which would indicated greater costs, at least in lodging.

Secondly, it is consistent with the structure of tourist expenditure, which remains concentrated on lodging and (to a lesser degree) in gastronomy, but the offers that can add value and differentiation to the destination continue to be insufficient.

Anyway, the available data should be evaluated cautiously, especially in the most recent periods. The statistical system is probably incapable, for various reasons, of detecting a part of the expenditures made in the private and cooperative sectors. In July of this year, the Ministry of Tourism and the National Office of Statistics and Information (ONEI) announced that they would work in improving those methods.

In the present circumstances, it is evident that the supply is insufficient to cover the demand. The very characteristics of the Cuban tourist model imply that the bulk of the rooms are built in the sun-and-sand sites, while the renewed interest in Cuba is related to other attributes, such as the attractiveness of its cities, especially Havana.

With luck, it doesn’t seem that this scenario will change in the foreseeable future. On Aug. 31, JetBlue made its first scheduled flight to Cuba in more than 50 years. It is possible that flights to Havana will begin in November. The licenses already granted imply that the seats available for travel to the island will multiply by four.

Experts say that the demand remains firm, even within the 12 permitted categories. Cruise operations have also begun. This will bring extreme pressure upon the Cuban infrastructure, already hard pressed by the “boom” in recent years.

Cuba brings together unique attributes — such as its history, art and culture, its labor force, and low levels of crime — that would allow it to modify its tourism model mid-range. This would differentiate it significantly from the rest of its closest competitors.

This change would focus on an increase of the profit margins through a sophisticated and diverse product, with a world-class infrastructure and service to the customer.

The opening in the U.S. market can bring the volume necessary to make this transition feasible. It is also well known that the benefits from tourism activities depend on the characteristics of the receiving economy. This possibility cannot be conceived if isolated from the other necessary transformations.

Within a reasonable period, we can visualize at least three segments with a practically unlimited potential: creative industries, health, and nature. The strength and authenticity of Cuban culture make it a point of reference in the region and the world.

The fascination for these qualities has been demonstrated in the long list of representatives of fashion, the cinema, music, design, architecture and fine arts who have paraded through Havana in the past year. It is probably easier to film a Hollywood movie here than to stimulate the creation of Cuban filmmakers and the entire ecosystem that accompanies them.

Also well known is the prestige of medical care. Cuba has practically all components needed to become a world reference for health tourism: universities for all medical specialties, facilities, highly qualified personnel, unique treatments, prestige in numerous specialties, advanced research, manufacture of generics and biotechnological products, a climate suitable for recovery, and now the nearness of a market that could be its most important outlet.

However, ambition and courage are needed to implant a consistent strategy.

The value of Cuba’s nature gets less credit. The island has declared about 22 percent of its surface to be protected areas. Numerous locations provide spectacular beauty: Viñales has been named by UNESCO as a world cultural patrimony; others are Guanahacabibes, the Zapata Swamp, Cuchillas del Toa.

The archipelago has the world’s longest coral reef, mangrove swamps, tropical forests and numerous islands and keys with pristine waters that are ideal for diving. More promotion and an integral conception are needed to adequately exploit these treasures.

It is difficult to image how this could have been done differently in the early 1990s, due to the lack of experience, the dearth of resources and the market limitations imposed by the U.S. embargo. But now we must make a deep analysis of the model that is within our reach in the next several years.

This will likely require the emergency of many new enterprises, most of them probably of a private nature, that will become specialized suppliers to the sector. This would create better conditions for a repositioning within the value chain of tourism.

The dominant actors in such a scenario are the tour operators and foreign travel agencies and, to a lesser degree, the international hotel chains working with the airlines. Cuban companies have a very small presence in the leading positions, which results in a reduced proportion of the total value staying in this country. In our current model, the number of visitors is the indicator par excellence. And this is unsustainable.

A differentiated destination offers another value added. To change from a tourism of masses to a more selective and specialized tourism offers more chances of attracting the type of visitors who would be interested in enjoying cultural riches or nature instead of other offerings, such as sex or gambling, that don’t fit into the type of society we are trying to build.

International tourism has the potential to make a significant contribution to the country’s economic and social development. This is a crucial moment. Two very different roads lie before us. One will take us to little more than expanding the scale of the last 25 years. Instead of three million visitors, we’ll welcome five million or seven million people, among them many Americans. They will fill the international hotel chains, prominently those on our northern coast. With luck, they’ll occupy some spaces in the more lucrative segments.

However, there is an alternative that today seems almost like a dream. It is possible to create the area’s most diversified and differentiated destination, anchored in our history, culture, art, education, health and nature, in an alliance with the world’s most prominent actors in the industry. A more profitable model, with better jobs and many domestic actors at all levels. An unrepeatable mix that will protect our environment and our patrimony.

The table is set.

***

Ricardo Torres is a professor of economics and Cuban economy with the Center for the Study of the Cuban Economy at the University of Havana.