A cigar maker in Tampa

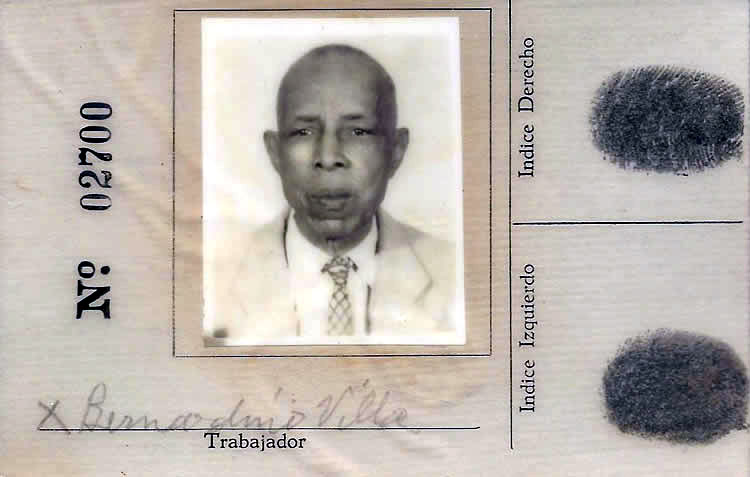

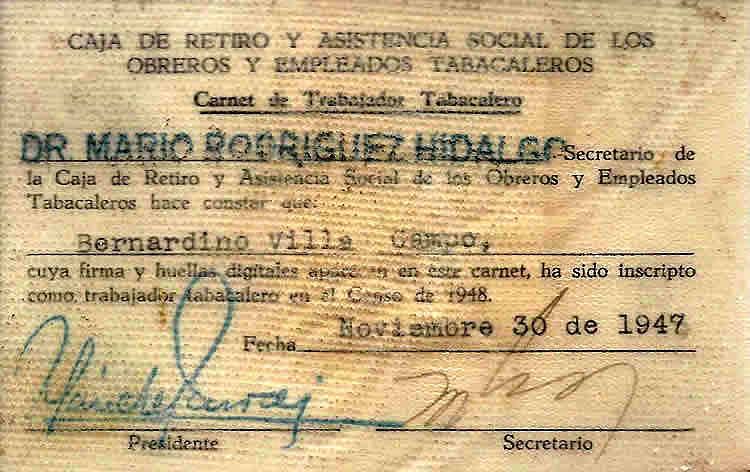

Bernardino Villa Campo. Black, medium height. He wore a straw hat, boots and light-colored shirts, always long-sleeved. Spoke English well, played the clarinet. “Villita,” was how his friends called him. Several of them visited him often to ask him for advice, because of his phlegmatic, deliberate demeanor. My grandmother, his daughter, remembers that he walked slowly and spoke softly.

He arrived in the United States like many other Cubans who settled in Jacksonville, Ocala, New Orleans, St. Augustine, Key West. About 1885, there were 4,527 Cubans in Key West, one third of the area’s 14,000 inhabitants, according to a contemporary census. Among them, Bernardino lived an ordinary life that can only be imagined. He, who never opined about politics, became part of a splendid zone of Cuban patriotism.

The cigar factories and clubs of South Florida incubated the so-called Gómez-Maceo Plan (1884) and the War of ’95. “They organize and prepare for the purpose of keeping alive the restlessness and mistrust in our Greater Antilles,” grumbled the Spanish consul in a letter to his foreign minister.

Was the old man (at the time a young man) a revolutionary? Or was he simply swept by the tide? “I imagine that, from the moment he emigrated, he felt something,” my grandmother surmised. A sign in a cigar factory owned by Eduardo Hidalgo Gato read: “Cubans: Whoever does not donate money for the cause of the revolution cannot work in this factory, which is the factory of a free Cuba.”

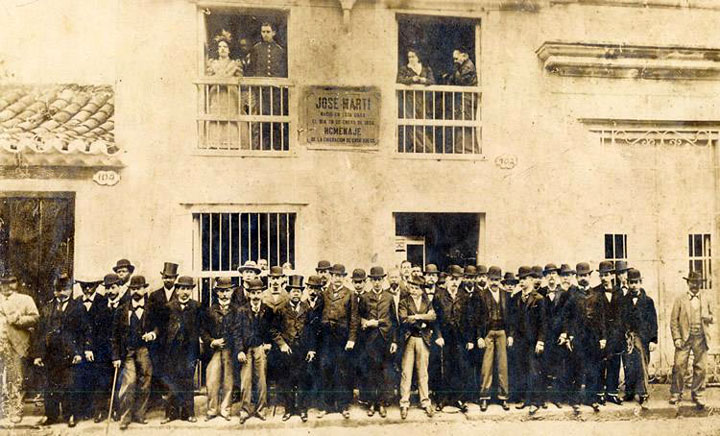

Martí arrived in Tampa on Nov. 25, 1891, invited by the émigrés. During those days, he toured factories and shops and delivered the speeches that later would become known as “With all and for the good of all,” and “The new pines.”

“He calls himself Cuban, and a sweetness like soft brotherhood spreads throughout our entrails, and our savings box opens, and we squeeze at the table to make room for one more!” José Dolores Poyo published his words in the newspaper Yara, which later was read in the cigar factories.

Maybe Bernardino was listening, among the eager multitude or from his work table. Maybe he left without making a comment; he was definitely a man of few words. For sure, he didn’t expect to be part of such a huge and definitive undertaking. It was a matter of doing what was right, what needed to be done.

One month later, Martí arrived in “El Cayo,” as the Cubans called it, aboard the ship Olivette, which later carried the famous cigar that contained the order to rise up. Contemporary reports describe an enthusiastic welcome.

Martí himself wrote in his newspaper, Patria: “Yesterday, in the Key West factory ‘The Spanish Rose,’ a fervent Cuban who was sick at home the week that the voluntary contribution was collected did not have enough money to donate a day’s wages for his homeland. But he borrowed it, so he could do his duty to give his children a nation where they can wish to live.”

Several clubs that were the foundation for the Cuban Revolutionary Party (PRC) restructured themselves as Masonic lodges and kept some rites and the secret nature of the brotherhood. “Villita” was a member of the Odd Fellows, which had emerged in the isle in 1883. Shortly after it was created, the colonial government banned it; only two clandestine cells remained active.

On April 10, 1892, 34 clubs approved the bases of the PRC: 13 in Key West, 7 in New York City, 5 in Tampa, 5 in Kingston, and one in Philadelphia, Boston, Ocala and New Orleans, respectively.

“The rich contributors of blood and money were — as happens in the times of great sacrifices for the good and glory of nations — rare exceptions. It could be said that the last life vest for the combatants was the cigar maker’s wallet,” wrote Máximo Gómez. And the fighting began.

From Tampa, troops departed toward the Spanish-Cuban-North American War. Did the old man see the Rough Riders board the ships? According to data, 30,000 men were at the ready, training. If he was there, he must have seen them. Did he know what was happening? Did he feel concern or fear?

Afterward, things changed. Upon returning, the émigrés founded the Cayo Hueso neighborhood in Central Havana. Bernardino lived on Concordia Street. There he remained, and the family history says that “the neighborhood was in an uproar when word got out that Conchita was marrying a Negro.” Abuela Mama, as she was called, was tall, had white skin and a waist whose width was inversely proportional to the width of her hips.

Four daughters were born: Edelmira, Emelina, Elena and María Teresa, beautiful and temperamental, who called themselves “the fiery mulattas.” There was a son, Bernardito, but he died at 20 because of a congenital hydrocephalus. Because “Villita” only had daughters, his surname ended with him.

“Bernardino never wanted to belong to that,” says my grandmother, quoting her grandmother. “That” means the associations formed by veterans, émigrés, or some such groups. Because he never belonged to them, Bernardino, never received the pension issued by the government. It would have served him well. During the days of Machado, Conchita lost the remains of her mother because she lacked 3 pesos to pay for a change of niche.

[Translator’s Note: When a cemetery niche was not fully paid for, the remains inside were thrown into a common grave.]

Ramón Guerra, museum keeper at the Martí Birthplace, says that the cigar makers “returned the Apostle to us,” his gospel, because at the time no printed works existed. “Martí was unknown in Cuba.” They were the first to look for the house and built the marker that’s there today. But Bernardino never wanted to belong “to that.”

From time to time, Bernardino sipped coffee and smoked a cigar. He never shouted or became flustered. His grandsons Gerardo and Carlos called him “Titico.” When they fled to the Malecón, he went out to find them. Carlos had a son who studied music and inherited the old clarinet.

Until he retired, Bernardino worked at the H. Uppman factory. My grandmother made the ribbons that he used to wrap the cigars with, and he gave her a few cents in return. If someone at the cigar factory asked him for ribbons, he said no, because they were made by his granddaughter. “I think he played in one of those small dance orchestras,” she recalls.

The day the old man signed his retirement papers, he went home and said: “I closed my career with a golden clasp.” Afterward, Villita devoted himself basically to be a good man.

Progreso Semanal/ Weekly authorizes the total or partial reproduction of the articles by our journalists, so long as source and author are identified.