CIA admits it was behind Iran’s coup

By Malcolm Byrne

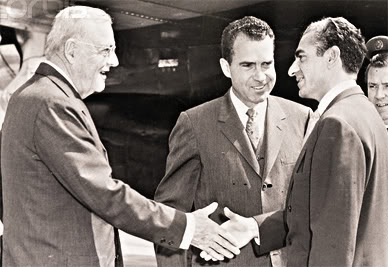

Sixty years ago this Monday, on August 19, 1953, modern Iranian history took a critical turn when a U.S.- and British-backed coup overthrew the country’s prime minister, Mohammed Mossadegh. The event’s reverberations have haunted its orchestrators over the years, contributing to the anti-Americanism that accompanied the Shah’s ouster in early 1979, and even influencing the Iranians who seized the U.S. Embassy in Tehran later that year.

But it has taken almost six decades for the U.S. intelligence community to acknowledge openly that it was behind the controversial overthrow. [The National Security Archive obtained the document proving the fact through the Freedom of Information Act.]

The document was first released in 1981, but with most of it excised, including all of Section III, entitled “Covert Action” – the part that describes the coup itself. Most of that section remains under wraps, but this new version does formally make public, for the first time that we know of, the fact of the agency’s participation: “[T]he military coup that overthrew Mosadeq and his National Front cabinet was carried out under CIA direction as an act of U.S. foreign policy,” the history reads. The risk of leaving Iran “open to Soviet aggression,” it adds, “compelled the United States … in planning and executing TPAJAX.”

TPAJAX was the CIA’s codename for the overthrow plot, which relied on local collaborators at every stage. It consisted of several steps: using propaganda to undermine Mossadegh politically, inducing the Shah to cooperate, bribing members of parliament, organizing the security forces, and ginning up public demonstrations. The initial attempt actually failed, but after a mad scramble the coup forces pulled themselves together and came through on their second try, on August 19.

Why the CIA finally chose to own up to its role is as unclear as some of the reasons it has held onto this information for so long. CIA and British operatives have written books and articles on the operation – notably Kermit Roosevelt, the agency’s chief overseer of the coup. Scholars have produced many more books, including several just in the past few years. Moreover, two American presidents (Clinton and Obama) have publicly acknowledged the U.S. role in the coup.

But U.S. government classifiers, especially in the intelligence community, often have a different view on these matters. They worry that disclosing “sources and methods” – even for operations decades in the past and involving age-old methods like propaganda – might help an adversary. They insist there is a world of difference between what becomes publicly known unofficially (through leaks, for example) and what the government formally acknowledges. (Somehow those presidential admissions of American involvement seem not to have counted.)

Finally, there is the priority of maintaining good relations with allies, particularly in the intelligence arena. British records from several years ago show that the Foreign Office (and presumably MI6, which helped plan and carry out the coup) has been anxious not to let slip any official word about its involvement. To outside observers, this subterfuge borders on the ludicrous given that Iranians have assumed London’s role for so long. Yet, by most indicators, the U.S. intelligence community has gone along, regardless of the consequences for Americans’ understanding of their own history.

The fact that the CIA has now chosen to shift direction, at least this far, is something to be welcomed. One can only hope it leads to similar decisions to open up the historical record on topics that still matter today.

(From Foreign Policy)