Child poverty up in more than half of developed world since 2008

Child poverty has increased in 23 countries in the developed world since the start of the global recession in 2008, potentially trapping a generation in a life of material deprivation and reduced prospects.

A report by Unicef says the number of children entering poverty during the recession is 2.6 million greater than the number who have been lifted out of it. “The longer these children remain trapped in the cycle of poverty, the harder it will be for them to escape,” it says in Children of Recession: the Impact of the Economic Crisis on Child Wellbeing in Rich Countries.

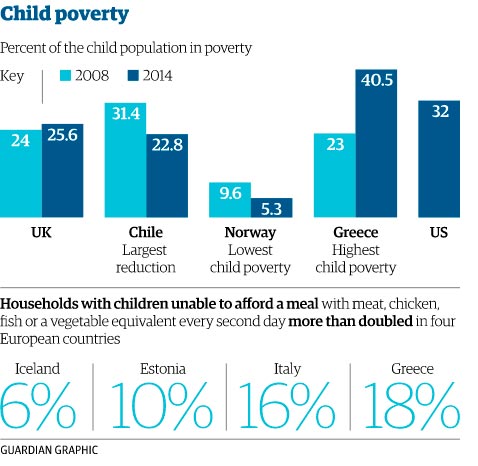

Greece and Iceland have seen the biggest percentage increases in child poverty since 2008, followed by Latvia, Croatia and Ireland. The proportion of children living in poverty in the UK has increased from 24% to 25.6%.

Eighteen of the 41 countries in the study have seen falls in child poverty, topped by Chile which has seen a reduction from 31.4% to 22.8%.

Norway has the lowest child poverty rate, at 5.3% (down from 9.6% in 2008), and Greece has the highest, at 40.5% (up from 23% in 2008). Latvia and Spain also have child poverty rates above 36%. In the US, the rate is 32%.

“In the past five years, rising numbers of children and their families have experienced difficulty in satisfying their most basic material and educational needs,” says the report. “Unemployment rates not seen since the Great Depression of the 1930s have left many families unable to provide the care, protection and opportunities to which children are entitled. Most importantly, the Great Recession is about to trap a generation of educated and capable youth in a limbo of unmet expectations and lasting vulnerability.”

It adds: “The impact of the recession on children, in particular, will be felt long after the recession itself is declared to be over.”

The study’s authors asked people about their experiences and perceptions of deprivation, based on four indicators: not having enough money to buy food for themselves or their family; stress levels; overall life satisfaction; and whether children have the opportunity to learn and grow.

In 18 of the 41 countries, scores showed a worsening situation between 2007 and 2013, revealing “rising feelings of insecurity and stress”.

The percentage of households with children unable to afford a meal with meat, chicken, fish or a vegetable equivalent every second day more than doubled in four European countries – Estonia (to 10%), Greece (18%), Iceland (6%) and Italy (16%).

Material deprivation and stress affected parents’ relationships with their children, the report for the UN’s agency found. “Lower levels of consumer confidence are associated with increased levels of high-frequency spanking, a parenting behaviour that is associated with greater likelihood of being contacted by child protective services.”

Young adults have arguably been the hardest hit by the recession, according to the report, with 7.5 million within the EU not in education, employment or training (Neet) – nearly a million more than in 2008.

Israel had the highest Neet rate, with 30.7%, but this was a marginal increase on 2008. The biggest absolute increases were in Croatia, Cyprus, Greece, Italy and Romania. In contrast, Turkey’s Neet rate fell from 37% in 2008 to 25.5% in 2013 – still the second-highest rate.

“Even when unemployment or inactivity decreases, that does not mean that young people are finding stable, reasonably paid jobs. The number of 15- to 24-year-olds in part-time work or who are underemployed has tripled on average in countries more exposed to the recession,” the report says.

Many countries responded to the recession by adopting economic stimulus packages and pushing up public spending, it points out. “Governments that bolstered existing public institutions and programmes helped to buffer countless children from the crisis – a strategy others may consider adopting.”

The report concludes: “The problems have not ended for children and their families, and it may well take years for many of them to return to pre-crisis levels of wellbeing. Failing to respond boldly could pose long-term risks.”

(From the: The Guardian)