Breaking the Iran nuclear deal means trouble for the U.S.

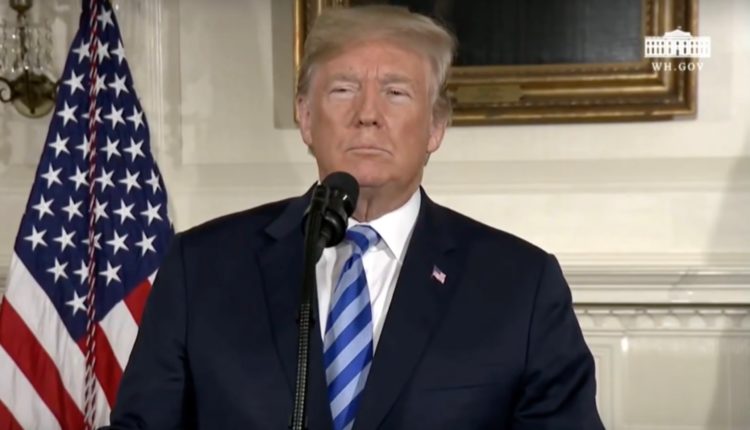

Tuesday (May 8), President Donald Trump announced that the United States will withdraw from the nuclear international agreement under which Iran agreed to halt its nuclear program. The international inspectors responsible for ensuring Iranian compliance, the U.S. intelligence agencies, and the other big powers that were party to the agreement all say the Iranians have been complying. So why would the United States, which under Barack Obama was key to crafting the deal, walk away?

Donald Trump. Trump has been braying about the agreement since the campaign, calling it worst deal ever, promising to tear it up as soon as he got into power. But there was a small stumbling block. The entire world (except Israel and, in a low-profile way, Saudi Arabia) opposed the move, as did Trump’s initial national security team. Trump fired the dissenters—Tillerson, the Secretary of State; McMaster, the National Security Adviser—axed, as is Trump’s habit, in a cruel and humiliating way. [Trump’s reality show, the Apprentice, was successful because it was real, authentic: Trump wasn’t playacting; he delights in the power to control the fate of subordinates and to use it to crush and humble them.]

McMaster and Tillerson just weren’t singing in harmony with the boss. Trump replaced one with a jackass (John Bolton), who can bray like the Commander-in-Chief, and the other with another ultra-hardliner, albeit a smoother one (Mike Pompeo).

These domestic bully boys were joined by one of the biggest stars of the international bully boy circuit, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, who rivals Bolton in abrasiveness. Now Trump had assembled his support group, a minuscule but like-minded one. But this time Trump couldn’t even count with the backing of Vladimir Putin, another bully boy in the international league, who supported the Iran nuclear deal, much less with this country’s closest allies — Germany, France and the UK — whose leaders lobbied hard to no avail to convince Trump not to walk away.

Demagoguery aside, Trump and the other members of the gang of four really believe the Iran nuclear deal is a bad one. Trump’s idea of a good deal is one negotiated at the point of a gun, the kind of deal the United States imposed to steal Guantanamo from Cuba and the Southwest from Mexico. The sort of deal Putin made in taking Crimea from Ukraine. The kind of deal Netanyahu makes every day when he steals Palestinian land. What they want, in other words, is no deal at all, only unilateral concessions obtained through various forms of coercion, including violence.

The problem for the gang of four is that you don’t get that kind of “deal” without having plenty of boots on the ground—consider the examples just cited. Trump instead has talked about his desire to reduce the number of U.S. troops in Syria and even in South Korea. And the American people will not abide yet another war.

The administration thinks it can coerce Iran by making it bleed economically through renewed sanctions. This strategy doesn’t work when leaders have unchallenged control, strong political will and enough people behind them unwilling to deal on bended knees. Witness Cuba.

More likely than an Iranian cave-in is an increase in the influence of the hardliner in Iran. They opposed the deal from the beginning. They said that any agreement with the United States is a fool’s errand. Trump has made them look like geniuses or seers.

The hardliners, who want Iran to walk away from the agreement, don’t control Iran right now. The government is vowing to continue to observe the terms of the deal unless the Europeans join the Americans in re-imposing economic sanctions. Which is exactly what the Trump administration will try to do by enforcing a law that bars Americans firms from doing business with foreign companies who do business with Iran.

The Trump administration hopes that if the United States succeeds in getting the Europeans to join in isolating Iran economically, the resulting pain in a country already mired in economic troubles will motivate the Iranian people to revolt and overthrow their government. A more likely outcome is that the Iranian people, feeling besieged, will rally around their leaders and that hardliners will get more power in the government. This, in turn, could lead to a change in Iranian policy and a return to the nuclear program.

Even if the Iranian government chooses to forego that route for now, Iran has many tools it can use to make life for the United States more uncomfortable in the region and in the homeland itself. Iran is in de facto control of Iraq and can make more trouble for the United States there. The Iranians could step up their support for the Houthis in Yemen, a country long-enduring a brutal air assault by Saudi Arabia with the full support of the United States.

After walking away from the Paris climate accord, this latest break by Trump from the consensus among the world’s advanced democracies will isolate the United States from its allies even more. And, in moving the U.S. embassy in Israel to the contested city of Jerusalem, Trump succeeds in angering many Arab governments, including U.S. allies.

The self-isolator in chief strikes again.